Peter Singer On the Life You Can (and Should) Save

Whose responsibility is it to improve society? With his famous thought experiment of the drowning child, the philosopher Peter Singer argues we each have a more urgent duty than we might think…

Whose responsibility is it to improve society? Do we each have a moral duty to help those we don’t know? And, if so, how far does that duty go?

In his 2009 book The Life You Can Save, the philosopher Peter Singer offers his own highly-influential answers to these questions, beginning with the following famous thought experiment (which, due to its canonicality, is worth presenting in full):

On your way to work, you pass a small pond. On hot days, children sometimes play in the pond, which is only about knee-deep. The weather’s cool today, though, and the hour is early, so you are surprised to see a child splashing about in the pond.

As you get closer, you see that it is a very young child, just a toddler, who is flailing about, unable to stay upright or walk out of the pond. You look for the parents or babysitter, but there is no one else around. The child is unable to keep her head above the water for more than a few seconds at a time. If you don’t wade in and pull her out, she seems likely to drown.

Wading in is easy and safe, but you will ruin the new shoes you bought only a few days ago, and get your suit wet and muddy. By the time you hand the child over to someone responsible for her, and change your clothes, you’ll be late for work. What should you do?

Our response in this situation, thinks Singer, is surely unquestionable: we should wade in and rescue the child.

Who cares about dirtying their clothes or being late for work when a child’s life is at stake? Not wading in is surely monstrous here: inaction is morally reprehensible.

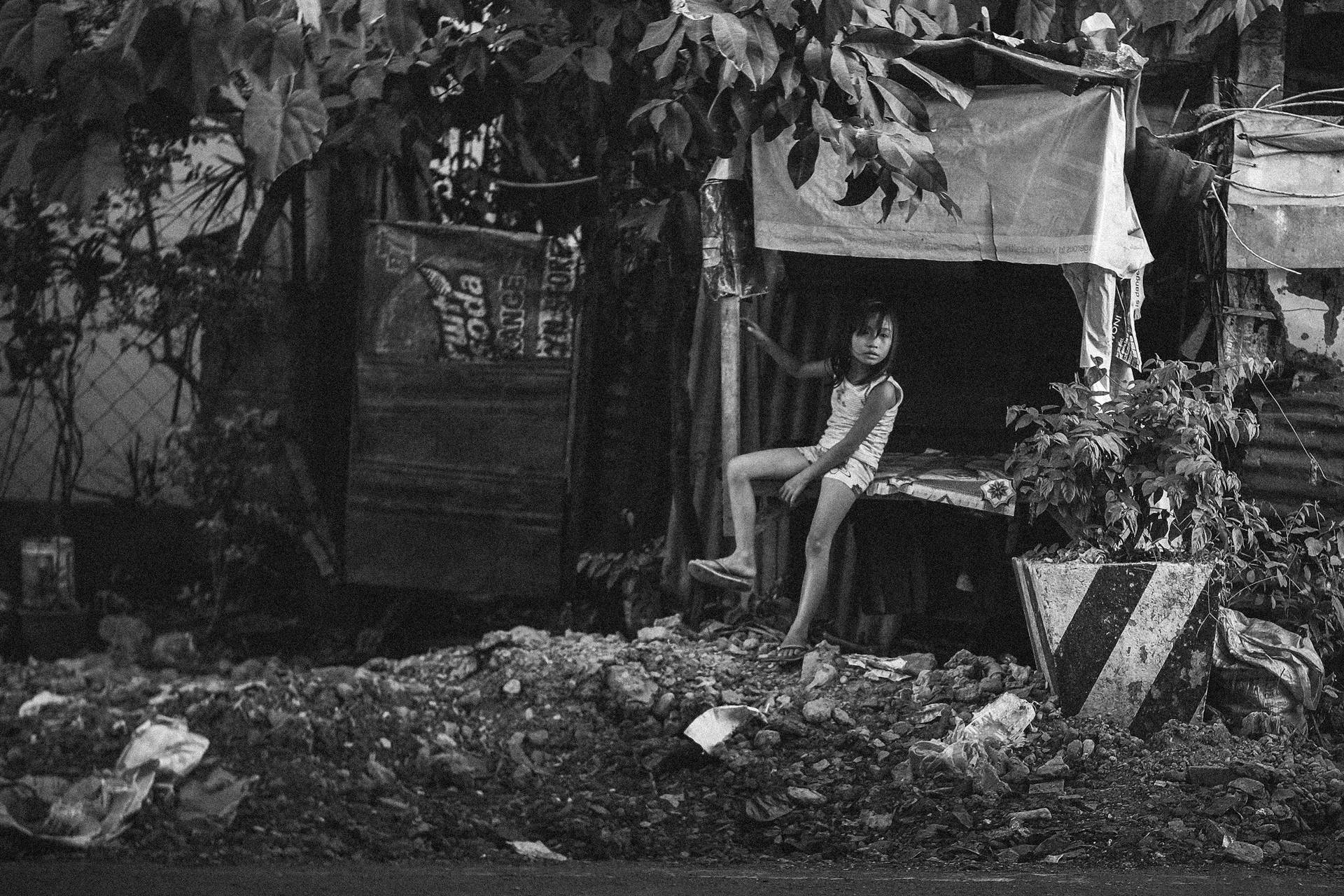

Having established this, Singer then asks us to consider the fact that, actually, there are children dying of preventable causes around the world every single day.

In poverty-stricken areas of the globe, for instance, children lack access to life-saving medicines or vaccinations that cost just tens of dollars to administer.

If we’re willing to sacrifice our clothes to save the life of a child drowning in front of us, then surely we’d be willing to sacrifice a few spare dollars to save children elsewhere from preventable deaths.

The question Singer then puts to us is: well, why don’t we? Why aren’t we all routinely giving as much as we can to help save children’s lives?

Of course, we all need money to survive. We might think, “I wish I could do more, but I need to achieve financial security in my own life first.”

But Singer’s basic insight is that, if you live in an affluent country on a lower-middle-class income or more, you have access to resources that people living in poverty may never see in their lifetimes.

Though we may feel we don’t have enough, people living in poverty actually don’t have enough.

This is not to deny people in affluent countries face genuine difficulties, but the 700 million people living in extreme poverty (i.e. on less than $2.15 a day) suffer daily hardships tied to the most basic of human necessities — like access to food, shelter, clean water, and healthcare.

So, why might we still feel unsure about giving our resources away..?

Proximity, the diffusion of responsibility, and the inefficiency of giving

One thing that might stop us from enthusiastically donating spare resources right away is proximity. Perhaps we feel that a child drowning in front of us is just an entirely different case to the preventable deaths of children elsewhere. We can physically wade in and rescue the child in front of us; the children elsewhere are out of reach.

But Singer pushes back on this point. Why is our geographical location morally relevant? A child’s life ‘over there’ is worth just as much as a child’s life ‘over here’: the morally relevant point is that it’s within our power to save that life — and, through inaction, we are choosing not to.

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox:

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

Another objection we might raise is that there is an issue about responsibility here. For the child in front of us, there is no one else around to rescue them. If we do nothing, the child dies, and the responsibility is ours alone.

However, with children elsewhere, it’s not just us who could rescue them — anyone could. The level of responsibility we have is surely diffused by this.

Again, Singer pushes back on this. Morally, the number of people who could help is of no relevance; the relevant point is that we are deciding not to.

Perhaps we feel this is unfair — we might think Singer is attacking us personally, when we’ve done absolutely nothing to create the terrible conditions in the world.

The Canadian philosopher Jan Narveson would agree. In his essay We Don’t Owe Them a Thing!, he wonders why we have a responsibility to help those we haven’t harmed:

We are certainly responsible for evils we inflict on others, no matter where, and we owe those people compensation… Nevertheless, I have seen no plausible argument that we owe something, as a matter of general duty, to those to whom we have done nothing wrong.

But this, Singer responds, represents a rather callous moral position, and maintaining it would mean throwing out all forms of welfare and social aid.

If people suffer from a natural disaster, for instance, is it morally acceptable to simply stand by and forsake them? “Oh, an earthquake destroyed their city and trapped some of them under rubble. Too bad…”

Moreover, if we consider the fact that we live in a global system that benefits affluent countries, we might recognize a responsibility to people in poverty-stricken parts of the globe on Narveson’s own terms: we have caused such people harm, and owe them compensation.

We may not be personally blameworthy for the power structures that have colonized and exploited other nations throughout history, but as participating members of human civilization we can certainly acknowledge and take responsibility for those structures.

Feeling our objections to be on shaky ground, we might as a last resort point to the inefficiency of charitable giving. “I’d love to give more, but the charities waste all the money on administrative costs! Barely anything goes to the actual cause! Besides, governments around the globe are corrupt! What I give won’t make the slightest difference to all the problems people face!”

Singer acknowledges that some charities can be inefficient, and that corruption is a problem; but he has actually spearheaded a solution to this himself by creating a website (thelifeyoucansave.org) that ranks various organizations by their effectiveness. Donors can track exactly where their money goes, and view exactly what impacts they’ve made.

How much are we supposed to give?

Suppose we are persuaded by Singer’s arguments thus far. We might then wonder: well, how much are we supposed to give? If I’ve worked hard to secure resources for myself and my loved ones, how much am I obliged to part with to improve the lives of people I don’t know?

Singer’s moral answer is that we should give as much as we can without imposing unnecessary hardship on ourselves.

Many push back on this, however, claiming it is unreasonably demanding and unrealistic to expect people to part with the majority of their hard-earned resources.

Accordingly, Singer’s practical, ‘public-facing’ answer is that we pledge a small proportion of our post-tax incomes.

10% is a popular figure, but Singer actually offers an income-adjusted chart that recommends the proportion we should give depending on how much we earn, and it can be as low as 1%.

By keeping the demands reasonable in this way — i.e. by allowing people to generally maintain their lifestyles rather than impose hardship on themselves — Singer recognizes that more people are likely to pledge, and more money will be raised to do good.

On this view, then, Singer isn’t saying we should necessarily feel guilty for occasionally treating ourselves or our loved ones rather than donating every spare resource we have to a worthy cause.

As a ‘utilitarian’ effective altruist, Singer says what’s right is whatever leads to the most good.

And, if occasionally treating ourselves makes us happy, and our happiness sustains our ability to consistently generate resources, and this consistency allows us to pledge a percentage of our monthly income, then occasionally treating ourselves is fine, for it enables us to commit to routine donations that we might not otherwise make.

As Singer writes:

An ethical approach to life does not forbid having fun or enjoying food and wine; but it changes our sense of priorities. The effort and expense put into fashion, the endless search for more and more refined gastronomic pleasures, the added expense that marks out the luxury-car market — all these become disproportionate to people who can shift perspective long enough to put themselves in the position of others affected by their actions.

What do you make of Singer’s arguments?

Singer’s arguments have been deeply influential in applied ethics, particularly with regards to what philosophers call the principle of beneficence — i.e. the extent to which we should help those in need.

While Singer suggests we have strong moral obligations to be beneficent, some philosophers find his position far too demanding and disruptive.

What do you think?

- Do you find Singer’s thought experiment of the drowning child persuasive?

- Do you think Singer’s arguments addressing proximity, the diffusion of responsibility, and the inefficiency of giving are convincing?

- To what extent should we disrupt our own lives and projects to help those less fortunate than ourselves?

- Is Singer’s moral philosophy too demanding?

- Or, as some defenders of Singer claim, does it feel demanding simply because it represents moral progress, and in a few centuries humans will wonder, aghast, at how affluent people stood by while people died from extreme poverty?

- Is the most effective way to be beneficent simply to give the right organizations more resources? What else can we do?

- Whose responsibility is it to improve society?

Learn more about Effective Altruism and other philosophical approaches to the good life

This article is an adapted extract from the ‘Effective Altruism’ chapter of my introductory philosophy course, How to Live a Good Life. If you found it interesting, consider signing up to the full course to join me and 300+ others in Philosophy Break Academy exploring and discussing Stoicism, Existentialism, Buddhism, Effective Altruism, and three additional philosophies for life.

You might also enjoy the following related reads:

- The Greatest Happiness of the Greatest Number: What Bentham Really Meant

- The ‘Golden Mean’: Aristotle’s Guide to Living Excellently

- Confucius: Rituals Grind Our Characters Like Pieces of Jade

- Epicureanism Defined: Philosophy is a Form of Therapy

- The 4 Cardinal Virtues: Stoicism’s Roadmap to the Best Life Possible

- Nozick’s Experience Machine vs. Hedonism: Should You Plug In?

Finally, if you enjoyed this article, you might like my free Sunday breakdown. I distill one piece of wisdom from philosophy each week; you get the summary delivered straight to your email inbox, and are invited to share your view. Consider joining 11,500+ subscribers and signing up below:

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 11,500+ subscribers enjoying my free Sunday Breakdown

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox.

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

About the Author

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 11,500+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (50+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Take Another Break

Each break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your philosophical curiosity.