Aristotle On Why Leisure Defines Us More than Work

Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle believed we could fulfill our potential less through our work, and more through our leisure activities.

In both his Nicomachean Ethics and his Politics, the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle writes extensively on the importance of leisure. Specifically, he argues that when it comes to living well, the quality of our leisure matters more than our work. People are apt to waste their leisure time, however, because they haven’t been educated in how to spend it constructively.

Aristotle writes that Sparta, for instance, never flourishes in times of peace because its constitution only trains the Spartans well for combat: it “has not educated them to be able to live in idleness.”

If we transpose Aristotle’s thought — that we often do not know how to spend our leisure time constructively — to the modern day, at one extreme we can find workaholism, where people let their work absolutely define meaning in their lives. Their leisure time is simply eaten away by more work, or by thinking about work.

At the other extreme, we find those who want to forget work so thoroughly they spend all their leisure time distracting themselves with physical pleasures or meaningless entertainment.

And, unfortunately, in the middle of these extremes lies perpetual anxiety: guilt for not being more ‘productive’; guilt for not being more ‘fun’ or ‘social’.

While there are a lucky few who are able to derive genuine fulfillment and personal growth from work, many unhappily find themselves somewhere on the spectrum between pointless workaholism and unconstructive recovery.

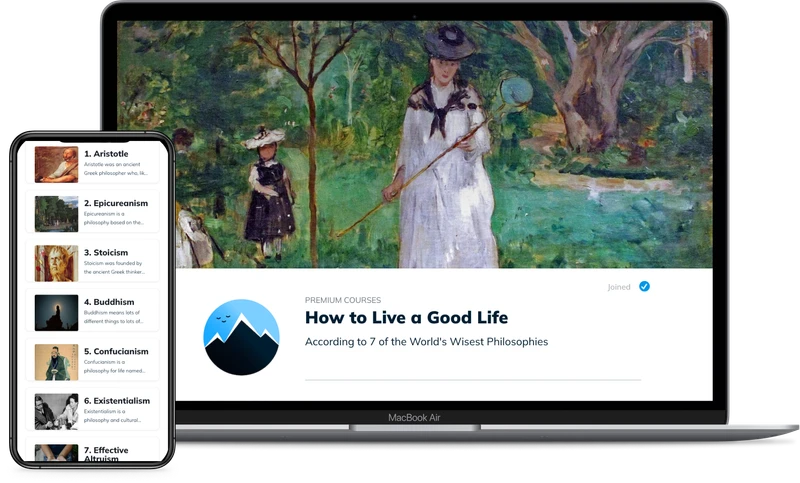

How to Live a Good Life (According to 7 of the World’s Wisest Philosophies)

Explore and compare the wisdom of Stoicism, Existentialism, Buddhism and beyond to forever enrich your personal philosophy.

Get Instant Access★★★★★ (100+ reviews for our courses)

Turning again to Aristotle, we find the solution lies in not viewing work or recovery as ends in themselves. Rather, they should be viewed merely as the means by which to further constructive leisure.

For it is in leisure, not in work or recovery, that the true beauty and meaning of the human condition can be found. Amusements and distractions have their place, but they do not constitute true leisure. In The Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle writes:

Amusements are more to be used when one is at work, for one who exerts himself needs relaxation, and relaxation is the end [goal] of amusement, and work is accompanied by toil and strain… we should be careful to use amusement at the right time, dispensing it as a remedy to the ills of work.

Work, of course, is a financial necessity, and for the overworked and underpaid, emphasizing leisure may be regarded as hopelessly privileged.

But, as Edith Hall notes in her book Aristotle’s Way, Aristotle believes it is only in our leisure time that the full human potential can be realized. Work should not carry the status that it does. Hall writes:

The objective of work is usually to sustain our lives biologically, an objective we share with other animals. But the objective of leisure can and should be to sustain other aspects of our lives which make us uniquely human: our souls, our minds, our personal and civic relationships. Leisure is therefore wasted if we do not use it purposively.

We should look at our spare time, then, not as ‘spare’, but as the most important time we have. With practice, we can (and should, Aristotle urges) structure our leisure to nurture the talents, tastes, and relationships that elevate us beyond the destructive work / recovery from work cycle, and that fulfill our potential as beings.

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox:

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

Perhaps in time, when someone asks us what we ‘do’, we can begin to define ourselves not by a career, but by our leisure activities. Our work need not ― and should not ― be the whole story.

Indeed, as 20th-century philosopher Hannah Arendt also argues in her discussion of how meaning is being replaced by productivity, the more we conceive ourselves primarily as ‘workers’, the more we will treat our own lives (and those of others) from a merely instrumental point of view. If we want to find more fulfillment in life, we need to create room for other conceptions of what it means to be human.

Ultimately, however, this is easier said than done, for the responsibility lies not just with us as individuals, but with the societies in which we live. If the goal is to live well the Aristotelian way, constructive leisure must be a realistic proposition for all citizens.

As the 20th-century philosopher Harry Overstreet put it:

Recreation is not a secondary concern for a democracy. It is a primary concern, for the kind of recreation a people make for themselves determines the kind of people they become and the kind of society they build.

Further reading

What do you make of Aristotle’s analysis? Do you prioritize leisure over work? If you’re looking to delve deeper into his teachings, you might enjoy our article on the ‘golden mean’, Aristotle’s guide to living excellently, as well as our explainer on how Aristotle distinguished between 3 levels of friendship. We’ve also created a reading list of the best books on and by Aristotle.

Get one famous philosophical idea in your inbox each Sunday

If you enjoyed this article, you might like my free Sunday breakdown. I distill one piece of wisdom from philosophy each week; you get the summary delivered straight to your email inbox, and are invited to share your view. Consider joining 25,000+ subscribers and signing up below:

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying my free Sunday Breakdown

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox.

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

About the Author

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (100+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Take Another Break

Each break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your philosophical curiosity.