What is Philosophy? Definition, How it Works, and 4 Core Branches

Your quick guide to exactly what philosophy is, how philosophers make progress, as well as the subject’s four core branches.

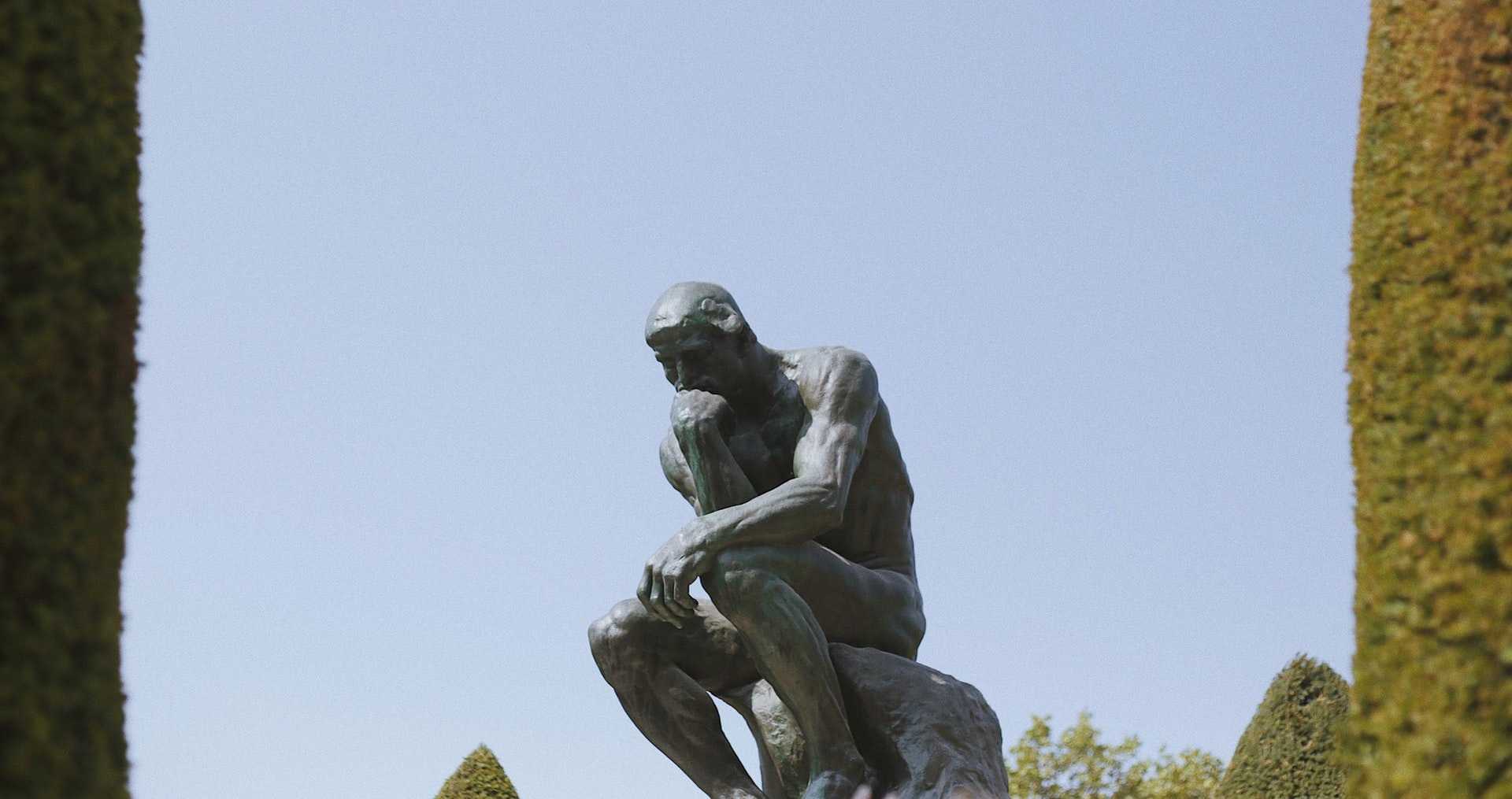

Why are we here, and what are our lives for? Why does anything exist, and why does it exist as it does? Is there a ‘right’ way to spend existence, or are all standards of right and wrong relative?

Such questions typically lurk in the background of our day-to-day lives. We may remember dwelling on them more attentively in childhood — for children are life’s most serious philosophers — and asking an endless chain of ‘whys’ after every inadequate explanation an adult offered. But as life and responsibilities began to get in the way, the questions may have started to fade…

But then along comes a book, a song, or a life event that brings all the questions roaring back: what is life about? What is it all for?

And it’s in this fertile territory that our inner philosophers roam, for philosophy doesn’t neglect the seemingly unanswerable, background questions of existence, but wrestles them — kicking and screaming — into the foreground.

Philosophy is essentially about recapturing and channeling the existential curiosity that comes so naturally in childhood, and formalizing it into a full-blown subject of inquiry.

What does philosophy mean?

The word ‘philosophy’ literally means ‘love of wisdom’, and this etymology is apt, for as a subject philosophy generally refers to the study of deep, fundamental questions (like those we opened with) relating to core aspects of the human condition. These questions typically revolve around the nature of existence, knowledge, consciousness, ethics, society, language, and more.

Facing up to such questions has been a central part of the intellectual histories of civilizations the world over. Here are some more:

What is the fundamental nature of reality? Why are we here? What happens when we die? What is the relationship between my mind and the world? How and why does consciousness arise? Do we have free will? Why is language meaningful? What’s the right thing to do? What does a just society look like?

Philosophical contemplation may not always provide final answers, but it can make it easier to live authentically in the face of the questions.

Beyond the study of such fundamental questions, philosophy can be defined more broadly as an act.

To philosophize means adopting a critical stance and using reason to draw logical conclusions. Be it deciding who to vote for or what to have for dinner, whenever we engage in critical thinking — whenever we rationally weigh up arguments — we engage in philosophy.

If we philosophize about our everyday concerns long enough, stripping them down to their core, we get closer to the questions that have occupied the great philosophers throughout history.

‘Who should I vote for?’ becomes ‘what does a just society look like?’; ‘what should I have for dinner?’ becomes ‘what’s the right thing to do?’; boredom or feeling unfulfilled can lead to ‘how can I establish meaning?’ and, if you’re not careful, simply staring at patterns of light on a wall can lead to ‘what is the fundamental nature of reality?’, or ‘is the world around me even real?’ — or, more starkly, ‘why does anything exist?’

Philosophy, then, is the proactive examination of the shifting tectonic plates upon which our thoughts and beliefs are constructed. It’s burrowing beyond the surface world of the everyday to question what, how, and why — to confront ourselves and reality at their most basic, general levels.

As American philosopher Wilfred Sellars simply puts it:

The aim of philosophy is to understand how things in the broadest possible sense of the term hang together in the broadest possible sense of the term.

How is philosophy done?

Considering such difficult, fuzzy subject matter, we might wonder how philosophers get anything done. How does philosophy make progress? How do philosophers decide what’s accurate and inaccurate?

Well, it essentially comes down to thinking hard about thinking, and separating out the sound thinking from the erroneous thinking. As the philosopher Thomas Nagel puts it in his book, What Does It All Mean?:

Philosophy is different from science and from mathematics. Unlike science it doesn’t rely on experiments or observation, but only on thought. And unlike mathematics it has no formal methods of proof. It is done just by asking questions, arguing, trying out ideas and thinking of possible arguments against them, and wondering how our concepts really work.

The philosopher Simon Blackburn agrees, describing philosophy in his book Think as conceptual engineering. Just as the engineer studies the structure of material things, so the philosopher — through careful and imaginative thinking — studies the structure of thought. Blackburn writes:

Understanding the structure involves seeing how parts function and how they interconnect. It means knowing what would happen for better or worse if changes were made. This is what we aim at when we investigate the structures that shape our view of the world. Our concepts or ideas form the mental housing in which we live. We may end up proud of the structures we have built. Or we may believe that they need dismantling and starting afresh.

Our ideas and concepts are the lenses through which we see the world, and as Blackburn puts it, “in philosophy the lens is itself the topic of study.”

How can we think clearly about thinking?

In order to separate good thinking from bad thinking, philosophy essentially runs on what philosophers call ‘arguments’, i.e. chains of reasoning that support certain conclusions.

There are a whole host of ways in which arguments can be presented and structured. They can be informal, like persuading a friend to go to a certain restaurant, or a politician arguing for a particular policy; or they can be formalized, whereby individual premises are clearly and logically presented to support a specific conclusion.

Judging the truth of an argument usually comes down to two things: the validity of its form, and the soundness of its premises. For example, consider the following formalized argument:

Premise 1: All humans are mortal.

Premise 2: Simone de Beauvoir is a human.

Conclusion: Therefore, Simone de Beauvoir is mortal.

This argument is ‘valid’ in that its form (in this case a syllogism, a type of deductive reasoning) is of satisfactory structure: the conclusion naturally ‘follows’ from the premises.

Moreover, the argument is ‘sound’ in that, not only is its form valid, but its premises are both true. If a valid argument has true premises, then its conclusion must be true. The argument above, concluding that Simone de Beauvoir is mortal, is thus an effective one.

Philosophers spend a lot of time analyzing arguments, inspecting them for so-called ‘fallacies’ i.e. faulty or unsound reasoning.

A logical fallacy that politicians are often guilty of, for instance, is a form of ad hominem (Latin for ‘to the person’), whereby the speaker attacks the character or motive of the person making an argument, rather than the premises or structure of the argument itself, in order to undermine the person’s conclusion.

Given arguments are often cloaked in this kind of persuasive and emotive rhetoric, philosophers must be on guard to get to the core of what someone putting forward an argument or counterargument is really saying, and to see whether the structure of their argument is valid, or their premises sound.

So, philosophy just rests on ‘arguments’?

Compared to the grand instruments of modern science, the humble arguments of philosophers may not seem a very impressive toolkit. But, when you think about it, it is upon such deployments of reason that all human knowledge is built.

The ability to formulate and respond to rational arguments is — arguably — among humanity’s most powerful intellectual abilities. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle, for instance, believed it is our sensitivity to reason that separates us from other animals, famously describing humanity as ‘the rational animal’.

What’s more, the philosopher David Chalmers in his book Reality+ suggests general philosophical inquiry is a precursor to the birth of more specialized disciplines: before the creation of any new specific field, philosophical curiosity and probing usually comes first.

Isaac Newton, for instance, considered himself a philosopher, and worked on philosophical questions about space and time. He made considerable progress in answering these questions, and as a result a new science of physics emerged. Chalmers argues something similar happened with economics, sociology, psychology, modern logic, formal semantics, and more: “All were founded or cofounded by philosophers who got clear enough on some central questions to help spin off a new discipline.” Chalmers continues:

In effect, philosophy is an incubator for other disciplines. When philosophers figure out a method for rigorously addressing a philosophical question, we spin that method off and call it a new field.

And, because philosophy has been so successful over the centuries at spawning new specialized fields, Chalmers notes that “what’s now left in philosophy is a basket of hard questions that people are still figuring out. That’s why philosophers disagree as much as they do.”

The 4 core branches of philosophy

While philosophical inquiry can be (and has been) applied to virtually any subject, one traditional picture organizes philosophy into four core branches. These are the branches of epistemology (the study of knowledge), metaphysics (the study of reality), value theory (the study of ethics and values), and logic (the study of correct reasoning).

The picture can be formulated differently. The branch of value theory, for instance, could be split into separate branches of aesthetics (the study of beauty) and ethics (the study of morality). Alternatively, instead of branches, topics could be listed as several instances of ‘Philosophy of X’, like ‘Philosophy of Mind’, ‘Philosophy of Language’, ‘Philosophy of Science’, ‘Political Philosophy’, and so on.

However, the four core branches of epistemology, metaphysics, value theory, and logic offer a fairly good representation of what philosophers are mostly concerned with. Here are some typical questions that sit within each branch:

1. Epistemology, the study of knowledge: What is knowledge? What makes knowledge possible? Are we born with innate knowledge, or is knowledge only acquired through sensory experience? Is the world around us ‘real’, i.e. is perception reality? Are our experiences of the world trustworthy? Is the potential of human knowledge unlimited? Or is it curtailed by our sensory apparatus and brainpower? (To learn more about these questions, view our epistemology reading list).

2. Metaphysics, the study of reality: What is the fundamental nature of reality? What is time? What is space? Is there a God? Do numbers exist? What makes a person a person? What is causation, and can there be such a thing as a ‘first cause’? Do we have free will? Why is reality like it is? What is consciousness? What does it mean for something to exist? Why does anything exist? (To learn more about these questions, view our metaphysics reading list, as well as our explainer on what metaphysics is).

3. Value Theory, the study of ethics and values: What is good? What is bad? Is it ever permissible to tell a lie, to steal something, to intentionally hurt or even kill someone? If not, why not? What’s the right thing to do, and what makes it right? What do we owe to each other as humans? What do we owe to non-human life? What’s the justification for any moral belief, and where do morals come from? What is beauty? Is it in the eye of the beholder, or are there objective standards for aesthetic quality? (To learn more about the questions on ethics, view our ethics and morality reading list).

4. Logic, the study of correct reasoning: How do you prove that a model of logic is correct? How do you prove that a logical proof is correct? How did nature produce logic? Is logical reasoning the best kind of reasoning everywhere in the universe? Can language be reduced to logic, and is the language of logic coherent? (To learn more about how logic relates to language, view our philosophy of language reading list).

Who does philosophy?

As we’ve seen, the concerns of philosophy are both deep and wide-ranging. There may be some areas that interest you, there may be others you find a little dry* (*cough, logic, cough).

Either way, philosophers have been studying the difficult questions mentioned above for thousands of years. The ancient Greek philosophers Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle are the major foundational figures of so-called ‘Western’ philosophy — so much so that, as the 20th-century philosopher Alfred North Whitehead once noted, “the safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists merely as a series of footnotes to Plato.”

‘Eastern’ philosophy, meanwhile, includes the traditions of thinkers from China, India, Japan, Persia, and more; while ‘African’ philosophy comprises the long and storied tradition of philosophy on the African continent.

The various traditions of philosophy have different styles, and within the traditions there are myriad branches and movements, making any kind of categorization very limited in its usefulness.

The key point is that anyone who thinks hard about the human condition, anyone who seeks to increase the accuracy of their thinking, anyone curious about why we are here and what our lives are for — any such person can be said to be doing philosophy. And some people throughout history have been especially brilliant at doing it, and have thus been raised to the status of ‘great philosophers’.

From the aforementioned ancient Greeks Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, as well as the Stoics and ancient Chinese philosophers like Laozi and Confucius, to the great North African philosopher Saint Augustine, and the birth of modern Western philosophy with René Descartes; from the famous Enlightenment thinkers of John Locke, George Berkeley, David Hume, and Immanuel Kant, through to Friedrich Nietzsche, and the subsequent existentialism of the 20th century spearheaded by Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir; and from the post-war moral and political insights of thinkers like Hannah Arendt, to modern figures like Daniel Dennett tackling consciousness and AI — there are too many philosophical greats to mention here. But what they all have in common is that they had and have profoundly original and insightful things to say about some of humanity’s deepest shared problems: they offer timeless wisdom we could all seriously benefit from digesting.

For, indeed, there is comfort in the thought that people from all over the globe, at all points in human history, have grappled with the very same questions — and shared the same bewilderment with existence — as we do today. Why are we here? What are our lives for? How can we know anything about the world? Though their roots are ancient, the problems of philosophy are as alive and nourishing as ever before.

Continue learning

If you’re interested in learning more about philosophy, check out our follow-up piece, Why Is Philosophy Important Today, and How Can It Improve Your Life?, as well as our bite-size Life’s Big Questions course, which distills the great philosophers’ answers to some of life’s most difficult and enduring questions: Why does anything exist? Is perception reality? What is consciousness? Do we have free will? How should we spend our lives?

Learn more and enroll in our Life’s Big Questions course today, and by this time next week, you’ll understand philosophy’s best answers to these questions, have clarity on exactly which topics interest you, and know the best further reading for continuing your philosophical journey.

Life’s Big Questions: Your Concise Guide to Philosophy’s Most Important Wisdom

Why does anything exist? Do we have free will? How should we approach life? Discover the great philosophers’ best answers to life’s big questions.

★★★★★ (100+ reviews for our courses)

Latest Course Reviews:

★★★★★ Wonderful

Wonderful! So clear and inviting to use. Just the right level of challenge. Felt like I was really learning. My favorite chapter was the one on Consciousness - what is it? I wonder about this all the time. Thank you for doing this, Jack. Your work is such a gift.VERIFIED BUYER

Mary T. on 8 July 2024★★★★★ Clear and concise

Fun and enjoyable. Clear and concise. Easy to navigate. Easy to get involved in discussion. Free will was my favorite chapter. Very relevant subject for which philosophy has a great deal to contribute.VERIFIED BUYER

Roger M. on 7 July 2024★★★★★ Really enjoyed

Just completed Life's Big Questions, which I really enjoyed reading. Thank you so much for putting it together. It really improved my understanding of so many points, particularly the chapters on Is Life real and free will.VERIFIED BUYER

Asad B. on 22 March 2024