Arne Næss’s Deep Ecology: Reevaluating Our Place in Nature

Arne Næss’s famous distinction between ‘shallow’ and ‘deep’ ecology is a call to reevaluate our place in nature: the world is not a resource to be exploited, it is the root of our humanity. The more we degrade the biosphere, the more alienated from ourselves we become.

Do we have a responsibility to preserve the wider environment? Or is the universe simply there to be used for human benefit?

Collective human activity betrays a presumption of the latter. We cut down forests; we blow up mountains; we funnel waste into rivers and seas.

Industry views the world as something to be packaged for human consumption, and its right to do so is rarely questioned. As environmental scientist G. Tyler Miller puts it in Living in the Environment:

The American attitude (and presumably that of most industrialized nations) toward nature can be expressed as [these] basic beliefs. 1. Humans are the source of all value. 2. Nature exists only for our use. 3. Our primary purpose is to produce and consume. Success is based on material wealth. 4. Production and consumption must rise endlessly because we have a right to an ever increasing material level of living.

Even if we don’t all personally accept these beliefs, Miller adds, “we act individually, corporately, and governmentally as if we did — and this is what counts.”

Norwegian philosopher Arne Næss spent a lifetime challenging what he saw as the corrosive anthropocentrism at the heart of our modern worldview.

Humanity is a tiny part of an enormous symbiosis that has developed over millions of years, Næss reminds us. There is no hierarchy here. Once you truly grasp how ecosystems work, you realize the food ‘chain’ is more an interdependent web. All life seeks to persevere, but its perseverance depends on all other life.

Nature thus doesn’t exist to serve humanity. Birds, plants, rivers, mountains, fish, insects, reptiles, oceans, mammals all have just as much of a basic right to life and existence as we do. As Næss puts it:

The ecological field worker acquires a deep-seated respect, even veneration, for ways and forms of life. He reaches an understanding from within, a kind of understanding that others reserve for fellow men and for a narrow section of ways and forms of life. To the ecological field worker, the equal right to live and blossom is an intuitively clear and obvious value axiom.

Acknowledging the value of other beings doesn’t mean denying the reality that life must consume other life to survive; it just means approaching such consumption with respect rather than entitlement, and limiting it to our vital needs.

We could apply such regard, too, if beings pose a threat to us or our loved ones, Næss explains:

We don’t say that every living being has the same value as a human, but that it has an intrinsic value which is not quantifiable. It is not equal or unequal. It has a right to live and blossom. I may kill a mosquito if it is on the face of my baby but I will never say I have a higher right to life than a mosquito.

It’s within this context that Næss makes his famous distinction between ‘shallow’ and ‘deep’ ecology.

Shallow ecology vs. deep ecology

Shallow ecology is focused on easing environmental destruction within the current paradigm of human dominance. It seeks to do things like reduce air pollution, purify water supplies, and clear plastic from the oceans — all without challenging the fundamental systems governing our use of nature, and usually with the goal of protecting human production and standards of living.

Deep ecology, meanwhile, wants to go deeper in its questioning of our relationship to the environment. It’s not so much a case of solving the technical problems of reducing pollution while maintaining production; it’s a total reconceptualization of humanity’s place in nature — a case of wondering whether boundless production really leads to lives worth wanting.

The idea is that, if you can interrogate the root of the ecological crisis, then a lot of the higher-order problems disappear.

The routine destruction of ecosystems, for example, is a side effect of society’s tacit belief that the good life involves vast wealth, superyachts, private jets, perpetual production, evermore consumption.

You can work on initiatives that find clever ways to mitigate the negative consequences of all this; but a definitive response means confronting the basic values and beliefs driving it.

This is the task of deep ecology. As Næss formulates it, deep ecology rejects humanity’s status as master of nature and asserts the inherent value of all life.

Næss and George Sessions presented the Deep Ecology Platform in 1984. It consists of eight simple points they think capture the broad principles of the movement, upon which other thinkers, scientists, and activists are encouraged to build their own philosophies. Here are the first three points:

1. The well-being and flourishing of human and nonhuman life on Earth have value in themselves… These values are independent of the usefulness of the nonhuman world for human purposes.

2. Richness and diversity of life forms contribute to the realization of these values and are also values in themselves.

3. Humans have no right to reduce this richness and diversity except to satisfy vital needs.

The eight points build in specificity, with the latter calling for far-reaching ideological change,

appreciating life quality (dwelling in situations of inherent worth) rather than adhering to an increasingly higher standard of living.

Rather than recognize private luxury as life’s ultimate prize, we might try to cultivate the profound value that comes with feeling connected to the world around us.

But why change? What’s going to trigger this shift in values?

But what’s our motivation? Why would we welcome such an ideological shift? Crucially, Næss doesn’t invoke morality here: he actually thinks moralizing about the environment is a rather patronizing, tactless approach.

If people see it as their ‘duty’ to ‘sacrifice’ their lifestyles for the ‘sake’ of the environment, change will be slow, and heels will be dragged.

Instead, he wants to point out that our current models of ‘self-realization’ — i.e. material success, status, consumption — are ultimately self-defeating, and have led to widespread spiritual alienation. Næss thinks deep ecology offers us all a much surer path to happiness and tranquility.

Why? Well, we fundamentally underestimate ourselves, he argues. Our lives tend to be built around the narrow desires of the ego. We might consider the needs of our friends and family, too.

But Næss urges us to expand our conception of ‘self’ to incorporate the deeper natural processes and environments that make us who we are.

Myriad spiritual traditions suggest genuine self-realization comes not from the endless pursuit of material success but in promoting our very essence as human beings. Næss agrees: it’s a result of understanding our interrelatedness with the world, as well as

the deep pleasure and satisfaction we receive from close partnership with other forms of life. The attempt to ignore our dependence and to establish a master-slave role has contributed to the alienation of man from himself.

Næss thus builds on the Deep Ecology Platform to develop his own personal eco-philosophy or ‘ecosophy’, which he dubs Ecosophy T.

That all beings have intrinsic value and strive to realize this value is an axiom grounded in Næss’s broader metaphysics, which is informed by Spinoza, Buddhism, and indigenous philosophies.

Næss envisions the cosmos as a vast relational net, what he calls a ‘total image field’. Brahmic philosophies may call this ‘Oneness’, and Spinoza ‘God’: the idea is there’s an underlying unity to the materials of existence.

There are no distinct beings; strictly speaking, there is just one existing Being, and particular manifestations of this same essence.

‘Individual’ entities, then, are not isolated but ‘knots’ in this shared essential net. What makes entities unique is their particular interrelations with other entities. If a link between entities is severed, both are fractured and changed.

On this view, it should be clear why biodiversity is so obviously valuable for the deep ecologist: it enhances the possible connections we can form with other entities, and thus enriches our very essence.

If people better understood the interrelated character of the biosphere, they too would value biodiversity. The problem here, then, isn’t one of moral deficiency; it’s merely ignorance, compounded by the egoistic traps of consumerism.

The philosophy of privilege? Or a much needed reset on our relationship to nature?

One might think Næss’s worldview is rooted in privilege. Concern for the environment is a luxury for people with the time and capacity required to enjoy nature.

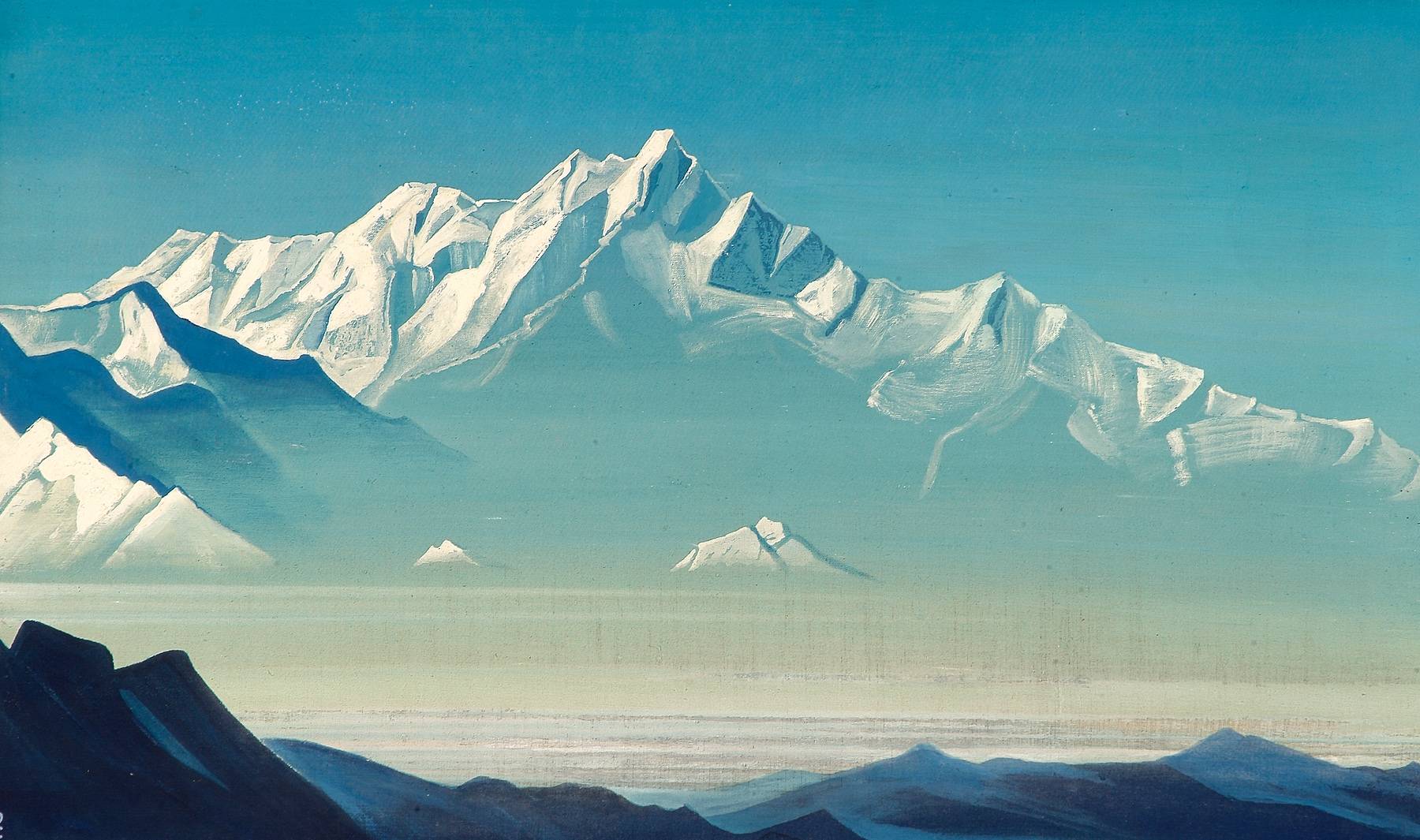

But self-realization is for all human beings, rich or poor, Næss suggests, and he was very much inspired by the indigenous communities he encountered across the globe — how the Sherpa people discuss the mountains, for instance, or Intuit culture’s harmonious approaches to the Arctic.

Late philosopher Helen de Cruz notes another example in her wonderful essay on Næss and Spinoza:

In a letter in 1988, Næss tells the story of an indigenous Sámi man who was detained for protesting the installation of a dam at a river, which would produce hydroelectricity. In court, the Sámi man said this part of the river was ‘part of himself’. Differently put, if the river were altered, he would feel that the alteration would destroy part of himself. In his view, personal survival entailed the survival of the landscape.

Such profound connections to nature may feel a bit beyond our sanitized modern lives, but I don’t think it only has to be grand wild landscapes that necessarily apply here.

Think of the local places that you cherish. It could be a park, a pond, a meadow. I live in London, for instance, but near me is a beautiful grove of trees; on most days I walk among them. Their branches shade me in the summer and shelter me in the winter; I have anxiously marched by them and tranquilly strolled through them.

The trees — as well as the birds nestling in them and the squirrels darting up their trunks — are part of my daily environment, an intimate feature of my lived experience.

If the trees were to go, my lived experience would immediately degrade. My relationships to the trees, the animals, as well as the animals’ own relationships: all would disappear. It might seem a small thing, but the world really would feel poorer.

It’s exactly this kind of ‘spiritual’ or ‘essential’ impoverishment that Næss thinks we need to pay more attention to.

Losing the places where we walk, think, reflect, where we get to observe the richness and diversity in the Being of other lifeforms — this profoundly impairs our potential for self-realization.

Yet all over Planet Earth the loss of such natural places, as well as the intimate relationships human and nonhuman beings have to them, is utterly routine.

Such destruction takes place in the name of greater production and consumption, and is driven by a shallow, misguided conception of what ‘self-realization’ really means.

We will never realize ourselves through trying to hoard as much stuff and status as possible, Næss suggests, nor through exploiting and homogenizing our environment. We are looking in the wrong places and chasing the wrong things.

Genuine self-realization, a salve for our spiritual alienation, will only come if we each cultivate greater awareness of our place within nature’s totality — and for that we need the totality.

From ego-centrism to eco-consciousness

What appears to distinguish humanity from other known beings is that we have a capacity for understanding the value of preserving or destroying an ecosystem. This increased awareness of the workings of nature has for centuries made humanity feel entitled to harness it for its own benefit.

Næss’s point is that, if we really want to help ourselves, we need to change this mindset. Nature is not a resource to be exploited. We are not its masters. We do not have a greater right to exist than anything else.

Rather than nature’s rulers, our increased awareness perhaps means we have a responsibility to act as its guardians.

Two paths thus lie before us.

We could blindly proceed with growth for growth’s sake, sever the connections that make us who we are, and forever exile ourselves from our own home.

Alternatively, we could reconceptualize our relationship with nature. We could recognize how our fundamental connections to the world anchor our identity. By protecting and nurturing those connections, we could permit the many entities of Being — ourselves included — to unfold and achieve self-realization.

What do you make of Næss’s philosophy?

- Does Næss’s deep ecology resonate with you?

- Or do you think the universe, including other life, is a resource for humanity to use as it sees fit?

- If you do like aspects of Næss’s approach, how might we induce the mass reconceptualization and self-realization he thinks we need?

To inform your answers, you might enjoy the following related Philosophy Breaks:

- Beyond Money: Martha Nussbaum on Living a Flourishing Human Life

- On Living Meaningfully in a Vast Universe: Robert Nozick

- ‘Dao’ in Chinese Philosophy: Harmonizing with the Way

- Seneca: To Find Peace, Stop Chasing Unfulfillable Desires

- Mono No Aware: Beauty and Impermanence in Japanese Philosophy

- Peter Singer On the Life You Can (and Should) Save

- Finding Rapture in the Humdrum: Cultivating Wonder for Everyday Life

Get one famous philosophical idea in your inbox each Sunday

If you enjoyed this article, you might like my free Sunday breakdown. I distill one piece of wisdom from philosophy each week; you get the summary delivered straight to your email inbox, and are invited to share your view. Consider joining 25,000+ subscribers and signing up below:

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying my free Sunday Breakdown

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox.

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

About the Author

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (100+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Take Another Break

Each break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your philosophical curiosity.