Beyond Money: Martha Nussbaum on Living a Flourishing Human Life

With her famous ‘capabilities approach’, the philosopher Martha Nussbaum argues that wealth and satisfaction are very limited measures of the good life; instead, she offers 10 essential capabilities by which to judge if someone can live a full, flourishing human life.

We all need money to survive in society; but if we earn enough to live comfortably, then we should be careful not to fall for the illusion that happiness can only be secured through more and more accumulation.

So cautions the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer in his 1851 work, The Wisdom of Life:

It is manifestly a wiser course to aim at the maintenance of our health and the cultivation of our faculties, than at the amassing of wealth.

Yet still, he laments,

men are a thousand times more intent on becoming rich than on acquiring culture, though it is quite certain that what a man is contributes much more to his happiness than what he has.

Schopenhauer is not the first philosopher to question if wealth accumulation really leads to a happy or flourishing life.

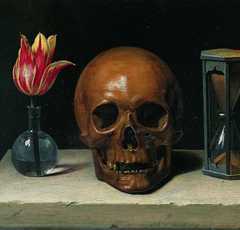

Ancient Greek sage Epicurus warns that “nothing is sufficient for the person who finds sufficiency too little”, while Roman Stoic thinker Seneca implores us to understand that time, not money, is our most precious resource.

But while Schopenhauer emphasizes the value of intellectual refinement, Epicurus tranquility, and Seneca time, contemporary philosopher Martha Nussbaum seeks to offer a more holistic picture of what a flourishing human life really requires.

Yes, we need money to survive; but if we are to thrive, then what are the basic, non-negotiable capabilities we should cultivate?

Nussbaum’s Capabilities Approach

In her 1999 work Women and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach, Nussbaum presents a version of her so-called ‘capabilities approach’ in the context of international social justice.

As with judgments of our individual wealth and well-being, progress in global development is often measured by economic metrics like a country’s GDP. Occasionally there might also be some kind of ‘happiness survey’.

But if our goal is to make societies of truly flourishing people, Nussbaum argues, channeling Aristotle, then we cannot just look at economic measures or perceived desire-satisfaction.

Instead, we must develop a fuller picture of individual dignity and prospective life quality, asking: how are people actually living? Do they have a range of choices available to them? Is it possible for individuals to really fulfill their human potential?

As Nussbaum clarifies in her 2002 paper, Capabilities and Social Justice:

The central question asked by the capabilities approach is not, “How satisfied is this woman?” or even “How much in the way of resources is she able to command?” It is, instead, “What is she actually able to do and be?”

Nussbaum thus compiles what she thinks are ten essential, cross-cultural capabilities for living a full human life.

While her list has evolved throughout her work, we can summarize the capabilities, based on those in Women and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach, as follows:

- Life. The ability to live a life of typical human length, without having it cut short or diminished to a state not worth living.

- Bodily Health. The opportunity to maintain good physical health, including access to reproductive care, adequate nutrition, and safe housing.

- Bodily Integrity. The freedom to move freely from place to place, and to have control over one’s own body.

- Senses, Imagination, and Thought. The capacity to use one’s senses, imagination, and intellect in a ‘truly human way’ — supported by adequate education. This includes freedom of expression, religious practice, artistic creation, and the ability to seek meaning and pleasure in life without fear or undue pain.

- Emotions. The ability to form attachments and experience a full range of human emotions: loving others, grieving losses, feeling justifiable anger, etc.

- Practical Reason. The capacity to form and critically reflect on one’s own values, and to make meaningful life decisions based on that reflection.

- Affiliation. The ability to engage in loving, meaningful, and respectful relationships — showing empathy, compassion, and a sense of justice and friendship — supported by institutions that foster social connection.

- Other Species. The capacity to engage with, care for, and live harmoniously alongside animals, plants, and the natural environment.

- Play. The opportunity to enjoy leisure, have fun, laugh, and participate in recreational activities.

- Control Over One’s Environment. Political: the ability to actively participate in political life, including the rights to free speech, association, and democratic engagement. Material: the real opportunity to own property, seek employment on equal terms, and be protected from unjust interference — such as unwarranted searches or seizures.

Capabilities might make us think of human rights: basic liberties shared by all. Not imposing a specific vision of the good life, but empowering people to live one of their own choosing.

But Nussbaum thinks capabilities take us beyond human rights, because they emphasize functioning potential, not just entitlements.

They also offer us a more nuanced, richer approach for thinking about morality. If individual actions or wider policy inhibit or even block an essential human capability, then they do not cohere with the good.

On this view, if governments wish to create a ‘successful’ society, they must guarantee their citizens not just rights, but real opportunities to achieve a threshold level of each fundamental human capability.

When reflecting on the success of a particular society, then, rather than simply base our judgment on GDP or even perceived citizen satisfaction, we should ask: do all of these individuals have a genuine chance of leading lives that fulfill their potential as human beings?

The Capabilities Approach in practice

Nussbaum’s key argument is that we shouldn’t let society be guided by the wrong metrics just because those metrics are currently easier to measure:

Resource-based approaches simply substitute something easy to measure for what really ought to be measured, a heap of stuff for the richness of human functioning. Preference-based approaches do even worse, because they not only don’t measure what ought to be measured, they also get into quagmires of their own, concerning how to aggregate preferences…

While she concedes the details will likely require refinement, Nussbaum is certain that the capabilities approach is a step in the right direction for making sense of what we could possibly mean by a ‘successful’ human society: not how much stuff it produces, not even how satisfied it is; but the capacity of its citizens to fulfill their human potential…

Of course, Nussbaum developed her framework in the context of global development. Political solutions will be needed for implementing and measuring this kind of schema at scale. The UN’s Human Development Index (HDI) is an initial effort in this department, and it was greatly informed by the capabilities approach.

But there’s nothing stopping us from using the capabilities approach as a lens through which to scrutinize our own lives, too.

Money is crucial for surviving our society, we might observe, but alone it cannot help us thrive in it. We thus need to release ourselves from primarily judging the health of a society or the wealth of an individual, including ourselves, merely by material worth.

As Schopenhauer puts it:

you may see many a man, as industrious as an ant, ceaselessly occupied from morning to night in the endeavor to increase his heap of gold… And if he is lucky, his struggles result in his having a really great pile of gold, which he leaves to his heir, either to make it still larger, or to squander it in extravagance. A life like this, though pursued with a sense of earnestness and an air of importance, is just as silly as many another which has a fool’s cap for its symbol.

Rather than tie our human worth to a singular metric like money, perhaps we could consider Nussbaum’s capabilities, and wonder whether there are other departments in which we might strive to become rich: our relationships with others, our capacity for presence and play, the connection we have to the natural world…

We might ask ourselves: in the different capabilities I could cultivate, where would paying more attention make an actual difference to my life, well-being, and the fulfillment of my human potential?

What do you make of Nussbaum’s capabilities approach?

- Do you think her list covers the essential capabilities needed for a happy and full life?

- Is the list as neutral and cross-cultural as Nussbaum thinks?

- Does thinking in terms of capabilities offer a good alternative to resource- and satisfaction-based approaches to the good life?

- Are there any other capabilities you think might be needed for a flourishing life?

To inform your answers, you might enjoy the following related Philosophy Breaks:

- Peter Singer On the Life You Can (and Should) Save

- John Rawls: How a ‘Veil of Ignorance’ Can Help Us Build a Just Society

- Arne Næss’s Deep Ecology: Reevaluating Our Place in Nature

- Byung-Chul Han’s Burnout Society: Our Only Imperative is to Achieve

- Ubuntu Philosophy: Wealth Resides in the Health of the Community

- Elizabeth Anderson on the Tyranny of Being Employed

- The ‘Golden Mean’: Aristotle’s Guide to Living Excellently

- Seneca: To Find Peace, Stop Chasing Unfulfillable Desires

- How to Live a Fulfilling Life, According to Philosophy Break Subscribers

Get one famous philosophical idea in your inbox each Sunday

If you enjoyed this article, you might like my free Sunday breakdown. I distill one piece of wisdom from philosophy each week; you get the summary delivered straight to your email inbox, and are invited to share your view. Consider joining 25,000+ subscribers and signing up below:

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying my free Sunday Breakdown

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox.

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

About the Author

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (100+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Take Another Break

Each break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your philosophical curiosity.