Confucius: Rituals Grind Our Characters Like Pieces of Jade

If we are to develop ourselves morally, ancient Chinese philosopher Confucius argues, it is not just our individual habits that matter: our shared, cultural habits play a crucial role.

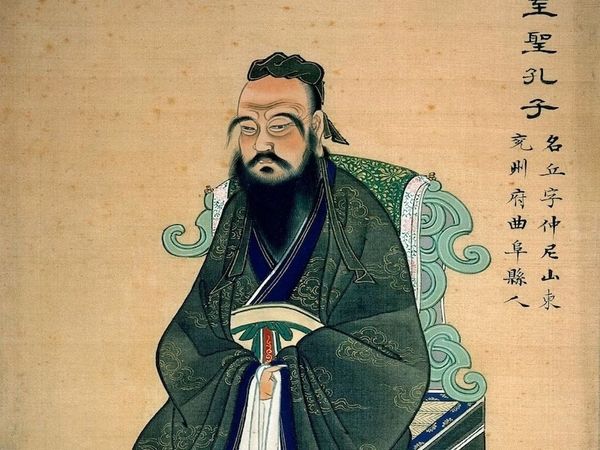

Confucius (551 - 479 BCE) was an ancient Chinese philosopher who founded the school of Confucianism, a philosophy that has shaped the history of Chinese culture more than any other.

A pertinent insight into Confucius’s philosophical project comes from his statement in The Analects (a collection of his teachings) that:

I transmit rather than innovate. I trust in and love the ancient ways.

Living with the threat of chaotic upheaval on the horizon (China was soon to enter its Warring States period), Confucius was intent on reaching back into the past, finding what worked, and ‘transmitting’ the recipe for stability and wisdom to the present day.

It is this penchant for tradition that informs one of the most distinctive aspects of Confucius’s philosophy: its emphasis on ritual in shaping who we are and cultivating our moral characters.

What does ritual mean for Confucians?

The word ‘ritual’ may bring to mind rather stuffy or formal ceremonial practices, and while these are definitely included in what Confucians are referring to, ritual also means general day-to-day etiquette and social custom — anything that is a shared human activity, anything that brings people together.

So, it could be a wedding, or it could be something as simple as a handshake: the Confucian point is that these cultural practices and social customs have a key role to play in shaping our moral lives, for they are the language in which we communicate our shared humanity and respect for one another.

This insight becomes the basis for Confucian ritual psychology, in which the proper performance of ritual is regarded as foundational to reforming desires, honing our characters, and developing our moral dispositions.

If our characters are like pieces of jade, then rituals help grind and polish them.

As the contemporary scholar David Wong illuminatingly puts it in his 2008 essay, Chinese Ethics:

Children learn what their behavior means to others, and what it should mean, by learning how to greet each other, make requests, and answer requests, all in a respectful manner. Much of our everyday experience of moral socialization lies in the absorption of or teaching to others of customs that are conventionally established to mean respect, gratitude, and other ethically significant attitudes.

In other words, while many moral theories may start with abstract principles about what ‘goodness’ means (like, for instance, Aristotle’s golden mean), Confucianism starts with everyday social principles about what makes for a harmonious society.

By learning these social principles and customs, we go a long way to developing our moral characters.

In The Analects, Confucius emphasizes this by discussing how rulers can harness the power of ritual rather than force to encourage good behavior:

If you try to guide the common people with coercive regulations and keep them in line with punishments, the common people will become evasive and will have no sense of shame. If, however, you guide them with Virtue, and keep them in line by means of ritual, the people will have a sense of shame and will rectify themselves.

Confucius’s key innovation and insight — one we see utilized by religions, and more nefariously by propagandists and dictatorships — is to recognize that the result of a ritual is not just its promised reward or outcome, but the moral shaping of all its participants.

If we are to develop ourselves morally, Confucius says, it is not just our individual habits that matter: our shared, cultural habits play a crucial role.

Rituals induce certain behaviors

The power of ritual for Confucians becomes clear when we consider something like a funeral. Funerals involve shared practices like wearing certain clothes, attending certain locations, and performing certain ceremonies that mark the occasion and create an atmosphere fertile for respect and mourning.

These practices tell all participants that it’s okay to show emotion and grieve, lend structure to the process of saying goodbye to a loved one, and offer a path for what to do in an otherwise pathless time.

Funerals encourage us to cultivate an attitude of compassionate respect: we suppress our own needs to participate in the shared harmony of the occasion.

Another example is a regular family dinner, in which different members of the family may wait for one another to sit down before eating, have a rule of ‘no technology at the table’, and so on, creating an atmosphere in which there is more potential for human connection.

Yet another, more everyday example is waiting in line: a queue demonstrates the basic respect each member has for the person in front and behind them, and people who jump the queue are chastised as rude or arrogant for putting their needs before those of others — for setting a poor example, and making the world feel a less respectful and harmonious place.

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 14,000+ subscribers enjoying my free Sunday Breakdown

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox.

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

By encouraging certain behaviors, rituals thus shape who we are. They place a check on our own individual desires and needs by demanding instead that we act in a certain way that promotes the harmony of the group.

Once we begin to think about them, we notice rituals everywhere, and recognize the social — and moral — importance of learning the appropriate ways to act in different situations.

Of course, not all rituals or shared cultural practices necessarily promote harmony or opportunities for moral development.

Think of the now annual Black Friday sale, an event created to induce a consumer mindset and encourage mass spending; or social practices that entrench particular hierarchies or power structures.

Confucius had very specific ideas for the rituals we should participate in, largely based on practices from the Zhou dynasty of ancient China.

The extent to which Confucianism allows for the evolution of the rituals in which we participate is a hot topic of discussion among scholars, and one I’ll return to in a future article.

Performing rituals beautifully

What Confucius really wants us to understand is that rituals form a core part of what it means to be human: we cannot live fully-realized human lives without performance in ritual.

Our approach to ritual, then, shouldn’t be rooted in a cold sense of obligation or a ‘going through the motions’: if we wish to develop morally, the attitude we bring to ritual performance — the amount of ourselves we give to it — is paramount.

In a 2004 essay in Confucian Ethics, the scholar Craig K. Ihara helpfully suggests we think of the rituals of everyday life as a ‘dance’ we perform with others.

Wong, commenting on this suggestion, adds:

Consider that a graceful and whole-hearted expression of respect can be beautiful precisely because it reflects the extent that the agent has made this moral attitude part of her second nature. The beauty has a moral dimension.

At its best, ritual is thus a beautiful, graceful, coordinated interaction with others that expresses mutual respect.

The quality or aesthetic of our performance is a major part of the resulting ethic it expresses, Confucians think: by performing rituals beautifully and full-heartedly, we demonstrate what it means to be an exemplary person.

So, the next time you find yourself in a ritual situation — be it as a guest at a formal ceremony, or simply as a friend greeting another friend — remember Confucius: our approach to ritual encapsulates our approach to life.

Learn more about Confucianism

If you’re interested in learning more about Confucian philosophy, you might like our article detailing the two Confucian philosophers Mengzi vs. Xunzi disagreeing on human nature. We’ve also assembled a list of the best introductory books on Confucianism here.

You may also be interested in our new guide, How to Live a Good Life (According to 7 of the World’s Wisest Philosophies), which compares the wisdom of Confucianism to six rival philosophies for life.

In the meantime, what do you make of this analysis? Has ritual or etiquette played an important role in your life? Do you agree that learning societal norms and performing them well is a sign of respect to our fellow citizens? Or does this kind of thinking over-suppress the freedom of the individual?

How to Live a Good Life (According to 7 of the World’s Wisest Philosophies)

Explore and compare the wisdom of Stoicism, Existentialism, Buddhism and beyond to forever enrich your personal philosophy.

Get Instant Access★★★★★ (50+ reviews for our courses)

About the Author

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 14,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (50+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Take Another Break

Each break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your philosophical curiosity.