Finding Rapture in the Humdrum: Cultivating Wonder for Everyday Life

How, even as seasoned veterans of experience, can we preserve a sense of wonder throughout our lives? Advice from Pablo Picasso, Rachel Carson, and Hermann Hesse.

“Every child is an artist,” declares Pablo Picasso. “The problem is how to remain an artist once we grow up.” Indeed, novelty catalyses the production of awe, and children hold the advantage of having a relatively small bank of experience to draw from. Encountering the sea for the first time, hearing the silence of snow, tasting a lemon…

Such wonders become commonplace all too soon. But research from the University of California links regular ‘awe experiences’ to improved critical thinking, reduced depressive rumination, increased generosity, and better connectedness.

If we wish to enjoy such benefits, we must find ways to overcome the problem identified by Picasso. How, even as seasoned veterans of experience, can we preserve a sense of wonder throughout our lives?

One approach, well articulated by the celebrated conservationist Rachel Carson, is to increase our sensitivity to the ways in which everyday life remains perpetually novel.

In her 1965 work The Sense of Wonder, Carson offers a useful trick for bringing forth an attentive mindset:

One way to open your eyes is to ask yourself, ‘What if I had never seen this before? What if I knew I would never see it again?’

Consider the scene before you now. Wherever you are reading these words, be it at home, on a train, in a cafe: this moment has never happened before, and will never happen again.

Reflecting on its impermanence raises the stakes and focuses the attention — and then the power of your attention can do the rest. For, as novelist Henry Miller puts it in Black Spring:

I have a theory that the moment one gives close attention to anything, even a blade of grass, it becomes a mysterious, awesome, indescribably magnificent world in itself. I have tried this experiment a thousand times and I have never been disappointed.

For the novelty of experience to reveal itself, all we have to do is attend to it.

Though you may have been wherever you currently are before, you haven’t breathed this oxygen, read these words amid this exact background of light and sound.

Even in situations that seem particularly repetitive, like cleaning our teeth each morning and night, all we need to do is zoom out: between brushings, the Earth will have fallen thousands of miles through space…

The great 19th-century polymath Goethe baked such attention into his life’s purpose, once exclaiming “I am here, that I may wonder!”

A century later, the writer Hermann Hesse reflected on the merit of such ‘Goethean wonder’, suggesting that truly contemplating the world — truly attending to and feeling wonder for it — can help dissolve the separations we artificially impose upon life.

In moments of awe, Hesse writes in a substantial yet bewitching passage from Butterflies: Reflections, Tales, and Verse, we experience the unity of all that exists:

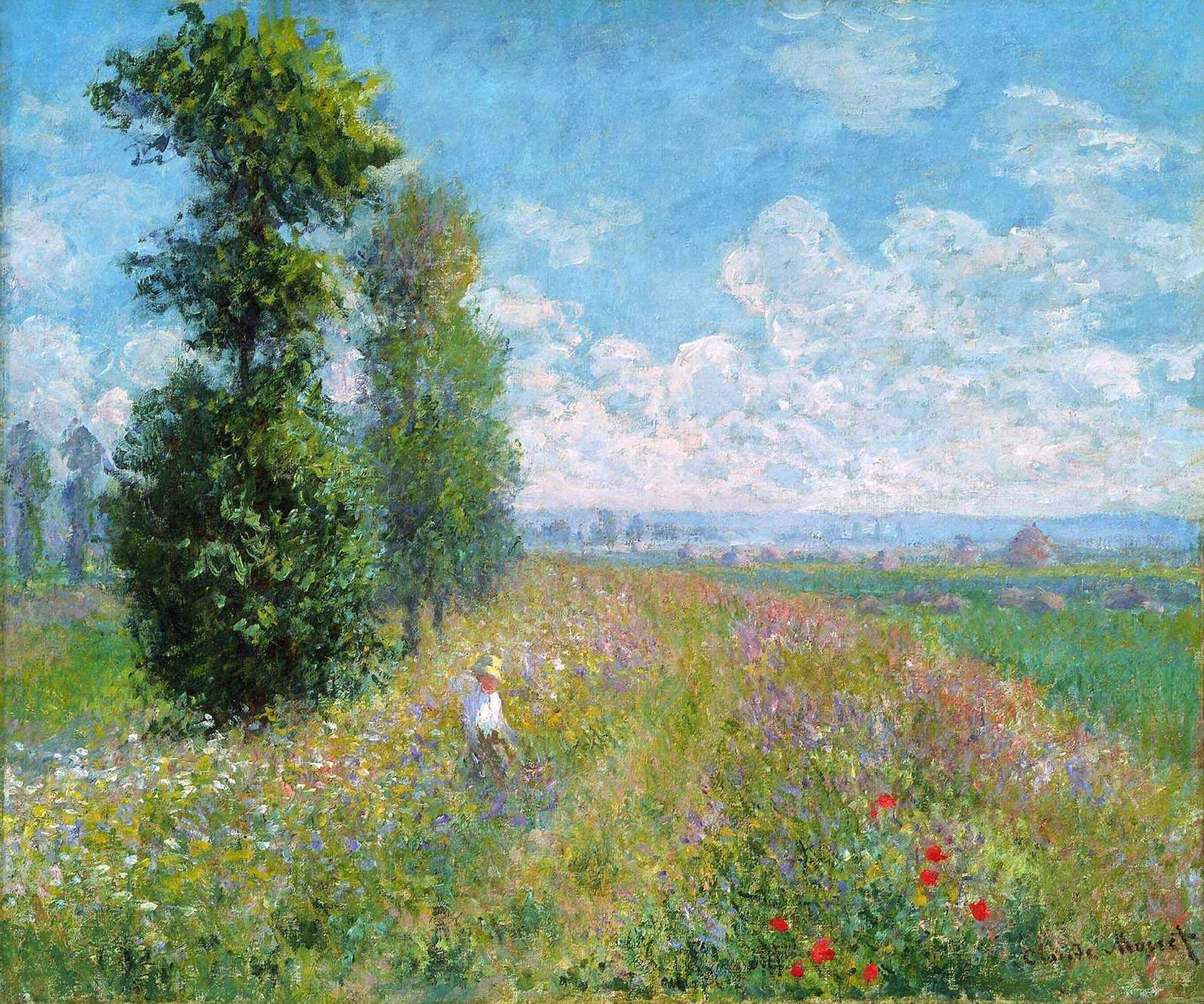

Wonder is where it starts, and though wonder is also where it ends, this is no futile path… whenever I experience part of nature, whether with my eyes or another of the five senses, whenever I feel drawn in, enchanted, opening myself momentarily to its existence and epiphanies, that very moment allows me to forget the avaricious, blind world of human need, and rather than thinking or issuing orders, rather than acquiring or exploiting, fighting or organizing, all I do in that moment is ‘wonder,’ like Goethe, and not only does this wonderment establish my brotherhood with him, other poets, and sages, it also makes me a brother to those wondrous things I behold and experience as the living world: butterflies and moths, beetles, clouds, rivers and mountains, because while wandering down the path of wonder, I briefly escape the world of separation and enter the world of unity.

For mindfulness and attentiveness are not just ‘nice to haves’, the reserve of conservationists, artists, and writers. Many philosophers regard ‘proper attention’ as one of the central features of a good life.

Iris Murdoch, for instance, argues attention has a moral dimension: our propensity for ethics is often rooted in the quality of our attention.

Buddhist thinker Thich Nhat Hanh, meanwhile, writes in The Miracle of Mindfulness that

Every day we are engaged in a miracle which we don’t even recognize: a blue sky, white clouds, green leaves, the black, curious eyes of a child — our own two eyes. All is a miracle.

The greater our awareness of this miraculous present, Hanh suggests, the greater our capacity for gratitude and peace. (I consider Buddhist and Stoic tools for clearing our preoccupied minds in my companion article, The Last Time Meditation.)

Carson agrees with Hanh. In a beautiful passage, she discusses why feeling awed before the mystery of the world can imbue us with immense strength:

What is the value of preserving this sense of awe and wonder? Is the exploration of the natural world just a pleasant way to pass the golden hours of childhood, or is there something deeper? I am sure there is something much deeper, something lasting and significant. Those who dwell among the beauties and mysteries of the earth are never alone or weary of life. Whatever the vexations of their personal lives, their thoughts can find paths that lead to inner contentment and to renewed excitement in living. Those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts. There is symbolic as well as actual beauty in the migration of the birds, the ebb and flow of the tides, the folded bud ready for the spring. There is something infinitely healing in the repeated refrains of nature – the assurance that dawn comes after night, and spring after winter.

The writer William Martin channels such wisdom into a wonderful poem from his 1999 book, The Parent’s Tao Te Ching:

Do not ask your children

to strive for extraordinary lives.

Such striving may seem admirable,

but it is the way of foolishness.

Help them instead to find the wonder

and the marvel of an ordinary life.

Show them the joy of tasting

tomatoes, apples and pears.

Show them how to cry

when pets and people die.

Show them the infinite pleasure

in the touch of a hand.

And make the

ordinary come alive for them.

The extraordinary will take care of itself.

What makes you full of wonder for life?

- Do you think Carson’s questions are helpful for focusing our attention?

- How do you cultivate awe and attention in the heat of the day-to-day?

- What did you last truly wonder at?

To inform your answers, you might enjoy the following related Philosophy Breaks:

- The Last Time Meditation: a Stoic Tool for Living in the Present

- Iris Murdoch: ‘Unselfing’ is Crucial for Living a Good Life

- Mono No Aware: Beauty and Impermanence in Japanese Philosophy

- Anicca: Our Collective Way of Life Won’t Exist Soon

- Arne Næss’s Deep Ecology: Reevaluating Our Place in Nature

- What’s Made the World Wonderful Recently?

Get one famous philosophical idea in your inbox each Sunday

If you enjoyed this article, you might like my free Sunday breakdown. I distill one piece of wisdom from philosophy each week; you get the summary delivered straight to your email inbox, and are invited to share your view. Consider joining 25,000+ subscribers and signing up below:

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying my free Sunday Breakdown

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox.

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

About the Author

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (100+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Take Another Break

Each break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your philosophical curiosity.