How To Set Better New Year’s Resolutions: Focus On Processes, Not Outcomes

As many of us set New Year’s resolutions for 2025, MIT philosophy professor Kieran Setiya argues that we might better serve ourselves by focusing on the quality of processes, not just the result of projects.

And so 2025 begins. Happy New Year, philosophers – I wish you all the best for the year ahead. Regardless of whether you’re into making specific resolutions, the beginning of January is a time of reflection, planning, and dreaming for many.

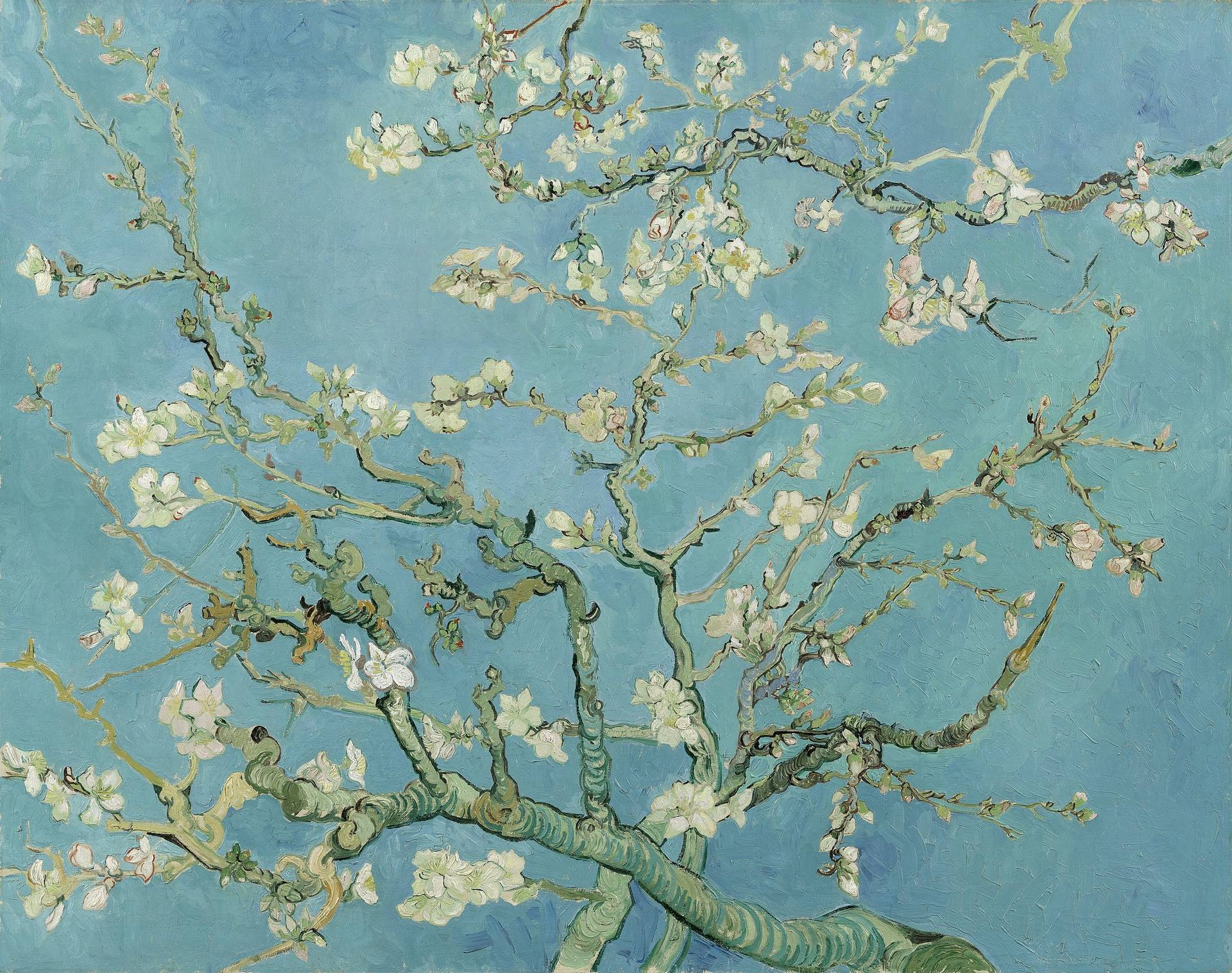

Remaining totally unmoved by the seductive New Year promises of rebirth, growth, and possibility is surely a challenge for even the most hardened of cynics... another spring awaits!

But, as philosophers, we must ask: if we do seek to improve our lives this year, what sort of resolutions should we be setting? Are certain kinds better or wiser than others?

For example, be it committing to learning a new skill, embarking on an exercise program, or even writing detailed five-year plans, many New Year’s resolutions take the form of projects.

And, typically, these projects are centered around shiny rewards. A stronger, fitter, healthier body; a bigger bank balance; an impressed peer group. With these kinds of resolutions, our eyes are on the prize: in the future, our lives will be better.

As I reflected on my own objectives and goals for 2025, I was reminded of a comment made by MIT philosophy professor Kieran Setiya about our emphasis on project-like structures.

In an interview I conducted with Setiya a year or so ago, he warns that focusing only on the outcome of projects, while tempting, risks draining meaning and happiness from our everyday activities.

“We tend to be, I think, a little bit too obsessed with project-like structures in our lives,” Setiya remarks:

When you’re focusing on a project, you’re aiming at something in the future, and then as soon as you achieve it, it’s over. What you’re doing is taking this thing that’s structuring your life and attempting to finish it – and thereby getting rid of the source of meaning in your life. The more you focus on things like that, the more you risk setting yourself up for evaluating your life in terms of success and failure. But it’s important to remember that not all activities are like that.

Setiya draws a distinction between telic activities and atelic activities, terms which originate from the Greek word telos, meaning ultimate object or aim:

While there are telic projects which aim at some sort of end state where they’re achieved, there are also atelic activities that don’t aim at a goal in this way. While you’re walking home, for instance, you’re also just walking, and there’s pleasure to be found in just walking with no urgent destination in mind.

Many New Year’s resolutions tend to be telic in structure: they aim at a desired future state. Setiya reminds us, however, that it is atelic activities that actually fill our days:

The more we recognize the value of the atelic activities we’re engaged in on a daily basis – like walking, eating, interacting with our loved ones – the less we’re structuring our lives entirely in terms of projects that will succeed or fail.

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox:

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

Reframing our New Year’s resolutions accordingly

It’s not like we can simply banish telic activities. Having something to aim for provides motivation and purpose. There’s a nice quotation from the philosopher and writer Robert M. Pirsig on this:

To live only for some future goal is shallow. It’s the sides of the mountain which sustain life, not the top. But of course, without the top you can’t have any sides. It’s the top that defines the sides. So on we go—

“Right,” Setiya agrees:

And you can’t really opt out. It’s not like the prospect of a human life totally unstructured by projects is a real one. It’s not that you can say, ‘I’m just not going to engage in a project.’ But the question is when you’re engaging in projects, how much do you also recognize where there is value in the process, and not just mortgage everything to the success and failure of your enterprise?

Indeed, the point here is not that we should ignore telic projects, but that we shouldn’t attach value only to their success or failure.

Our lives are not an outcome; they are an ongoing activity. By focusing on the quality of that activity, we are better able to actually make a difference to our day-to-day lives.

When setting resolutions, then, we should ask ourselves not just who we want to be in the future, but who we want to be day-to-day, on the way to that future. As Setiya puts it:

To some extent you can reframe this in terms of thinking about processes as primary and projects as secondary: that we engage in certain kinds of projects in order to be engaged in certain valuable processes.

In other words, we identify the activity first, and then build a project around it – for the activity itself holds value, not just whether we achieve some kind of result from it.

What kind of activities do you enjoy? Walking? Reading? Learning? Debating? Cooking? Drawing? Painting? Interacting with loved ones? Playing an instrument? Dancing? Being a good friend? Hiking? Gardening? Playing a sport?

What kind of projects would enable you to do more of those activities this year?

Maybe the best resolutions are made not when we obsess over some arbitrary future goal, nor when we crave a particular result, but simply when we promise ourselves we’ll commit more time to the atelic activities that nourish our souls.

What do you make of this analysis?

- Have you made any New Year’s resolutions for 2025?

- Do you think the success or failure of projects determines the success and failure of our lives?

- Or do you agree that we overemphasize outcomes, and should focus more on the value of the process?

Learn more philosophical approaches to self-cultivation

If you’re interested in learning more philosophical approaches to self-improvement and self-cultivation, you might enjoy the following related reads:

- Life is Hard: Interview with Philosopher Kieran Setiya

- The ‘Golden Mean’: Aristotle’s Guide to Living Excellently

- The Dichotomy of Control: a Stoic Device for a Tranquil Mind

- Epicureanism Defined: Philosophy is a Form of Therapy

- Seneca: To Find Peace, Stop Chasing Unfulfillable Desires

Finally, if you enjoyed this article, you might like my free Sunday breakdown. I distill one piece of wisdom from philosophy each week; you get the summary delivered straight to your email inbox, and are invited to share your view. Consider joining 25,000+ subscribers and signing up below:

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying my free Sunday Breakdown

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox.

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

About the Author

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (100+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Take Another Break

Each break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your philosophical curiosity.