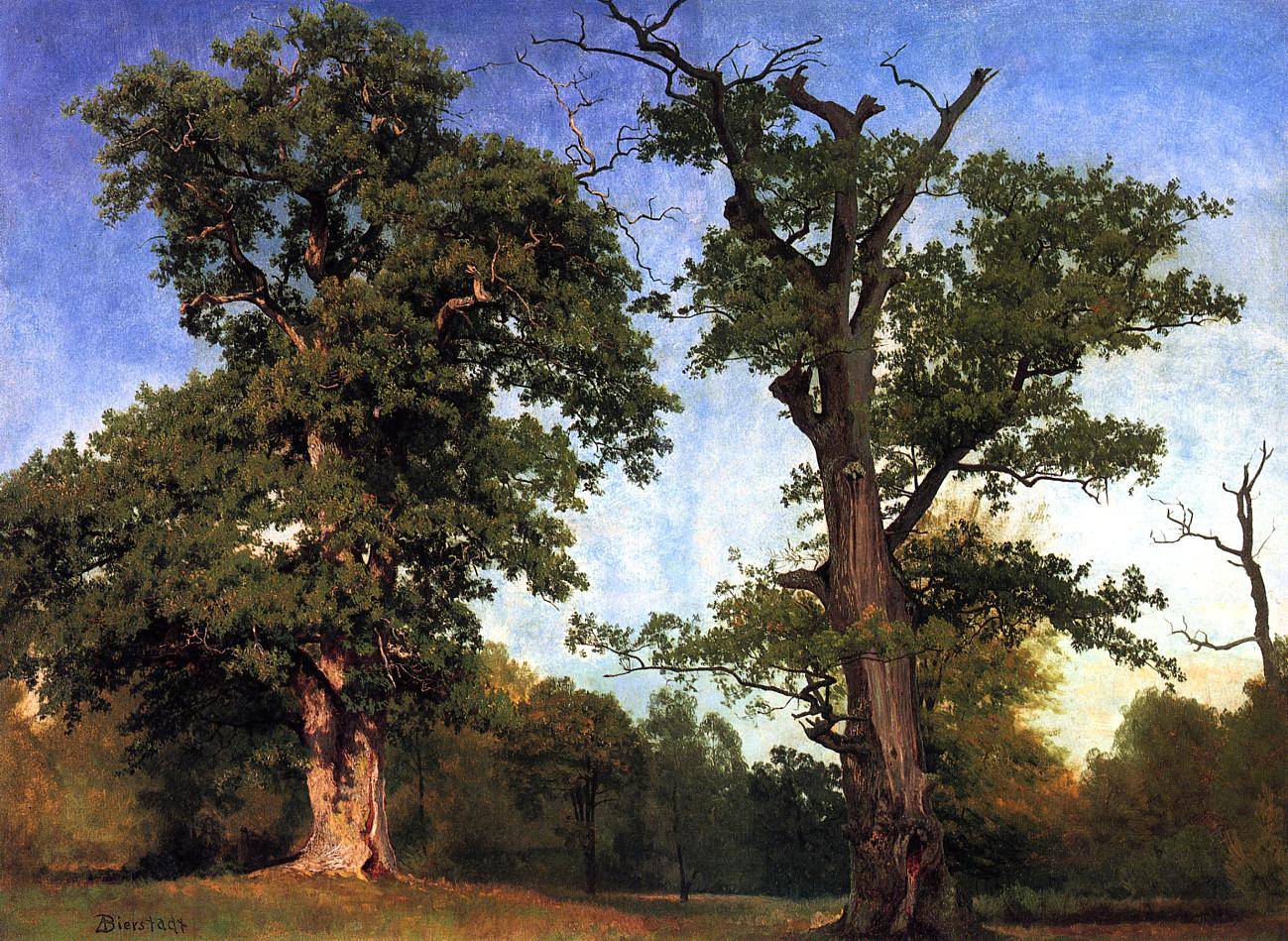

If a Tree Falls in the Forest, and There’s No One Around to Hear It, Does It Make a Sound?

The age-old question of whether a falling tree makes a sound when there’s no one around to hear it exploits the tension between perception and reality. This article explores possible answers and their consequences.

If a tree falls in the forest, and there’s no conscious being around to hear it, does it make a sound? Well, if by ‘sound’ we mean vibrating air, then yes, when the tree falls, it vibrates the air around it.

However, if by ‘sound’ we mean the conscious noise we hear when our sensory apparatus interacts with the vibrating air, then if no living being is around to hear the tree when it falls, there’d be no sensory apparatus for the vibrating air to interact with, and thus no conscious noise would be heard.

So, the answer to this age-old question seems to be simple: it depends on how we define ‘sound’. If we define it as ‘vibrating air’, the falling tree makes a sound. If we define it as a conscious experience, the lonesome falling tree does not make a sound.

There, problem solved.

The point of asking this question, however, is not so that it can be answered quickly and put aside.

Rather, its point is to draw out the rather strange tension between our two very different definitions of the word ‘sound’.

On the one hand, we classify sound as a mechanistic process that exists without us, ‘out there’ in the world. On the other, we regard it as a private conscious experience, its existence entirely dependent on us.

And when you dwell on this latter definition, you realize it doesn’t just extend to sounds. Everything we experience — everything we see, hear, smell, touch, taste — all of it depends on our sensory apparatus, on us. Without us, our experiences would not exist.

As the great 16th-century astronomer Galileo Galilei put it:

Tastes, odors, colors, and so on... reside only in consciousness. If the living creature were removed, all these qualities would be wiped away and annihilated.

Take away our senses, and the world of our experience would be replaced by a colorless, soundless, odorless, tasteless nothingness. Without us, what remains?

The reason our original question — When a tree falls in the forest, and there’s no one around to hear it, does it make a sound? — is such a teaser, is because it hits on a deeper question. Namely:

If there was no conscious life, would the physical universe exist?

Our kneejerk reaction to this question might be, ‘of course it would’. But let’s think about it again: if there was nothing conscious, then nothing would be experienced. There would be nothing resembling anything we call ‘physical existence’. No colors, no sounds, no smells, no tastes, no touch, no distinguishable objects, no sense of time, no sense of space...

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox:

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

Is consciousness more fundamental than matter?

Reflecting on this strange state of affairs, numerous great thinkers have concluded that consciousness must be more fundamental than the ‘stuff’ that consciousness experiences.

For instance, in his 1710 work, A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge, the philosopher George Berkeley discusses the absurdity of a world existing independently of our conscious minds:

It is indeed an opinion strangely prevailing amongst people that houses, mountains, rivers, and in a word all sensible objects, have an existence natural or real, distinct from their being perceived by the understanding… for what are the forementioned objects but things we perceive by sense? And what do we perceive besides our own ideas or sensations? And is it not plainly repugnant that any one of these or any combination of them should exist unperceived?

On this view, it is absurd to say a lonesome falling tree makes a sound. For Berkeley, it is absurd to say the tree, without a conscious mind there perceiving it, even exists. (You can learn more about his mind-bending arguments for this position in my philosophy break on Berkeley’s subjective idealism, his infamous theory that the world is in our minds).

18th-century thinker Immanuel Kant, meanwhile, attempted to rescue the reality beyond our experience, but in doing so suggested we can never actually know anything about it.

There cannot be an ‘object’ without a ‘subject’, Kant argued: the two are co-dependent. Take the subject away, and it becomes incoherent to even discuss distinct objects, for a subject is required to make such distinctions in the first place.

It follows, Kant concluded, that objects by themselves are unknowable. Time, space, causation — these are features of the subject/object interaction. We cannot know what they are like ‘in themselves’, because we can never strip the ‘subject’ (us) from the world.

So, it’s not just whether the falling tree makes a sound that's in question; without a subject in the story, without a conscious being, the coherence of trees, air, and time and space themselves totally breaks down...

(You can learn more about Kant’s position, which influenced Einstein and many of the early 20th-century’s famous quantum physicists, in my philosophy break on Kant’s transcendental idealism).

But to conclude this brief reflection on the tension between perception and reality, consider a comment from the Nobel Prize-winning quantum physicist Max Planck in a 1931 interview (italics added):

I regard consciousness as fundamental. I regard matter as derivative from consciousness. We cannot get behind consciousness. Everything that we talk about, everything that we regard as existing, postulates consciousness.

What do you think? Can we get behind consciousness?

This is a short exploration of themes covered in my short introduction to philosophy course, Life’s Big Questions, which consists of 42 concise, self-paced lessons on the great philosophers’ best answers to life’s big questions:

Life’s Big Questions: Your Concise Guide to Philosophy’s Most Important Wisdom

From why anything exists to how we should live, unlock philosophy’s best answers to life’s big questions.

Get Instant Access★★★★★ (100+ reviews for our courses)

About the Author

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 20,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (100+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Take Another Break

Each break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your philosophical curiosity.