Nietzsche On What ‘Finding Yourself’ Actually Means

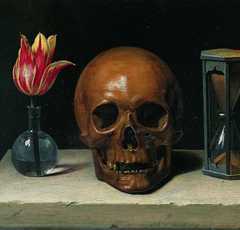

For 19th-century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, our ‘true selves’ are not hidden within us: they are something ever above us, something we must actively work towards. Here’s his sage advice for how we can authentically ‘become’ ourselves.

The great Roman Stoic philosopher Epictetus once wrote, “Don’t explain your philosophy. Embody it.” That’s all well and good, we might think — but how do I know what my philosophy is?

How can I tell which values I affirm? How can I be sure that what I want is what I actually want, not just what I think other people want of me?

In other words: if I’m feeling a bit restless about who I really am, how do I ‘find’ or ‘discover’ myself or my values?

Nietzsche offers a sage answer to these questions in the Schopenhauer as Educator essay of his Untimely Meditations, written in 1874:

This is the most effective way: to let the youthful soul look back on life with the question, ‘What have you up to now truly loved, what has drawn your soul upward, mastered it and blessed it too?’ Set up these things that you have honored before yourself, and, maybe, they will show you, in their being and their order, a law which is the fundamental law of your own self. Compare these objects, consider how one completes and broadens and transcends and explains another, how they form a ladder on which you have all the time been climbing to yourself: for your true being lies not deeply hidden within you, but an infinite height above you, or at least above that which you commonly take to be yourself.

Nietzsche reminds us that authenticity is not hidden within us fully formed, rather our ‘true being’ is something that lies above us, beyond where we currently are.

We thus do not ‘find’ ourselves; we harness our raw materials to create ourselves.

One way to frame this is to view our lives as an artistic project. We begin as a unique, half-formed canvas, receiving color washes from the cultural norms we inherit. The task of life is then to style this canvas into something beautiful, perhaps going beyond the cultural palette we’re familiar with. Every brushstroke contributes towards the finished piece; every choice we make shapes who we are.

Nietzsche asks, what have you “up to now truly loved, what has drawn your soul upward, mastered it and blessed it too?”

We should focus on these, and shape ourselves around them — let our loves and passions create a work of art to which we’d proudly assign our names.

Authentically creating ourselves

In his 1882 work The Gay Science, Nietzsche further discusses how we might go about creating or ‘styling’ our characters according to our own tastes:

To ‘give style’ to one’s character — a great and rare art! It is practiced by those who survey all the strengths and weaknesses that their nature has to offer and then fit them into an artistic plan until each appears as art and reason and even weaknesses delight the eye. Here a great mass of second nature has been added; there a piece of first nature removed — both times through long practice and daily work at it. Here the ugly that could not be removed is concealed; there it is reinterpreted into sublimity. Much that is vague and resisted shaping has been saved and employed for distant views — it is supposed to beckon towards the remote and immense.

With work, we can shape ourselves into something beautiful — where we use even what we regard to be the ugly, undesirable, unchangeable parts of ourselves to lend intrigue, mystique, depth according to a particular “artistic plan.” As Nietzsche finishes the passage:

In the end, when the work is complete, it becomes clear how it was the force of a single taste that ruled and shaped everything great and small…

For, Nietzsche suggests, it is by living up to an independent, authentic aesthetic, rather than to an external ‘ethical’ standard or value system, that humans can truly fulfill their potential.

As he famously declares in his 1872 work, The Birth of Tragedy:

It is only as an aesthetic phenomenon that existence and the world are eternally justified.

After all, he writes in Untimely Meditations:

At bottom every human being knows well enough that he is a unique being, only once on this earth; and by no extraordinary chance will such a marvelously picturesque piece of diversity in unity ever be put together a second time.

As platitudinous as it may sound, there is no one else capable of being what you might become. You thus owe it to yourself, Nietzsche thinks, to become the best, fullest, most empowered version of yourself you possibly can. He writes:

Nobody can build you the bridge over which you must cross the river of life, nobody but you alone. True, there are countless paths and bridges and demigods that would like to carry you across the river, but only at the price of yourself; you would pledge yourself and lose it. In this world there is one unique path which no one but you may walk. Where does it lead? Do not ask; take it.

Many disagree with Nietzsche’s championing of the ‘aesthetic’ over the ‘ethic’, but it is certainly one way to think about authenticity: clarify what you love, on where your true power lies, and focus all your energies on shaping it into something beautiful, reaching upward and beyond where you currently reside.

What do you make of Nietzsche’s advice?

- Do you think Nietzsche offers a good way to think about how we might ‘create’ ourselves and our values?

- Is viewing life as an artistic project — in which we perpetually style and restyle ourselves — helpful?

- Is prioritizing the well-being of others more important than this kind of restless self-making?

- Is there a way of reconciling the two?

Learn more about Nietzsche’s philosophy

If you’re interested in learning more about his philosophy, consider exploring my reading list outlining Nietzsche’s best books. You might also like the following related reads:

- Friedrich Nietzsche’s Life, Insanity, and Legacy

- God is Dead: Nietzsche’s Most Famous Statement Explained

- Eternal Recurrence: What Did Nietzsche Really Mean?

- Übermensch Explained: the Meaning of Nietzsche’s ‘Superman’

- Amor Fati: the Stoics’ and Nietzsche’s Different Takes on Loving Fate

- Ruth Chang on Making Difficult Life Decisions

- Galen Strawson: Our Lives Are Not Stories

- The Apollonian and Dionysian: Nietzsche On Art and the Psyche

- Nietzsche’s Perspectivism: What Does ‘Objective Truth’ Really Mean?

- Introduction to Nietzsche: Your Myth-Busting Guide to His 5 Greatest Ideas

Finally, if you enjoyed this article, you might like my free Sunday breakdown. I distill one piece of wisdom from philosophy each week; you get the summary delivered straight to your email inbox, and are invited to share your view. Consider joining 25,000+ subscribers and signing up below:

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying my free Sunday Breakdown

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox.

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

About the Author

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (100+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Take Another Break

Each break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your philosophical curiosity.