Nietzsche On Why Suffering is Necessary for Greatness

While philosophies like Buddhism and Stoicism operate under the assumption that suffering should be lessened or transcended, Nietzsche thinks suffering can have real value. In fact, greatness is not possible without suffering.

Many philosophies operate under the assumption that suffering is bad. The ultimate goal for Buddhism, for instance, as made clear by the Buddha’s parable of the poisoned arrow, is the cessation of personal suffering through acceptance and enlightenment. The Stoics, meanwhile, seek to eradicate suffering from our lives through rationalization — particularly the dichotomy of control.

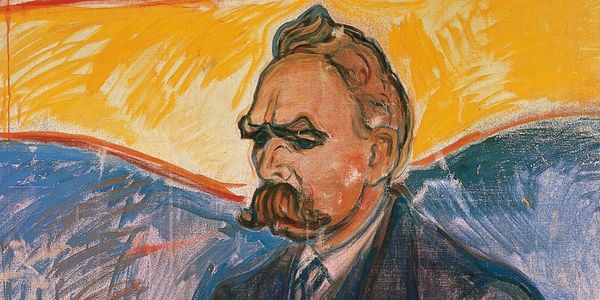

19th-century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, however, thinks such approaches are wrongheaded: we should reconcile ourselves to suffering not by viewing it as something to transcend, nor as a mistake that can be corrected, but by affirming it as a necessary, indispensable part of a full life.

Indeed, while the Stoics seek to purge us of ‘irrational’ pain, and the Buddha wants us to escape the cycle of craving and desire (and thus eventually escape suffering), Nietzsche thinks suffering can be viewed as an authentic, understandable response to life in a world without order or purpose.

In fact, greatness is not possible without suffering. In his 1882 work The Gay Science, Nietzsche writes:

Examine the lives of the best and most fruitful people and peoples and ask yourselves whether a tree that is supposed to grow to a proud height can dispense with bad weather and storms; whether misfortune and external resistance, some kinds of hatred, jealousy, stubbornness, mistrust, hardness, avarice, and violence do not belong among the favorable conditions without which any great growth even of virtue is scarcely possible.

Reflecting on the role suffering has played in his own life, Nietzsche writes in Nietzsche contra Wagner:

As far as my long infirmity is concerned, isn’t it the case that I am unspeakably more indebted to it than I am to my health? I owe a higher health to it […] I owe my philosophy to it as well.

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox:

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

If there are things in our lives that we value, then Nietzsche wants us to realize that we cannot value those things without also valuing everything that brought them about. In his notebooks, he writes:

Suppose that we said yes to a single moment, then we have not only said yes to ourselves, but to the whole of existence. For nothing stands alone, either in ourselves or in things; and if our soul did but once vibrate and resound with a chord of happiness, then all of eternity was necessary to bring forth this one occurrence—and in this single moment when we said yes, all of eternity was embraced, redeemed, justified and affirmed.

Happiness does not exist in isolation; greatness cannot occur without suffering. If we are to affirm life, we must affirm all of it — warts and all. In The Gay Science, he writes:

Only great pain is the ultimate liberator of the spirit…. I doubt that such pain makes us ‘better’; but I know that it makes us more profound.

Though not exactly enjoyable, suffering thus imbues us with a kind of tragic wisdom.

Perhaps the real measure of a person, Nietzsche goes on to suggest, is the amount of truth they can withstand. As he puts it in Ecce Homo:

My formula for greatness in a human being is amor fati: that one wants nothing to be different, not forward, not backward, not in all eternity. Not merely bear what is necessary, still less conceal it… but love it.

Nietzsche develops these ideas further in his doctrine of the eternal recurrence, whereby he challenges us to live in such a way that we would wish to live the same life over and over again. Every heartbreak, every joy, every long day of boredom: in sequence, over and over again.

Only when we can say ‘yes’ to the eternal recurrence can we truly meet the challenge posed by Nietzsche’s amor fati.

What do you make of Nietzsche’s approach to suffering?

- Is suffering always bad?

- Can suffering have value?

- Does the value of Nietzsche’s ‘tragic wisdom’ really outweigh the pain it requires to attain it?

- While he distances himself from Buddhism, is Nietzsche’s approach of radical acceptance and affirmation really so different to the Buddha’s goal of transcendence?

Learn more about Nietzsche’s philosophy

If you’re interested in learning more about Nietzsche, then consider exploring my popular self-paced Introduction to Nietzsche course (join 500+ active members inside).

You might also like the following related reads:

- Friedrich Nietzsche’s Life, Insanity, and Legacy

- God is Dead: Nietzsche’s Most Famous Statement Explained

- James Baldwin: Suffering Can Become a Force for Good

- Eternal Recurrence: What Did Nietzsche Really Mean?

- Übermensch Explained: the Meaning of Nietzsche’s ‘Superman’

- Amor Fati: the Stoics’ and Nietzsche’s Different Takes on Loving Fate

- The Apollonian and Dionysian: Nietzsche On Art and the Psyche

- Nietzsche’s Perspectivism: What Does ‘Objective Truth’ Really Mean?

- Nietzsche On What ‘Finding Yourself’ Actually Means

- Friedrich Nietzsche: the Best 9 Books to Read

Finally, if you enjoyed this article, you might like my free Sunday breakdown. I distill one piece of wisdom from philosophy each week; you get the summary delivered straight to your email inbox, and are invited to share your view. Consider joining 20,000+ subscribers and signing up below:

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 20,000+ subscribers enjoying my free Sunday Breakdown

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox.

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

About the Author

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 20,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (100+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Take Another Break

Each break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your philosophical curiosity.