Stoicism and Emotion: Don’t Repress Your Feelings, Reframe Them

Despite the modern use of the word ‘stoic’, Stoicism does not tell us to repress our feelings, rather it tells us to use our judgment to accept and reframe them.

When we’re in the grip of an emotion – say, anger – there is nothing we can do to snap ourselves out of it. We are lost to the emotion, and all we can do is wait for it to pass.

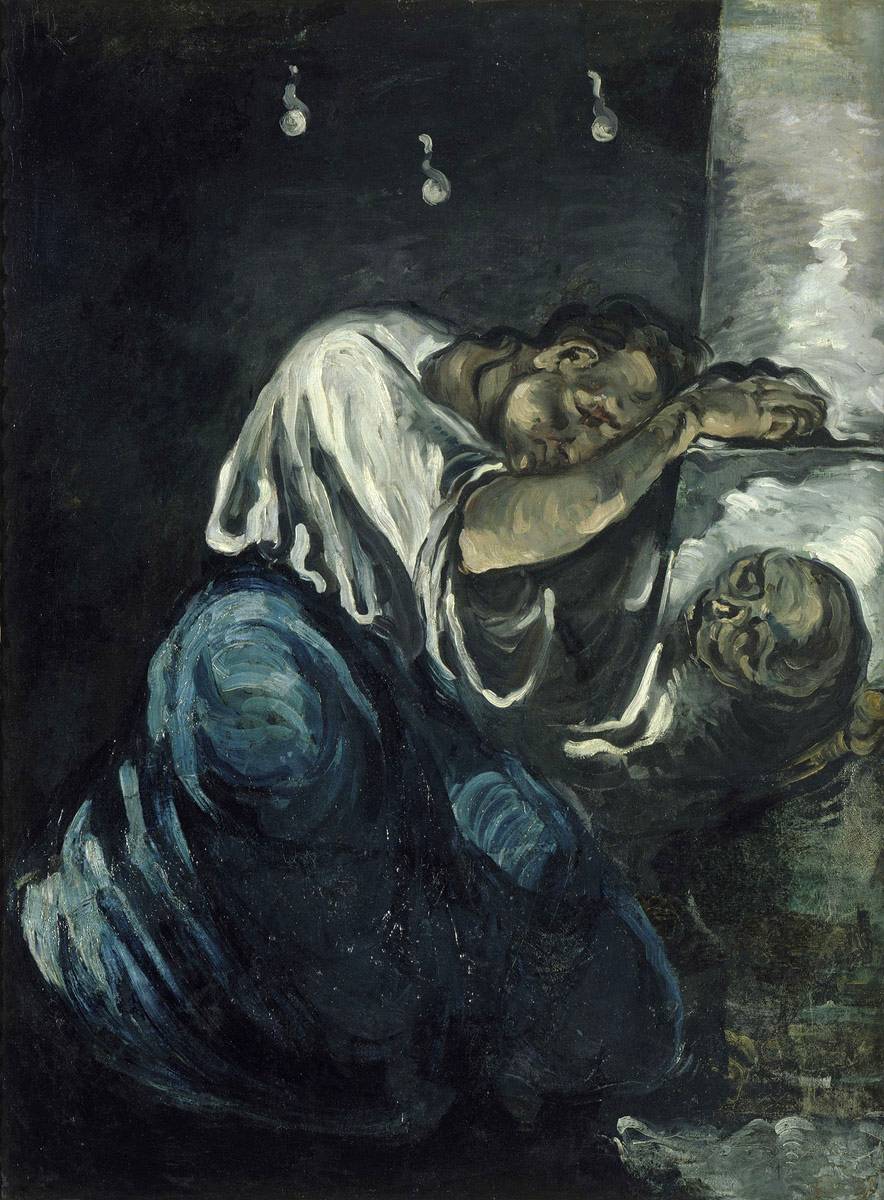

The Stoic philosophers of ancient Greece and Rome knew this well. In his brilliant essay On Anger (which features in Seneca’s Dialogues and Essays), for instance, Seneca describes anger as a temporary madness:

for it is equally devoid of self-control, regardless of decorum, forgetful of kinship, obstinately engrossed in whatever it begins to do, deaf to reason and advice, excited by trifling causes, awkward at perceiving what is true and just, and very like a falling rock which breaks itself to pieces upon the very thing which it crushes.

Given how destructive they find emotions like anger to be, it is no wonder the Stoics have a reputation for seeking to repress them.

However, though commonly thought of as a philosophy that tells us to repress our feelings or emotions in this way – grit your teeth! have a stiff upper lip! – the Stoic view is subtly but importantly different.

The Stoic recommendation is not to repress our emotions, but simply not to have them in the first place.

This might seem like a bizarre recommendation. We are human: how can we not have emotions?

How the Stoics define emotion

It all comes down to how the Stoics define emotion. All of us will experience what Seneca describes as ‘first movements’ in reaction to certain events.

We might feel shocked, excited, jubilant, scared. These are all natural physiological reactions that simply happen to us, and that we have no control over.

Importantly, these are not emotions for the Stoics: they are initial reactions, ‘first movements’.

Emotions are what happen if – via poor judgment – we let these first movements run away from us.

There are thus three stages to the production of emotions:

- First movement

- Judgment

- Emotion

We have no control over the first stage. And, if we reach the third stage, we have no control there either.

The crucial stage is thus the second stage: judgment. We can use our capacity for judgment to either stop a first movement in its tracks, or let our initial reactions gather momentum and become destructive, uncontrollable emotions.

For instance, if we initially react in shock and fear to, say, a spider, but then judge that, actually, while it’s perfectly natural to initially jump in fright, really it’s just a tiny little spider that can’t do us any harm, and fetch a glass to trap and free the little critter outside – taking deep breaths to calm ourselves throughout – then we have successfully slowed the release of adrenaline through our bodies, and halted a ‘first movement’ in its tracks (while demonstrating the cardinal Stoic virtue of courage, well done us).

If however we judge that the fear is justified or even an underreaction – ‘oh my God, it’s a spider and I hate spiders, what am I going to do, I am in serious danger here’ – then the ‘first movement’ gathers momentum – our poor judgment causes our physiological responses to intensify – to become a full-blown emotion of fear, and there is nothing we can do but wait until the emotion passes, acting irrationally and out of control in the meantime.

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying my free Sunday Breakdown

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox.

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

So, the Stoic advice is not that we should avoid ‘first movements’ – doing so would be impossible. The advice is that we work on using our judgment to avoid letting such movements become destructive emotions.

Feeling scared, nervous, annoyed: this is part of what it means to be human.

The idea is that we use our judgment to accept these natural feelings and impulses, and then gently point out to ourselves that we don’t have to let them warp our view of the world, rule our thoughts, or govern our actions (indeed, the only governors of our actions should be the four cardinal Stoic virtues: wisdom, courage, justice, and temperance).

It’s fine to be annoyed by things every now and then, that’s perfectly natural. It becomes an issue if we routinely let our annoyances gather momentum into uncontrollable anger.

This is what mastering our emotions means for the Stoics: not repressing or ignoring our feelings, but using our judgment to wisely add perspective and prevent ourselves from losing control.

And, importantly, the point of retaining control is not just to make ourselves feel better; it’s so that we can move forward constructively, and do the right thing.

As Seneca writes:

An emotion, then, does not consist in being moved by the appearances of things, but in surrendering to them and following up this casual impulse. For if anyone supposes that turning pale, bursting into tears, sexual arousal, deep sighs, flashing eyes, and anything of that sort are a sign of emotion and mental state, he is mistaken and does not understand that these are merely bodily impulses… A man thinks himself injured, wants to be revenged, and then – being dissuaded for some reason – he quickly calms down again. I don’t call this anger, but a mental impulse yielding to reason. Anger is that which overleaps reason and carries it away.

Practicing the Stoic approach to emotion in everyday life

Of course, the Stoics were writing at a time before the physiological underpinnings of conditions like chronic anxiety had been better researched and understood, so their advice – use your judgment to lend perspective to your situation! – may not be sufficient in all cases, and is not a replacement for professional therapeutic care.

Nevertheless, recalling the lessons of Stoicism can still be of real benefit: by attempting to make clearer judgments about our situation, we can protect ourselves from spiraling, destructive emotions, and create room to move forward with virtue.

For instance, say someone insults you. In the moment, you might judge that it is outrageous for that person to injure you so, and so your ‘first movement’ of annoyance may quickly become anger.

The mistake here, the Stoic philosopher Epictetus points out, is thinking that because you’ve received an insult you’ve automatically been injured:

Remember, it is not enough to be hit or insulted to be harmed, you must believe that you are being harmed. If someone succeeds in provoking you, realize that your mind is complicit in the provocation.

You’ve only been injured, Epictetus says, if you choose to decide that you have been. As contemporary philosopher John Sellars clarifies in his short but illuminating book, Lessons in Stoicism (which features in our reading list of Stoicism’s best books):

If someone says something critical about you, stop to consider whether what they say is true or false. If it is true, then they have pointed out a fault that you can now address. As such, they have benefited you. If what they say is false, then they are in error and the only one being harmed is them. Either way, you suffer no harm from their critical remarks.

The lesson here is that we shouldn’t let our impulsive reactions guide our behavior.

If we do so, it is not just a case of poor judgment, it is total lack of judgment: we are going straight from ‘first movement’ to emotion without applying any tempering use of reason whatsoever.

We must therefore ensure we take time to pause and reflect before leaping to action.

We should accept our feelings as they arise; take stock, bring virtue to mind; and then act.

Seneca puts it well when he says “The greatest remedy for anger is delay”, and:

If you want to determine the nature of anything, entrust it to time: when the sea is stormy, you can see nothing clearly.

So: pause, and remember this line from perhaps the most famous Stoic philosopher, Marcus Aurelius (see our reading list of Marcus Aurelius best books here):

You shouldn’t give circumstances the power to rouse anger, for they don’t care at all.

What if we cannot stop our emotions?

What if simply waiting doesn’t ease the strength of our feelings? What about cases of outrageous wrongdoing or injustice to a loved one? What should we do when the force of our feelings threatens to overpower whatever sober judgments we attempt to apply to them, and tip us into uncontrollable emotion?

The recommended Stoic tactic here – if we are simply unable to rationalize the rage of a first movement – is to use our judgment to redirect the force of our feelings into something constructive.

So, in the case of a loved one suffering from wrongdoing, rally your ‘first movement’ of passion under the banner not of anger, but of justice. Let your feelings be led by virtue, not uncontrollable vice.

This way, the destructiveness of negative emotions is less likely to eat you up, for you are operating with a constructive end in mind.

Strive to calmly, passionately do the right thing in the name of justice, rather than lose yourself to a destructive rage.

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox:

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

In summary, then: the Stoics aim to help us deal with destructive emotions by recalling the key lesson of the dichotomy of control: focus on what we can control.

We cannot control our initial reactions to situations, but we can control our judgment of such ‘first movements’.

By training ourselves to pause, reflect, and judge constructively, we can – with practice – stop first movements from gathering momentum, and thus rid ourselves of negative, uncontrollable emotions that have the potential to ruin our lives.

How do the Stoics approach positive emotions?

What about positive emotions like love? Do the Stoics think we should rationalize and temper those, too? The verdict here tends to be that the Stoics are concerned with emotions that have the potential to ruin the tranquility of our lives.

A jealous, possessive love, for example, has life-ruining potential, and should be treated like any other negative emotion; but a compassionate love based on our natural need for companionship is perfectly healthy – we must just be mindful that we hold no unrealistic expectations or false beliefs about it that have the potential to shatter us in future.

For instance, if we falsely believe that the love between us and a parent, partner, or our children will last forever, then – given the fact that we are all mortal – we are in for a nasty surprise.

We thus shouldn’t repress or temper joyful ‘first movements’, but we should be careful that we don’t let them develop into false hopes or beliefs about what the future might hold.

Learn more about the Stoic philosophy of life

As with the Epicurean therapeutic approach to philosophy, the Stoics think the purpose of philosophy is not just conceptual clarification; the purpose of philosophy is to help us live better, more tranquil lives.

The dichotomy of control, and knowing what to do when the world feels broken, are powerful tools in this regard, but the Stoics knew that implementing them in the face of real emotion or profound adversity is a significant challenge.

If you’re interested in learning more about how the Stoics approached not just emotion and adversity but the entirety of life (including living up to the four cardinal virtues and facing up to death, as Seneca discusses in his essay on the shortness of life), you might like our new guide, How to Live a Good Life (According to 7 of the World’s Wisest Philosophies), which compares the wisdom of Stoicism to 6 rival philosophical approaches to life.

In the meantime, what do you make of this analysis? Do the Stoic recommendations around emotion resonate with you? Or do our emotions not need to be so carefully mastered?

How to Live a Good Life (According to 7 of the World’s Wisest Philosophies)

Explore and compare the wisdom of Stoicism, Existentialism, Buddhism and beyond to forever enrich your personal philosophy.

Get Instant Access★★★★★ (100+ reviews for our courses)

About the Author

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (100+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Take Another Break

Each break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your philosophical curiosity.