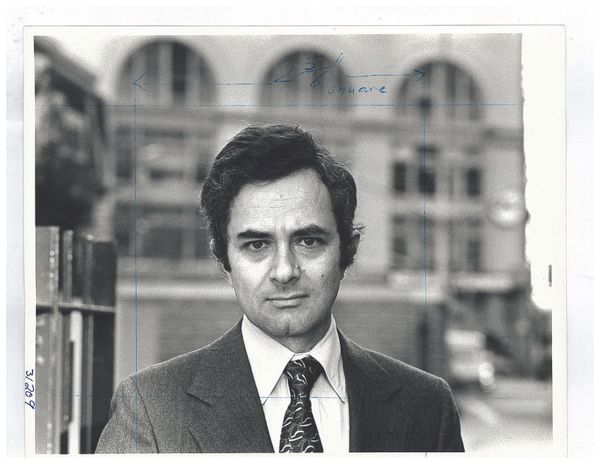

Thomas Nagel On Why Humor is the Best Response to Life's Absurdity

Life is absurd — but that's no reason for despair, argues contemporary philosopher Thomas Nagel. This article discusses why he believes humor to be the best way to cope with being human.

Throughout the history of philosophy, philosophers have been relatively quiet on humor — and the little that has been written has been rather descriptive and surprisingly negative. Plato and Hobbes, for instance, regarded laughter as an expression of superiority — even of scorn. Kant and Schopenhauer, meanwhile, correspond more closely to what is known as ‘Incongruity Theory’ — that laughter is caused by the puncturing of a set up of expectation.

Contemporary American philosopher Thomas Nagel, however, goes beyond theorizing about why we laugh and places humor as the essential stance to adopt in response to being human.

Consider the absurdity of the human condition

Like the existentialists and absurdists of the 20th century, Nagel believes the human condition is ultimately absurd. For Nagel, this absurdity arises not because anything we do won’t matter in, say, a million years. Nor because we are small or insignificant in the eyes of the universe. No: these are inadequate expressions of absurdity.

Rather, Nagel believes our absurd condition arises from a collision between the seriousness with which we take our lives, and our capacity to step back, look at things from a wider perspective, and see how ridiculously contingent the activities that fill our lives really are.

In his 1971 essay The Absurd, Nagel writes:

We step back to find that the whole system of justification and criticism, which controls our choices and supports our claims to rationality, rests on responses and habits that we never question... We see ourselves from outside, and all the contingency and specificity of our aims and pursuits become clear.

“Yet,” he continues, “when we take this view and recognize what we do as arbitrary, it does not disengage us from life, and there lies our absurdity: not in the fact that such an external view can be taken of us, but in the fact that we ourselves can take it, without ceasing to be the persons whose ultimate concerns are so coolly regarded.”

We are consumed by the act of living: we follow careers or chase happiness or cultivate a certain lifestyle. But even in the day-to-day heat of this pursuit, we possess a strange ‘meta’ capacity to step back and recognize the highly specific nature of the rituals we follow, the arbitrariness of the goals we have, knowing our purposes would be very different if our circumstances were different — but continuing to follow and pursue them as if they're all-important anyway.

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 20,000+ subscribers enjoying my free Sunday Breakdown

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox.

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

The inadequate expressions of absurdity mentioned earlier — our insignificance due to small size and short lifespan — are thus revealed to simply be metaphors for this 'meta' perspective: “by feigning a nebula's-eye view,” Nagel explains, “we illustrate the capacity to see ourselves without presuppositions, as arbitrary, idiosyncratic, highly specific occupants of the world, one of countless possible forms of life.”

Compare our existential situation to that of mice, Nagel advises. Like us, mice have to work to stay alive. But unlike us their existences aren’t absurd. This is because mice lack the required capacity for self-consciousness and self-transcendence that would enable them to see that they’re only mice.

If a mouse were to suddenly gain such abilities, Nagel writes, “his life would become absurd, since self-awareness would not make him cease to be a mouse and would not enable him to rise above his mousely strivings. Bringing his new-found self-consciousness with him, he would have to return to his meagre yet frantic life, full of doubts that he was unable to answer, but also full of purposes that he was unable to abandon.”

What really makes life absurd? How Nagel differs from Camus

Nagel’s conception of absurdity — that we take our lives seriously despite recognizing their contingency — subtly differs from the better-known account put forward by the cool chief of absurdism, French philosopher Albert Camus.

Camus states the absurdity of the human condition arises from our need for meaning in a meaningless world. But for Nagel this doesn’t quite hit the mark. Absurdity arises not from our relationship to the world, he thinks, but from our human capacity to step back and adopt a universe-eye view of our existence. As he clarifies:

Camus maintains that the absurd arises because the world fails to meet our demands for meaning. This suggests that the world might satisfy those demands if it were different. But now we can see that this is not the case. There does not appear to be any conceivable world (containing us) about which unsettleable doubts could not arise. Consequently the absurdity of our situation derives not from a collision between our expectations and the world, but from a collision within ourselves.

What should we do in the face of absurdity?

As well as differing to Camus in his conception of the absurd, Nagel also differs in his recommended response to it. While both agree that life’s absurdity cannot be escaped — that we must simply live with it — Camus recommends a stance of defiance to help us cope, which Nagel questions:

Camus rejects suicide and the other solutions he regards as escapist. What he recommends is defiance or scorn. We can salvage our dignity, he appears to believe, by shaking a fist at the world which is deaf to our pleas, and continuing to live in spite of it. This will not make our lives un-absurd, but it will lend them a certain nobility. This seems to me romantic and slightly self-pitying.

For Nagel, “our absurdity warrants neither that much distress nor that much defiance.” Instead, we should recognize absurdity not as a demand for heroism but rather as a “manifestation of our most advanced and interesting characteristics”, arising from our incredible human ability for self-transcendence.

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox:

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

Indeed, if our sense of the absurd arises as a result of our advanced capability to perceive our true situation in the universe, then what possible reason can we have to resent or escape it? As Nagel concludes:

It need not be a matter for agony unless we make it so. Nor need it evoke a defiant contempt of fate that allows us to feel brave or proud. Such dramatics, even if carried on in private, betray a failure to appreciate the cosmic unimportance of the situation. If sub specie aeternitatis there is no reason to believe that anything matters, then that doesn't matter either, and we can approach our absurd lives with irony instead of heroism or despair.

Laughing together in the dark

When we step back and see our strivings for what they are — highly specific and without any real universal meaning — the view for Nagel is not heroic nor hopeless, but, as he puts it earlier in his essay, “sobering and comical”.

We are self-aware mice unable to rise above our mousely strivings, and we continue to strive regardless. Does this ironic situation really call for despair? There's no real need for such dramatics, Nagel thinks. To paraphrase Oscar Wilde's quip in the comedy Lady Windermere’s Fan — life is much too important to be taken seriously. The appropriate response to the human condition is a slightly bemused smile — a celebratory laugh that we understand life's absurdity, yet carry on regardless.

In summary, then — yes, life is absurd. But hey! — it's interesting, and we can help each other through it by championing our enlightened cognitive condition with an ironical, humorous stance, and let our amused fascination light up the dark.

Further reading

If Nagel’s position on absurdity has stoked your amused fascination for life, his book What Does It All Mean? is his brilliant introduction to the questions that have occupied philosophers for millennia.

If you’re looking for something a bit more controversial, Nagel’s 2012 Mind and Cosmos will provoke your thoughts on subjects ranging from evolution to the emergence of consciousness. Highly criticized when first published, Nagel’s book challenges the dominant materialist conception of the universe — and will challenge assumptions you may or may not be aware of making.

If that doesn’t float your boat, check out our reading list of the most recommended introductory books to all things philosophy by hitting the banner below now.

An Introduction to Philosophy

The Top 5 Books to Read

About the Author

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 20,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (100+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Take Another Break

Each break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your philosophical curiosity.