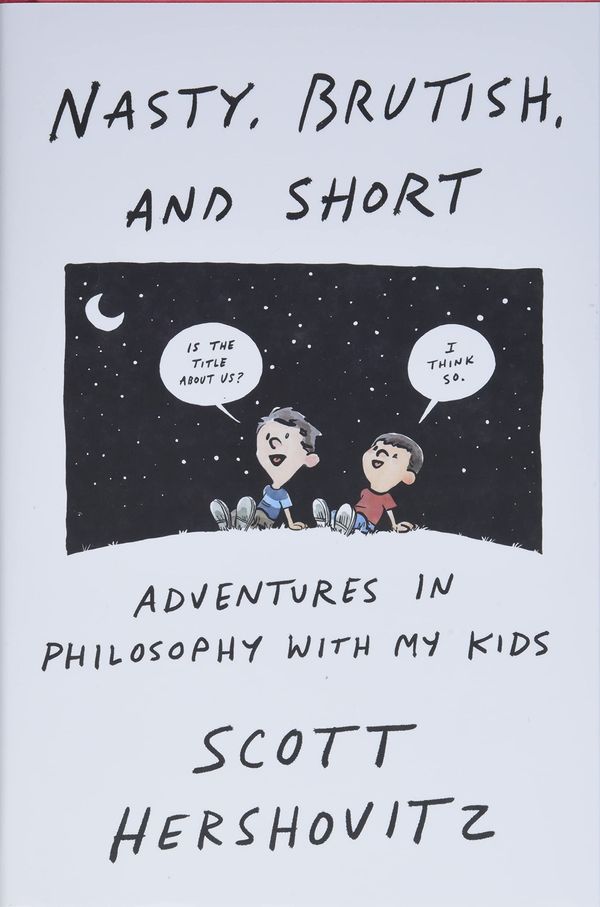

Nasty, Brutish, and Short: Adventures in Philosophy with My Kids

BY SCOTT HERSHOVITZ

We spoke to philosophy professor Scott Hershovitz about why children make great philosophers, as discussed in his new book, Nasty, Brutish, and Short: Adventures in Philosophy with My Kids.

Scott Hershovitz is the Thomas G. and Mabel Long Professor of Law and Professor of Philosophy at the University of Michigan. His academic work focuses on law and philosophy, and has appeared in the Harvard Law Review, The Yale Law Journal, and Ethics, among other places.

We caught up with Scott about his new book, Nasty, Brutish, and Short: Adventures in Philosophy with My Kids, which offers an incredibly entertaining and informative introduction to philosophy through conversations Scott has with his two young sons, Rex and Hank.

Together, Scott, Rex, and Hank explore classic and contemporary philosophy, discussing questions like, how does Hank know he’s not dreaming all the time? Does Scott have authority over Rex and Hank? Is the red Rex sees the same as the red everyone else sees? When is it okay to swear? And, does the number six exist? Scott seeks to demonstrate that, ultimately, we shouldn’t just encourage children in their boundless questioning about existence: we should join them, so that we can rekindle our own curiosity about the world.

So the idea came in stages, actually. Shortly after I had kids, I realized I was talking about them a lot to my students in class. If we were discussing punishment, for example, I’d describe something one of my kids had done and ask my students how they thought I should respond. It was a way of getting a conversation going about the purposes of punishment, without necessarily diving straight into the abstract philosophy I’d prepared for the day.

I teach my students about the philosophy of law and authority. And my kids are challenging my authority all the time. When he was around three years old, for instance, my older son, Rex, picked up “you’re not the boss of me.” And I thought, well, actually, I kind of am... But I put that question to my class: am I his boss? If so, why? And then we eventually transition to thinking about authority among adults or in the legal system.

So, for years, it was just part of my stock of teaching tricks. But I never really thought about writing a book until I was out at the University of California, Irvine. There’s a philosopher there named Aaron James who wrote a popular book a while ago called Assholes: A Theory. I was out at UC Irvine giving a paper, and I met Aaron and a few others for dinner. I was having trouble getting people to see a particular point I was making, and so I told them a story about my little one, Hank, and about arguments we’ve had about the rules in our house.

As I finished telling that story, two things happened. One is that everyone at the table understood what I was saying, and the second was that Aaron leaned over and said, “that’s your book.”

So Aaron provided a huge assist, and ever since he said that I was thinking, “how can I make this happen?” And I eventually got connected to an agent and took all these stories that I use for teaching and put them in a book for a bigger audience.

I think it’s a couple of things. Firstly, they don’t know a lot about the world: they’re just really puzzled by it. And part of not knowing about the world is not knowing what other people take for granted, or what the standard explanations of things are. They’re constantly seeing things and wondering, for example, why someone gets to tell them what to do, or how big the universe is — whatever it is that pops into their head, they’re curious about it and thinking it through.

And then I think the second thing is they’re just fearless as thinkers, for a variety of reasons. They’re not afraid about being wrong — they’re wrong all the time — and it’s not embarrassing to them that they’re wrong.

I think there’s this sweet spot for kids, before they are really focused on what other people think of them, when they’re just really willing to share their ideas and questions.

An example in the book is Rex’s argument, when he was seven, about how big the universe is. He argues it must be infinite, because if it was finite, what would happen if he traveled to the edge? Rex suggests if he punches the edge, he’d either punch through it, meaning there’s no edge after all, or something would stop his punch, meaning — again — that there is something beyond the apparent edge.

I think if he thought of that argument when he was older, not even that much older, say when he was thirteen rather than seven, he wouldn’t have been so forthcoming with it. Self-consciousness may have held him back: “what makes you think you can figure out how big the universe is?” So, I think there’s this sweet spot for kids, before they are really focused on what other people think of them, when they’re just really willing to share their ideas and questions.

That is maybe my favorite question in the book, actually. It was recorded by Gareth Matthews, a philosopher who dedicated most of his career to kids.

The point is that the child who asked that question, Ian, hasn’t yet been acculturated in the way we make decisions, so this is the first time he’s encountered the idea that if more people want something, that makes it the right or fair thing to do. His question is a challenge to certain economic ways of thinking about the world, i.e. that we should just be trying to maximize the satisfaction of people’s preferences. It’s also a challenge to democracy in a really interesting way: if people are voting for their selfish interests, why is that a good way of making decisions?

Ian’s is a fantastic question and is typical of the kind that children ask seemingly effortlessly in ways that undermine our social practices. Once you have an eye out for these kinds of inquiries, you’ll start noticing kids saying all sorts of philosophically interesting things just with their casual comments and queries.

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox.

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

I think for a few reasons. One is often they don’t know the answers. I think grown ups are a little bit uncomfortable when they don’t know the answer to kids’ questions — and that’s any question, not just philosophical questions.

I think what a lot of adults are missing is that philosophy can be fun because you don’t know the answer.

I remember before my wife and I had kids, a philosophy professor at UCLA, Mark Greenberg, came to visit us along with his wife and daughter. Mark’s daughter asked him a question about some steam coming out of a grate, and Mark actually knew the answer. What I was so struck by, because I hadn’t spent a lot of time around parents or kids, is that he gave a complete scientific answer — he explained exactly where the water vapor was coming from and why it looked the way it did. And I thought, how cool is that? He just treated her like a grown up who didn’t know the explanation, and he gave this girl who was probably three or four at the time the complete answer. And I thought if I have kids, I’m going to do that.

You realize, of course, that you’re limited in your ability. And sometimes you have to say things like “I don’t know” or “here’s a guess. Maybe we’ll go look it up.” But I think what a lot of adults are missing is that philosophy can be fun because you don’t know the answer.

This is a point that Gareth Mathews makes: that most conversations between adults and kids are hierarchical, where adults tell kids the answer; whereas in philosophy, it’s much easier to say, “Hey, I don't know, what do you think?” And then have a collaborative conversation about it.

That’s right. They’re pleased to have you take their views seriously and that you’re interested in what they have to say... I suppose another reason adults may find it uncomfortable when kids ask philosophical questions, if we think back to Ian’s question about selfishness, is that sometimes within the question is a challenge to the adults, an implicit criticism that they’ve made a mistake, and that can make the questions not so well received.

I mean, I’m pretty indulgent, as you can tell by the book. But one piece of advice I have for folks is if you don’t have time or you’re just too frazzled in the moment, just return to the question later. The most fruitful time in our family to have conversations, for example, is at bedtime, as the kids are trying to extend the time before the lights go out. It’s also quiet and peaceful and you can say, hey, earlier you asked about this, you’re wondering about that, or this happened… so I try to come back to the questions if I don’t have time to deal with them in the moment.

I think she’s more amused than impatient, though I suspect sometimes she might be a little impatient, too! When Rex and Hank first came along, she sometimes commented that she never would have thought to talk to them about, say, infinity, authority, or whether the universe is a simulation — but there’s certainly no tension between us on that.

I think there’s a few reasons. Maybe it’s just the kind of philosopher I am, but I’m committed to thinking having philosophical conversations with your kids is a fun, worthwhile activity that doesn’t have to be instrumentally valuable. So that’s part of what I want to say to parents: your kids are really smart and deep thinkers, and you should appreciate them as they are, not just think of them as a project or runway to someplace else. So partly I just want to say: enjoy this aspect of your kid, and you’ll have fun, too.

I also hope that by encouraging kids to really think deeply and carefully about things — and be open to questioning things — that they can carry such an attitude into adulthood.

And, to the extent that kids may close down a little bit because they think other people aren’t interested in their ideas, by having these thoughtful conversations with your kids maybe you can help them recognize that their ideas are valuable, and that thinking philosophically is a valuable activity.

I don’t think there’s any topics entirely off limits, but you might want to change the way you talk about certain things. From the time kids hear about death, there are going to be lots of questions about death. And we want our kids to be aware in general terms of what’s going on. So, for example, we’ve had conversations about the war, about the killings of civilians in the war, about police brutality in the States, but we don’t then go ahead and turn on the news and show them videos of that.

I think it’s not about being selective with topics, it’s more about being selective with the imagery and ideas you put in their heads around those topics.

I’m still thinking about that, actually. And if you asked me parts of the book where I’m a little uncertain about what I said, this part is one of them. And that’s because in the States, we have a real problem with some media sources that are just relentlessly ideological and present false narratives about the world. And I don’t want to hide that fact from my kids, but I also don’t want to impose my own judgments on them.

So, I suggest a set of questions, such as: are these real journalists? If these people discovered they were wrong, do I trust them to tell me? Do they issue corrections?

I want to teach my kids that when you encounter news stories, here’s a way in which you go about evaluating their credibility. But, with that, the way the balance is struck is to make it clear to them that the mere fact that someone disagrees with you, or has a viewpoint different to yours, is not evidence that they’re wrong.

There are a number of different buckets here. Maybe first and foremost, I think parents of young kids will get a lot out of the book. They may see their own kids in it and learn new ways of talking to their kids. And beyond parents there’s grandparents, teachers, and really anybody that spends time with young kids.

But I hope the book can find a broader audience than that, because as I mentioned earlier, people just light up when you talk about kids. Kids are fun, they’re funny, and they make these questions accessible. And so I wrote the book in the hope that it would be a fun introduction to philosophy for anybody who’s new to the field.

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

I also hope that the book is doing enough new along the way that people who were, say, philosophy majors or have a general interest in philosophy and want to revisit it will find some things that are familiar and some things that are new to think about. The book was quite consciously twelve chapters in length to mirror the kind of thing you could spread out over the course of a semester at university, or maybe even secondary school.

I am completely behind that. I think there are lots of benefits, some of which we’ve already spoken about — like raising kids who are willing to challenge things, to question assumptions, to think deeply and carefully about the world, and so on.

But I also think that what you see through the existing programs of philosophy in schools is they’re teaching kids additional skills about how to disagree agreeably: how to have calm conversations with each other about difficult issues.

My hope would be if this kind of philosophical discussion was a more regular part of our education, then we could have a culture that thought deeper and was more respectful, rather than one side shouting at the other.

For example, I just taught a class to my law students, an older group of course, but it was called Life, Death, Love and the Law. It was about ethical issues that arise at the beginning and end of life, ethical issues about whether you should have kids, ethical questions about abortion, ethical questions about euthanasia. The students in my class had a really wide range of backgrounds — different religious upbringings, different political views, so there were lots of different perspectives in the room on these questions.

We set a tone early on: we’re going to question each other’s views, we’re going to question our own views, we’re going to be respectful of each other and the fact that many people in the room have personal experience of these issues. If you’re not up for a really deep interrogation of these issues, then you don’t have to be here. You can drop this class. There’s no point in being in this room.

The semester was phenomenal. People who on the one side, for instance, may have felt that abortion is a kind of murder, and people on the other side who thought that equality absolutely demands the right to terminate a pregnancy — these people had really thoughtful discussions with each other and came to better understand each other’s views.

My hope would be if this kind of philosophical discussion was a more regular part of our education, then we could have a culture that thought deeper and was more respectful, rather than one side shouting at the other.

Maybe that’s a bit of a pipe dream, but if I can ask you questions or criticize your view without shouting you down, if I can respect that given you’re a person in the world, it’s worth trying to understand how you came to have your view, then maybe I’ll learn something. Maybe I’ll discover that I’m wrong; maybe I’ll spot reasons I think you’re wrong and share them with you, calmly and respectfully. If we could get in the practice of doing that more regularly, we’d be in a better place, I think.

You can order Scott’s new book Nasty, Brutish, and Short: Adventures in Philosophy with My Kids here, or simply hit the banner below.

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (100+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Each break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your philosophical curiosity.