Amor Fati: the Stoics’ and Nietzsche’s Different Takes on Loving Fate

Amor fati is a Latin phrase meaning ‘love of fate’, an idea rooted in the ancient Greco-Roman philosophy of Stoicism. In critiquing Stoicism and developing his own take on amor fati, Nietzsche eloquently discusses how transformative the idea can be.

Amor fati is a Latin phrase that literally means love of fate. Put simply, this means anyone practicing amor fati would embrace whatever befalls them. Winning the lottery, losing a job, losing a limb — all would be met in the same unperturbed spirit of amor fati.

This might bring to mind the ancient Greco-Roman philosophy of Stoicism, for the idea has deep resonance with a number of core Stoic principles.

For example, with his dichotomy of control, the Stoic philosopher Epictetus suggests we should focus only on what we can personally influence, and learn to embrace all else. As he advises in The Art of Living:

Happiness and freedom begin with a clear understanding of one principle: some things are within our control, and some things are not. It is only after you have faced up to this fundamental rule and learned to distinguish between what you can and can’t control that inner tranquility and outer effectiveness become possible.

Rather than fight against things we are powerless to change, Epictetus suggests we adjust our mindset to accept things as they are:

Don’t seek that all that comes about should come about as you wish, but wish that everything that comes about should come about just as it does.

In his Meditations, the great Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius describes a happy, virtuous individual in similar terms:

[H]e loves and welcomes whatever happens to him and whatever his fate may bring.

Nietzsche’s eloquent discussions of amor fati

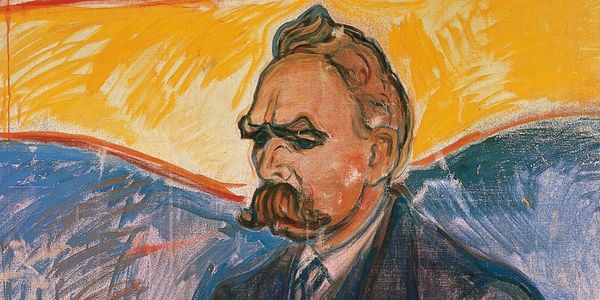

While the idea conveyed by amor fati is discussed by the Stoics, the Latin phrase itself gained traction thanks to its use by the 19th-century German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche.

In his 1882 work The Gay Science, for instance, Nietzsche writes:

I want to learn more and more to see as beautiful what is necessary in things; then I shall be one of those who makes things beautiful. Amor fati: let that be my love henceforth! I do not want to wage war against what is ugly. I do not want to accuse; I do not even want to accuse those who accuse. Looking away shall be my only negation. And all in all and on the whole: some day I wish to be only a Yes-sayer.

Then, in his 1888 Ecce Homo, Nietzsche writes:

My formula for greatness in a human being is amor fati: that one wants nothing to be different, not forward, not backward, not in all eternity. Not merely bear what is necessary, still less conceal it… but love it.

How are we supposed to embrace terrible events?

One immediate reaction we might have to amor fati is wondering how the idea can possibly apply in the face of terrible events.

Sure, we can say ‘yes’ to the world when the world says ‘yes’ to us — but what about people who live with constant pain, or who are stuck in a war zone? Are they supposed to ‘love’ their fate?

Well, it’s important to note that neither the Stoics nor Nietzsche take the consequences of amor fati lightly. This is not an idea that sprang from luxury; in fact, it’s an idea very much designed for coping with hardship.

The three great Roman Stoics — Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius — did not have easy lives:

- Seneca (4 BCE - 65 CE) was adviser to the Roman Emperor Nero, and was eventually exiled and forced to take his own life.

- Epictetus (50 CE - 135 CE) was a slave who gained his freedom.

- Marcus Aurelius (121 CE - 180 CE) was Emperor of Rome during a time of constant crisis, be it war or plague, and most of his children died before he did.

Nietzsche, meanwhile (as I discuss in my article on Nietzsche’s life, insanity, and legacy), suffered enormously throughout his lifetime — chronic pain, rejection, loneliness, and isolation were the hallmarks of his day-to-day existence.

That these philosophers lived through war, enslavement, immense pain, the death of loved ones, yet still advocated amor fati is testament to their belief in the idea’s power.

But to really understand why the Stoics and Nietzsche recommend amor fati, we must first consider the context of their broader philosophical systems.

And, once we do so, we’ll see how their conceptions of the provocative idea are actually rather different.

What’s the difference between the Stoics’ and Nietzsche’s conceptions of amor fati?

While the Stoics and Nietzsche may seem aligned on amor fati, their agreement is superficial, for they actually interpret a key part of the equation — fate — in diametrically opposed ways.

For the Stoics, the cosmos is rationally ordered according to a divine providence. When we embrace fate on these terms, we are thus embracing something that is purposeful and rationally ordered — something beyond us, something wiser, something divine.

There is thus a level of optimism to be found in the Stoics’ embracing of fate: ultimately, we are in the hands of rationally ordered Nature, and should align our judgments about what happens to us accordingly.

Nietzsche’s conception of the cosmos, meanwhile, is rooted in the Heraclitan picture of eternal chaotic flux: the cosmos is not rational or purposeful, it’s disordered and purposeless. There is no grand teleology to comfort us: there is just the endless, tumultuous flux of existence.

Embracing fate on these terms is an entirely different proposition: for Nietzsche, amor fati means acknowledging the chaotic purposelessness of existence, yet affirming it anyway.

Nietzsche thus rejects the optimistic teleology of Stoicism, and in doing so makes the idea of amor fati significantly more challenging.

We are not reconciling ourselves to some grand Stoic purpose, ‘God’s plan’, or such platitudes as ‘everything happens for a reason’. Rather, Nietzsche is asking us to acknowledge that everything happens for no reason, that the cosmos has no purpose — and to love our lives all the same.

How the Stoics and Nietzsche respond to suffering

The difference between the Stoics’ and Neitzsche’s conceptions of amor fati really comes out when we consider how they might each reconcile ‘loving our fate’ with an event that causes significant pain, like the untimely death of a loved one.

The Stoics, for instance, would remind us that the mental anguish we are experiencing is a result of our judgment of the situation, not the situation itself: it is our false, irrational belief about the event, not the event itself, that hurts us.

Relieving ourselves of suffering thus means correcting our false beliefs, purging ourselves of irrational passions, and seeing our situation rationally and clearly.

In the context of death, this means recognizing we are all part of the Stoics’ rationally ordered Nature, and that mortality is inescapable.

Existence, Epictetus tells us, is a temporary gift. Addressing the cosmos directly, he declares:

Now you want me to leave the fair, so I go, feeling nothing but gratitude for having been allowed to share with you in the celebration.

Life is an event, and like all events it must come to an end. The time we’ve each been given, then, is a gift from the cosmos that we — and our loved ones, Epictetus warns — must one day return:

Under no circumstances ever say ‘I have lost something,’ only ‘I returned it’. Did a child of yours die? No, it was returned. Your wife died? No, she was returned… You are a fool to want your children, wife, or friends to be immortal; it calls for powers beyond you, and gifts not yours to either own or give.

Of course, adopting such an attitude is easier said than done, and takes many years of thinking like a Stoic to exert such rational control over our judgments.

But, ultimately, the Stoic approach to suffering follows this course: we should rationally reframe our judgments until the (irrational) suffering is dissolved. (For more here, see my article on Stoicism and emotion).

Amor fati for the Stoics thus means yielding (and aligning our judgments) to the rational order of Nature.

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox:

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

Nietzsche: suffering plays an indispensable role

Nietzsche, by contrast, rejects the optimistic teleology of Stoicism. In an early series of lectures he gave as a young professor on the pre-Platonic philosophers, Nietzsche discusses how the Stoic picture of the cosmos develops that put forward by Heraclitus, stating in unfavorable terms that:

the Stoics re-interpreted [Heraclitus] on a shallow level, dragging down his basically aesthetic perception of cosmic play to signify a vulgar consideration for the world’s useful ends, especially those which benefit the human race. His physics became, in their hands, a crude optimism.

In his 1886 work Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche expands upon this critique by claiming that, while the Stoics claim their philosophy ‘follows from nature’, they first imbue nature with an optimistic teleology. In a substantial but illuminating passage, he writes:

So you want to live ‘according to nature?’ Oh, you noble Stoics, what a fraud is in this phrase! Imagine something like nature, profligate without measure, indifferent without measure, without purpose and regard, without mercy and justice, fertile and barren and uncertain at the same time, think of indifference itself as power—how could you live according to this indifference? Living—isn’t that wanting specifically to be something other than this nature? Isn’t living assessing, preferring, being unfair, being limited, wanting to be different? And assuming your imperative ‘live according to nature’ basically amounts to ‘living according to life’—well how could you not? Why make a principle out of what you yourselves are and must be?—But, in fact, something quite different is going on: while pretending with delight to read the canon of your law in nature, you want the opposite […] Your pride wants to dictate and annex your morals and ideals onto nature […] you demand that it be nature ‘according to the Stoa’ and you want to make all existence exist in your image alone—as a huge eternal glorification and universalization of Stoicism! For all your love of truth, you have forced yourselves so long, so persistently, and with such hypnotic rigidity to have a false, namely Stoic, view of nature, that you can no longer see it any other way,—and some abysmal piece of arrogance finally gives you the madhouse hope that because you know how to tyrannize yourselves—Stoicism is self-tyranny –, nature lets itself be tyrannized as well.

In other words, while the Stoics claim to live ‘according to nature’, really all they can claim is that they desire the universe to be a certain way, and they live as if it actually is this way.

The Stoics do not derive their philosophy from Nature; they imbue Nature with their philosophy. They presume nature is rationally ordered, and then claim we should ‘align ourselves to nature’ by purging ourselves of all irrationality.

Not only is this belief in the order of the cosmos unjustified, Nietzsche thinks, but the Stoic view is also too quick in its dismissal of suffering. In his notebooks, he writes:

[Stoicism] underestimates the worth of pain […], the worth of excitation and passion.

While the Stoics seek to purge us of ‘irrational’ pain, Nietzsche thinks that once we strip away Stoicism’s optimistic teleology, suffering can be viewed as an authentic, understandable response to life in a world without order or purpose.

The way Nietzsche wants us to reconcile pain with amor fati is not by viewing suffering as a mistake that can be corrected, but by recognizing that it plays a necessary, indispensable role in a full life.

In fact, greatness is not possible without suffering. In The Gay Science, Nietzsche writes:

Examine the lives of the best and most fruitful people and peoples and ask yourselves whether a tree that is supposed to grow to a proud height can dispense with bad weather and storms; whether misfortune and external resistance, some kinds of hatred, jealousy, stubbornness, mistrust, hardness, avarice, and violence do not belong among the favorable conditions without which any great growth even of virtue is scarcely possible.

Reflecting on the role suffering has played in his own life, Nietzsche writes in Nietzsche contra Wagner:

As far as my long infirmity is concerned, isn’t it the case that I am unspeakably more indebted to it than I am to my health? I owe a higher health to it […] I owe my philosophy to it as well.

If there are things in our lives that we value, then Nietzsche wants us to realize that we cannot value those things without also valuing everything that brought them about. In his notebooks, he writes:

Suppose that we said yes to a single moment, then we have not only said yes to ourselves, but to the whole of existence. For nothing stands alone, either in ourselves or in things; and if our soul did but once vibrate and resound with a chord of happiness, then all of eternity was necessary to bring forth this one occurrence—and in this single moment when we said yes, all of eternity was embraced, redeemed, justified and affirmed.

Amor fati for Nietzsche thus means recognizing the interconnectedness of all. Happiness does not exist in isolation; greatness cannot occur without suffering. If we are to affirm life, we must affirm all of it — warts and all. In The Gay Science, he writes:

Only great pain is the ultimate liberator of the spirit…. I doubt that such pain makes us ‘better’; but I know that it makes us more profound.

Though not exactly enjoyable, suffering thus imbues us with a kind of tragic wisdom.

Perhaps the real measure of a person, Nietzsche goes on to suggest, is the amount of truth they can withstand. As we’ve seen him put it in Ecce Homo:

My formula for greatness in a human being is amor fati: that one wants nothing to be different, not forward, not backward, not in all eternity. Not merely bear what is necessary, still less conceal it… but love it.

Nietzsche develops these ideas further in his doctrine of the eternal recurrence, whereby he challenges us to live in such a way that we would wish to live the same life over and over again. Every heartbreak, every joy, every long day of boredom: in sequence, over and over again.

Only when we can say ‘yes’ to the eternal recurrence can we truly meet the challenge posed by Nietzsche’s amor fati.

Whose take on amor fati most resonates with you?

The Stoics advise us to practice amor fati because, ultimately, we are in the hands of rationally ordered Nature. We should exercise virtue in all that lies within our control, and purge ourselves of irrational feelings about all that lies outside of our control: this is how we conform to and affirm Nature’s teleological rational order.

Nietzsche, meanwhile, rejects the optimistic teleology of Stoicism. We must reconcile ourselves to necessity not by first imbuing it with meaning and purpose, but by facing it as it is, without such unjustified presumptions.

Nietzsche thus advises us to practice amor fati because, in the face of a Godless, purposeless, chaotic universe, it is the only valid response to nihilism: only by affirming the story of our own lives can we possibly bear existence. The onus is on us; it cannot be outsourced to teleology — life can only be justified and made worth living if we ourselves believe that it is.

As the scholar James A. Mollison aptly summarizes in his essay Nietzsche contra stoicism: naturalism and value, suffering and amor fati:

Whereas Stoicism creates a teleological order that must be submitted to at the expense of finding anything outside reason valuable, Nietzsche seeks to love fate without positing a pre-existing purpose or withdrawing from the world.

Whose take on amor fati do you prefer? Here are some further questions to consider:

- Do you think amor fati is a useful idea for living a good life?

- Does Stoicism’s rationally-ordered Nature or Nietzsche’s chaotic flux ring truer for you?

- Whose approach to reconciling ourselves to suffering do you prefer? The rationalization of the Stoics, or the ‘tragic wisdom’ of Nietzsche?

Learn more about Stoicism and Nietzsche

If you’re interested in learning more about Stoicism or Nietzsche, then consider checking out my related introductory guides: How to Live a Good Life (according to 7 of the world’s wisest philosophies, including Stoicism) and Introduction to Nietzsche (your myth-busting guide to Nietzsche and his 5 greatest ideas). You might also like the following related reads:

- Eternal Recurrence: What Did Nietzsche Really Mean?

- The Dichotomy of Control: a Stoic Device for a Tranquil Mind

- The Stoics on What to Do When the World Feels Broken

- Friedrich Nietzsche’s Life, Insanity, and Legacy

- Übermensch Explained: the Meaning of Nietzsche’s ‘Superman’

- Stoicism and Emotion: Don’t Repress Your Feelings, Reframe Them

- Aristotle vs the Stoics: What Does Happiness Require?

- The Apollonian and Dionysian: Nietzsche On Art and the Psyche

- Nietzsche On Why Suffering is Necessary for Greatness

- The Last Time Meditation: a Stoic Tool for Living in the Present

- Friedrich Nietzsche: the Best 9 Books to Read

- Stoicism: the Best 6 Books to Read

Finally, if you enjoyed this article, you might like my free Sunday breakdown. I distill one piece of wisdom from philosophy each week; you get the summary delivered straight to your email inbox, and are invited to share your view. Consider joining 25,000+ subscribers and signing up below:

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying my free Sunday Breakdown

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox.

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

About the Author

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (100+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Take Another Break

Each break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your philosophical curiosity.