The Apollonian and Dionysian: Nietzsche On Art and the Psyche

Since the time of Socrates, Nietzsche claims that Western culture has generally been too biased towards the ‘Apollonian’ (representing order and rationality) over the ‘Dionysian’ (chaos and vitality) — to the great detriment of art, truth, and the human psyche.

This article is a modified extract from my Introduction to Nietzsche guide, in which I distill Nietzsche’s most profound ideas.

When was the last time you lost your sense of self? Perhaps you were euphorically dancing in a crowd at a festival, or partaking in frenzied celebration for the victory of your favorite sports team. Maybe you were singing or chanting with a large group.

Or perhaps you’d simply taken a substance, be it alcohol or otherwise, that made you lose all your usual inhibitions and throw caution to the wind, the edges of your self-consciousness distorted into chaotic oblivion.

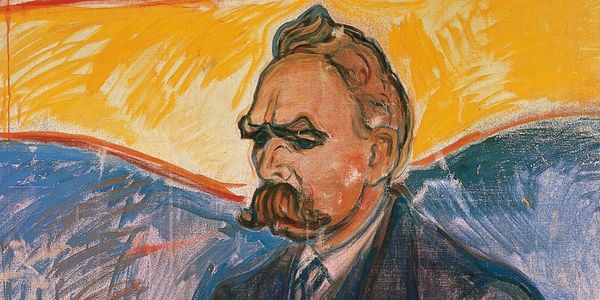

Whatever it was, when for those moments you let yourself go and became swept up in the ecstasy of the crowd or mob or self-dissolution, you were experiencing what 19th-century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche describes as Rausch, which is variously translated as intoxication, exhilaration, or frenzy.

In other words: losing all sense of self, unraveling into something unstructured, disordered, perhaps even liberating.

And then, of course — after the wild thrill of Rausch — you return to yourself. Plain old ordered consciousness, predictably (and individually) moving through structured time.

But, following Rausch, this refound sense of self is rocked slightly (and not just by the potential accompanying hangover), for we’ve had a taste of what Nietzsche dubs the Dionysian.

We’ve experienced an underlying chaotic reality that our bubble of individual consciousness usually separates us from.

Our structured sense of self (an expression of what Nietzsche labels the Apollonian) melted away to reveal an uncontrollable, unpredictable, pre-rational, selfless undercurrent: the Dionysian.

Nietzsche’s famous distinction between the Apollonian (representing our drive for order, harmony, and individuation) and the Dionysian (our contrary drive for intoxication, chaos, and deindividuation) has been hugely influential as a framework for interpreting art, the human psyche, and even the world itself.

Since the time of Socrates, Nietzsche laments, Western culture has generally been far too biased towards the Apollonian, championing rationality over vitality. Mocking those who hold such an attitude, he writes:

…[they] turn away from such phenomena as from “folk-diseases,” with contempt or pity born of the consciousness of their own “healthy mindedness.” But of course such poor wretches have no idea how corpselike and ghostly their so-called “Healthy-mindedness” looks when the glowing life of the Dionysian revelers roars past them.

Art, life, and philosophy are at their most fertile and vital and truthful, Nietzsche thinks, when they admit and make use of our Dionysian energy, rather than shunning it as unbecoming.

But what did Nietzsche really intend by making his distinction between the Apollonian and Dionysian? What do the two terms actually stand for? And how do they provide us with insight into the nature of art, truth, and the human condition?

The decline of culture

Nietzsche first distinguishes between the Apollonian and Dionysian in his 1872 work, The Birth of Tragedy, which sets out to show (among other things) that Western art and culture has been in decline since the time of the ancient Greeks.

With their epic tragedies, Nietzsche argues the ancient Greeks hit the apex of aesthetic creation, and managed to thus soothe the absurdity and pain of existence.

Nietzsche later criticized The Birth of Tragedy in his 1886 essay, An Attempt at Self-Criticism, admonishing it as

badly written, ponderous, embarrassing, image-mad and image-confused.

This essay now appears as the preface to most editions of The Birth of Tragedy, suggesting the later Nietzsche wanted to distance himself from his earlier work.

It should be noted, however, that as harsh as Nietzsche’s self-criticisms may seem, they were perhaps colored by the context as much as the content of his debut book, for The Birth of Tragedy was written at a time when Nietzsche was very close to Richard Wagner and the composer’s soon-to-be wife, Cosima.

The Wagners shared Nietzsche’s view about culture’s decline since the ancient Greeks, and The Birth of Tragedy was in some way Nietzsche’s attempt to provide a philosophical framework for this shared view — and to justify Wagner’s music as a return to form for humanity generally.

However, as I outline in my overview of Nietzsche’s life, insanity, and legacy, Nietzsche’s relationship with the Wagners soured dramatically in the years following the publication of Birth of Tragedy.

It is thus little wonder that the Nietzsche of 1886 wanted to distance himself from the work that Cosima described as the clearest expression of ‘Wagnerian’ thought.

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox:

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

Life is suffering

Before writing The Birth of Tragedy and making his famous distinction between the Apollonian and Dionysian, Nietzsche had engulfed and heartily concurred with the doctrine of the great German pessimist Arthur Schopenhauer: life is suffering.

Writing in the decades immediately preceding Nietzsche, Schopenhauer characterized human existence as involving an incessant and inherently painful ‘willing’.

Having read and agreed with much Indian philosophy (he especially admired Hindu text The Upanishads), Schopenhauer believed it was simply in our nature to always be straining towards some perceived deficiency.

Be those deficiencies survival-related (i.e. needing food and water), material (wanting a bigger house and nicer things), or existential (longing for meaning and fulfillment), we cannot help but yearn for things we don’t have.

According to Schopenhauer, our default mode of existence is thus to want — and to experience a want (i.e. being thirsty, hungry, anticipatory) is to suffer.

What’s more, even on obtaining our wants, satisfaction is fleeting and does not outweigh the pain the initial wanting caused in the first place, and a new want immediately replaces the old.

On balance, therefore, Schopenhauer concludes that life is suffering: the result of existence is pain.

As he puts it in his masterpiece The World as Will and Representation, if we were honest about the world, we would acknowledge that

it would be better for us not to exist at all.

The question, then, is why do we carry on?

Schopenhauer’s answer is that we are “tricked” by “the will to live” (one basic expression of which might be, for instance, the biological imperative to survive, whereby we instinctively avoid things that put our existence at risk).

We thus have an innate but ultimately irrational predisposition to exist: non-existence is in our best interest, but we deludedly (and subconsciously) deceive ourselves that this isn’t the case.

Our collective coping mechanisms

In The Birth of Tragedy, Nietzsche is largely in agreement with Schopenhauer’s pessimistic view, and in fact expands it to say that in order to deal with suffering and get through life, humanity has throughout its history come up with a number of collective coping mechanisms, or illusions. Nietzsche writes:

The insatiable will always finds a way to detain its creatures in life and compel them to live on, by means of an illusion spread over things.

One such illusion is what Nietzsche describes as “the Apollonian drive for beauty.”

Reaching back to the Homeric age of ancient Greece, Nietzsche claims this drive is what led to the

resplendent, dream-born figures of the Olympians.

Rationality is included in the Apollonian toolkit — and, rather strangely, Nietzsche claims another natural expression of the Apollonian is dreaming, because through our dreams we represent the world to ourselves with greater clarity and beauty. (To explain this and other unusual references to dreaming and control throughout his work, some scholars have suggested Nietzsche may have been a lucid dreamer).

The Homeric Greeks, meanwhile, expressed the Apollonian through their art. They captured all aspects of human life — even, as Nietzsche says, the “grave, gloomy, sad, and dark” aspects — and beautified them with heroic myths, dramatic sculpture, and epic poetry.

These artistic endeavors lent purpose to life and made its otherwise random events seem narrative-led and meaningful: the Greeks could dim or even justify the horror of existence by cultivating it as an aesthetic experience.

They composed their lives as spectacles for the gods, and thus gave meaning to otherwise senseless suffering and pain.

However, as successful as this Apollonian approach was during the Homeric age, it didn’t last long.

The Dionysian infiltration of the Apollonian

Nietzsche discusses the arrival of a cult of Bacchic revelers who follow not Apollo but Dionysus, the god of wine, fertility, and ritual madness.

In contrast to the Homeric Greeks, who escape the suffering of existence through the aesthetic devices of Apollonian dreaming (epic poetry, sculpture, heroic myths), the coping mechanism of choice for the Bacchic revelers is Dionysian intoxication (wild music, ritual madness, Rausch).

Nietzsche adapts the plot of the Euripides tragedy Bacchae to narrate how this cult of Bacchic revelers, with their terrifyingly primitive music and wild sexual abandon, tore apart the “artful edifice” of Apollonian culture, and revealed that the Homeric Greeks’...

entire existence, with all its beauty and moderation, rested on a hidden ground of suffering and knowledge.

Surrounded by such ecstacy, the Homeric Greeks were exposed to the untameable, pre-rational frenzy of the Dionysian.

And, as the philosopher Daniel Came puts it in his essay The Birth of Tragedy and Beyond (which features in The Oxford Handbook of Nietzsche),

Faced with the truth of the human condition, the Appolonian illusions could no longer suffice to protect them.

Indeed, following a night of Dionysian Rausch, the Apollonian Greek state of mind was permanently altered. Nietzsche writes:

[After] the ecstasy of the Dionysian state, abolishing the habitual barriers and boundaries of existence… they have understood, and action repels them; for their action can change nothing in the eternal essence of things, they consider it ludicrous or shameful that they should be expected to restore order to the chaotic world.

In other words, following an experience of Rausch, the Homeric Greeks saw the pursuit of Apollonian art as no longer enough.

Its individuation, order, and harmony — once a calming healing balm that lent purpose and meaning to life — had been punctured by the Bacchic cults of Dionysus to reveal the underlying chaos and deindividuation of existence.

As Nietzsche summarizes:

[Rausch] penetrates to the innermost thoughts of nature, it recognizes the fearful drive to exist and at the same time the perpetual death of everything that comes into existence… For a brief moment we really become the primal essence itself, and feel its unbounded lust for existence and delight in existence. Now we see the struggles, the torment, the destruction of phenomena as necessary, given the constant proliferation of forms of existence forcing and pushing their way into life, the exuberant fertility of the world will.

The question the Homeric Greeks thus had to answer: stripped of their aesthetic defenses, how could they possibly stand up to such fertile darkness?

Tragedy: the Apollonian and Dionysian combined

The Greeks were saved from nihilistic despair, Nietzsche declares, by inventing the art of tragedy. Tragedy has the power to transform

those repulsive thoughts about the terrible or absurd nature of existence into representations with which man can live.

In other words, tragedy combines both Apollonian and Dionysian drives: it beautifies yet faces up to the reality of the world.

The tragic hero struggles to make (Apollonian) order of the unjust and chaotic (Dionysian) circumstances they find themselves in: there is a fundamental mismatch between the hero’s needs and desires on the one hand, and the way the world actually is on the other.

As a medium, too, tragedy combines the epic poetry of the Apollonian with the music of the Dionysian: the Greek tragic chorus is for Nietzsche the classic expression of the Dionysian, for the performers act not individually, but narrate and pass comment on the play in unison, remaining eternally the same, regardless of what comes to pass with the progression of the narrative or of time itself.

Through tragedy, the Greeks — especially the works of Aeschylus and Sophocles, Nietzsche thinks — managed to symbolize (and thus distance and protect themselves from) the uncaring, timeless, deindividuated chaos of Dionysian reality.

The tragic hero has no rational control over circumstance or narrative, and through watching the events unfold the audience understands this represents the fate of us all. The Dionysian is thus filtered through the healing balm of the Apollonian, and becomes bearable.

By tempering — even affirming — the absurd, terrifying nature of existence in this way, the tragic worldview gets us closer to the truth of reality than any other artform or act of knowledge creation.

The highest art, the purest truth — and its downfall at the hands of Socrates

In The Birth of Tragedy, Nietzsche thus presents tragedy as the highest artform, the best way to deal with suffering, and the best characterization of existence.

For Nietzsche, the tragic worldview gets closer to the truth of reality even more so than the sciences, for the sciences fail to appreciate that anything humans do, any body of knowledge or art we create, is essentially a coping mechanism to deal with the bleak absurdity of existence.

The tradition of the Socratic pursuit of knowledge, for instance, suggests we become fully human by becoming fully rational.

This lesson, instigated by the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates (arguably the foundational figure in all Western philosophy), has been so deeply embedded into our psyches, Nietzsche argues, that we no longer question the value of pursuing truth in this way: we calmly reason about the world and believe all its mysteries will, ultimately, be explained with austere words and equations.

We delude ourselves into thinking that it is ‘truth’ we value, rather than merely pursuing it for something to distract ourselves from the yawning abyss of existence.

But by focusing only on detached rationality we lose a fundamental part of what it means to exist as a human being, Nietzsche thinks.

Specifically, we close ourselves off from the Dionysian, the pre-rational source of all of our greatest art and creativity.

Rejecting this fundamental part of ourselves leads to spiritual sickness and existential crisis. Socrates, in persuading us that the accumulation of knowledge is the only goal for humanity, simply started the rot. He made us emphasize our impulse for knowledge at the expense of all else, viewing it as not only useful but morally good to do so.

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox:

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

Under the influence of Socrates, the golden age of Greek tragedy thus morphed into the works of Euripedes, who used the Greek stage as a platform for morality and rationality, and Plato’s dialogues, where all human concerns are picked over with mere rational conversation.

We have inherited this world of cultural decline, Nietzsche thinks, where the primal power of the Dionysian is shunned, where knowledge is viewed as worth pursuing for its own sake, where the arts are denigrated as entertainment, where ‘reason’ feigns command, where the deep mystery of existence is subsumed by shallow rationality and science, and where spiritual sickness and existential crisis loom large.

But don’t worry: there is a solution at hand, Nietzsche advises.

Rescuing modern culture

By resurrecting the tragic worldview and allowing the Dionysian back in, by accepting and in fact celebrating the mystery of existence as something that may be greater than our rationality can comprehend — thus we can rescue modern culture.

As Neitzsche famously declares in The Birth of Tragedy,

it is only as an aesthetic phenomenon that existence and the world are eternally justified.

And, in fact, hope lies with the composer Richard Wagner, whose operatic tragedies light up the deepest caverns of the human psyche.

That The Birth of Tragedy concludes as such no doubt massaged the ego of Wagner, who could rest assured that he was restoring humanity to aesthetic glories not seen since the ancient Greeks.

But in Nietzsche’s later works, there is a suggestion that we can move beyond the tragic worldview to something even higher.

Indeed, while tragedy expresses the Dionysian, it is tempered by the illusions of the Apollonian. Some scholars argue that Nietzsche thinks we can transcend illusions altogether in dealing with life and instead embrace affirmation of the Dionysian itself.

For instance, Nietsche’s ideas of amor fati, the eternal recurrence, and the Übermensch involve confronting as much truth as we can about the horror of our existential situation and embracing it, rather than protecting ourselves with the healing balm of the Apollonian or other illusions like morality, religion, or the sciences.

We do not need to distract or delude ourselves from the terror of life, but rather find a way to affirm it despite or even because of its horror: embrace and take delight in all of life’s joys and all of life’s pains.

Facing up to reality

While Nietzsche’s distinction between the Apollonian and the Dionysian is a key theme in The Birth of Tragedy, it is never baked out explicitly either there or in his later works.

We might then wonder what the two terms are actually supposed to represent.

Are they aspects of the human psyche? Do they point to real ways in which Nietzsche thinks the world is structured? Are they just useful, productive concepts for investigating various artforms, attitudes, and approaches to life?

Scholars remain in lively discussion on these points. And, while following The Birth of Tragedy Nietzsche moves onto other projects and offers few clues, what we do see in his distinction between the Apollonian and Dionysian is a psychological depth that comes to characterize his later ideas.

Nietzsche recognizes that the problem is as Schopenhauer put it: life is suffering.

And the cultural history of humankind thus far — including all art, religion, and science — has been shaped by trying to respond to this suffering.

We distance ourselves from the truth of our existential situation by subscribing to these various belief systems or illusions, Nietzsche thinks. Subconsciously or consciously, we sign up to these collective coping mechanisms, for there is only so much truth we can withstand.

In his later works, Nietzsche goes on to express his view that humanity’s psychological development must involve the ability to withstand more truth — to in fact love and affirm our existential situation, rather than cover it in illusions.

The Birth of Tragedy’s influence

Nietzsche’s technique of looking for the root (and inspecting the development) of various concepts in human history is typical of his approach in later works, particularly in his sustained critique of morality in On the Genealogy of Morals, which I discuss in detail in my Introduction to Nietzsche guide.

Additionally, through his distinction between the Apollonian and the Dionysian, Nietzsche foreshadows his idea that the human psyche is constituted by various competing drives, which is the beginnings of his concept of the will to power, another point of discussion in my Introduction to Nietzsche guide.

What’s more, the distinction between the Apollonian and the Dionysian has been highly influential — for instance on Freud’s conception of the id and ego, as well as on the works of such thinkers as the anthropologist Ruth Benedict, who uses the terms to distinguish between different cultures.

So, while the later Nietzsche wanted to distance himself from much of what he wrote in The Birth of Tragedy, we can see that many of the ideas he is most famous for — including amor fati, the eternal recurrence, and the Übermensch — in fact had their germ in his earliest work.

The tantalizing distinction between the Apollonian and the Dionysian continues to fascinate, as does The Birth of Tragedy as a whole, despite Nietzsche’s later partial rejection of it — for what were arguably personal, rather than philosophical, reasons.

If nothing else, the Apollonian, Dionysian, and especially Rausch provide useful labels for areas otherwise lacking in colloquial terms.

Next time you lose yourself in the crowd, become part of something larger than you are, or let your sense of self dissolve... dwell on whether your loss of self actually gets you in touch with a deeper, deindividuated reality, whether your Apollonian consciousness is rocked the morning after the night before because your illusions — your everyday coping mechanisms — were shattered in the face of the beauty and horror of our existential situation... or perhaps because you were just very inebriated.

What do you make of Nietzsche’s distinction between the Apollonian and the Dionysian?

- Does your approach to life strike a healthy balance between the Apollonian and the Dionysian?

- Do you think we delude ourselves about the horror of our existential situation? Are our beliefs illusions? Is most of our activity a coping mechanism? Is there a limit to how much ‘truth’ we can actually withstand?

- Do you agree with Nietzsche’s assertion that tragedy is the highest (and most truthful) artform?

- Like art and religion, is science also a coping mechanism for dealing with the unknowability and suffering of existence?

- Is Nietzsche right to say existence can only be justified as an ‘aesthetic phenomenon’? What do you think he means by this?

- Is everyday consciousness itself an expression of the Apollonian, filtering and ordering an otherwise chaotic reality?

- Does Rausch actually get us closer to chaotic reality, or is the intoxicated Dionysian state also a useful illusion?

- What ‘illusions’ do you live by?

Learn more about Nietzsche’s philosophy

If you’re interested in learning more about Nietzsche, then consider exploring my popular self-paced Introduction to Nietzsche course (join 800+ active members inside).

You might also like the following related reads:

- Friedrich Nietzsche’s Life, Insanity, and Legacy

- God is Dead: Nietzsche’s Most Famous Statement Explained

- Eternal Recurrence: What Did Nietzsche Really Mean?

- Übermensch Explained: the Meaning of Nietzsche’s ‘Superman’

- Nietzsche On Why Suffering is Necessary for Greatness

- Amor Fati: the Stoics’ and Nietzsche’s Different Takes on Loving Fate

- Nietzsche On What ‘Finding Yourself’ Actually Means

- Friedrich Nietzsche: the Best 9 Books to Read

Finally, if you enjoyed this article, you might like my free Sunday breakdown. I distill one piece of wisdom from philosophy each week; you get the summary delivered straight to your email inbox, and are invited to share your view. Consider joining 25,000+ subscribers and signing up below:

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying my free Sunday Breakdown

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox.

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

About the Author

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (100+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Take Another Break

Each break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your philosophical curiosity.