Havi Carel on the Philosophy of Illness: Is Good Health Necessary for a Good Life?

After receiving a devastating diagnosis in her mid-thirties, the philosopher Havi Carel argues that, while society views ill people as objects of suffering, and medicine reduces them to sets of symptoms, those who are ill remain fully human and capable of happiness.

If you were informed you only had a few years to live, would that change how you approached your life? The philosopher Havi Carel received such devastating news in her mid-thirties. She’d noticed a new breathlessness when cycling to work, hiking with friends, and finishing her gym sessions. After various tests, she was initially told it was asthma; but the breathlessness kept getting worse.

Following more tests, Carel was diagnosed with an extremely rare lung condition (LAM) which, she was told, would steadily intensify. Her mobility would decline, she’d need to carry extra oxygen, and her death could be expected within ten years. No direct cause, no known cure; just sheer bad luck.

What does one do in such circumstances? How does one pick up the pieces?

All of us will experience illness at some point: many people already live with chronic or terminal conditions. Yet ‘good health’ is often assumed to be a key pillar of wellbeing.

If good health is taken away from you, does that mean you no longer have access to a good life? As we all inevitably decline with age, will we eventually be disbarred from happiness?

Carel investigates such questions in her brilliant and moving 2008 book, Illness: the Cry of the Flesh, in which she combines intimate first-person reflections on her condition with thoughtful philosophical analysis.

If someone receives a difficult diagnosis, Carel notes, adapting to the new reality is challenging enough, but it is made more so by two major societal obstacles.

The first is that medicine tends to reduce the ill person to a set of physical symptoms: the lived experience and reality of the person recede, as the management of biological functioning takes over.

The second is that wider society tends to view the life of the ill person only as tragic and full of suffering: people are fearful of illness, and so they tend to be fearful of ill people. Many disregard them entirely, or call them brave and move on.

The ill person, in addition to facing up to their illness, thus finds themselves socially alienated between these two conceptions of what they now are: a set of symptoms to be treated, and an object of suffering to be valorized or ignored. It is little wonder that illness can make people feel unseen, defeated, and alone.

Carel suggests both these societal obstacles can be tackled if we shed more light on the actual realities and lived experience of illness. Her route for doing so is phenomenology, a philosophical movement focused on the study of lived experience.

Healthcare rests on a lingering mind-body dualism; phenomenology can correct this and improve patient care

Carel thinks there lingers within the way we think and talk about healthcare a kind of mind-body dualism, inspired by Descartes: the body is a set of fleshy mechanics, distinct from the mind overseeing it.

Healthcare focuses on fixing the body, while the mind is expected to remain stoically aloof, transcendent, a praiseworthy spirit of courageous resistance. He continued fighting even as his body failed him.

Phenomenology can correct this kind of muddled thinking, Carel argues. Drawing on the existentialist philosophy of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Carel recommends a unified model of embodied consciousness where mind, body, and environment are inseparable. As Merleau-Ponty puts it in Phenomenology of Perception (emphasis added):

I do not bring together one by one the parts of my body; this translation and this unification are performed once and for all within me; they are my body itself … I am not in front of my body, I am in it, or rather I am it.

This unified experience is what Carel describes as the ‘lived’ body, which she distinguishes from the ‘biological’ body:

The biological body is the physical or material body, the body as object. The lived body is the first-person experience of the biological body. It is the body as lived by the person.

Medicine is concerned with the biological body. Its impersonal, third-person approach has been incredibly powerful in advancing the effectiveness of biological treatments. Carel is not calling for an end to this focus; she just suggests it’s augmented by an appreciation of the ‘lived’ body, too.

If disease is impersonal biological dysfunction, then illness is the personal, subjective experience of that dysfunction. The aim of healthcare should not simply be to cure disease but also to care for illness.

So what does medicine miss, exactly? What is the first-person experience of the lived body in illness?

Well, consider it in perfect conditions: when all’s going well, there is total harmony with the biological body. The biological body is ‘transparent’: we express ourselves with and through our bodies, without conscious thought.

But then something happens that makes us notice our bodies. We burn ourselves on the stove. We pull a muscle on the stairs. We feel a sore throat coming on. The body becomes a thing, a tangible object we attend to.

In other words: a rift forms between our biological bodies and our lived experience of those bodies.

Often these rifts are relatively short-lived. The burn heals, the muscle recovers, the sore throat clears up: the biological body recedes and transparency reigns once more.

Chronic illness, however, establishes the conditions for deeper and longer-term rifts. The biological body becomes perpetually present as a limiting object, altering the individual’s entire way of being. As Carel puts it:

Understanding this rift gives us the tools to describe the impact of illness… We can now begin to see how being ill is not just an objective constraint imposed on a biological body part, but a systematic shift in the way the body experiences, acts and reacts as a whole. The change in illness is not local but global, not external but strikes at the heart of subjectivity.

On this view, health can thus be understood not just as biological functioning but as feeling at home in one’s body; illness, meanwhile, involves estrangement from one’s body. This bodily alienation profoundly affects how someone interacts with and experiences the world. Their environment transforms into an “architecture of illness” where simple acts become “titanic” and freedom is compromised. Illness creates:

A new world... a world of limitation and fear: a slow, encumbered world... It is an encounter between a body limited by illness and an environment oblivious to such bodies.

Illness, then, is experienced from the inside not just as a range of physical symptoms but as a total reconstitution of existence. As Carel summarizes:

As embodied persons we experience illness primarily as a disruption of lived body rather than as a dysfunction of biological body. But medicine has traditionally focused on returning the biological body to normal functioning, and has therefore worked from within a problem focused, deficit perspective that ignores the lived body.

If we want to truly help those suffering with illness, the task is not simply to diagnose and monitor physical symptoms; the task is also to understand and care about how those symptoms are experienced ‘from the inside’.

Carel recognizes the passion and dedication of many of those in healthcare. Her point is more that medicine as a discipline is focused on biological functioning, and so the ‘bedside manner’ of those in healthcare depends on the natural human empathy and personality of the healthcare professional.

If medicine as a discipline were to be augmented with phenomenology, then perhaps how seen and heard a patient feels wouldn’t hinge so much on the individual personality of the healthcare professional. If our approach to healthcare incorporated first-person lived experience by default, we’d reduce the risk of patients feeling isolated or dehumanized.

Health, wellbeing, and growth within illness

While we shouldn’t overlook the profound impact of illness, we also shouldn’t underestimate the degree to which that impact, from the ill person’s perspective, becomes part of their everyday experience. Life must continue.

Viewed from the outside, chronic or terminal illness is a great calamity: people shrink from it and don’t know what to say. Carel recalls the friends she stopped hearing from, the strange looks and thoughtless comments her oxygen provoked in the street.

To make herself more socially palatable, she felt she had to hide her illness as much as she could. She played out faithfully the courageous role of the sufferer, putting on a brave face, allowing people to praise her strength and resilience:

First I am set up in a social context that forbids me from talking about my illness. Then, when I turn to other topics, I discover the social reward: I am seen as brave, graceful, a good sport. Didn’t she take it wonderfully, isn’t she coping just marvellously?

While the public imagination limits illness to persistent tragedy, presuming the reality of ill people is one of continual suffering, research offers a more mixed picture.

One study by Stuifbergen revealed that 60% of patients living with a chronic condition rated their overall health as good or excellent. Other surveys suggest self-reported wellbeing returns to pre-diagnosis levels within a year. Some even show experiencing illness can promote growth through awareness and transformational change.

The fact is: the experience of illness is richly varied, and its relationship to subjective feelings of ‘health’ and wellbeing is far from straightforward. A phenomenological approach can again help us here by demystifying the lived experience of illness.

Drawing on Heidegger, Carel notes that we can think about human existence as ‘being able to be’: we navigate the possibilities available to us, and these possibilities vary from person to person.

Illness may limit these possibilities, Carel observes, but “even within a contracted horizon of possibilities, there is still some choice.”

The limitations brought on by illness gradually become the normal background features of one’s everyday lived experience. Stephen Hawking wasn’t able to be a footballer, but he was able to become a brilliant physicist.

‘Othering’ ill people as tragic or heroic figures thus misses the point: all human beings face limited possibilities. As we age, all of us will have to come to terms with losing certain abilities: chronic illness simply accelerates this loss in some areas.

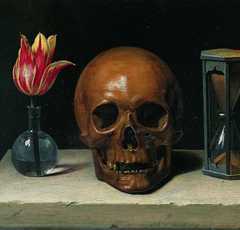

This acceleration isn’t exactly welcome, but it does bring with it awareness of life’s finitude. Such awareness has immense value: you are less likely to squander time if you are living with a keen sense of impermanence, Carel reflects:

People often talk about a capacity to understand the fragility and transience of life and nonetheless appreciate life’s goodness and value as a notable feature of illness.

Experiencing illness can thus bring rich insight and sagacity. In Phenomenology of Illness, Carel describes illness as a violent invitation for philosophical reflection. It forces one to dwell on the meaning of their life, values, and projects. It reconfigures their priorities.

This process is of course very challenging, very difficult, very painful; but it can foster a deeper appreciation of what matters. It can lead to what Nietzsche describes as a kind of ‘tragic wisdom’, or what the psychologist Jonathon Haidt calls post-traumatic growth.

Human beings are highly adaptable to adversity: we should never assume that suffering a calamity forever excludes someone, ourselves included, from picking up what remains and living a good life with it.

Finding happiness within illness

Carel’s diagnosis triggered an enormous and painful adjustment but it also taught her life lessons she might not have gained. Her illness cleansed her mind of many smaller anxieties: what’s the worst that could happen when the worst had already happened?

She discovered there were limits to her anger, sadness, and despair. She realized there were many different forms of catastrophe in people’s lives and hers was just one kind. Sources of pleasure and satisfaction remained available to her: some new ones opened up. She writes:

I thought about it like this: I have no control over this illness but I have full control over my emotions and inner state. I cannot choose to be healthy, but I can choose to enjoy the present, embrace the joyful aspects of my life and train myself to observe neutrally my sadness, envy, grief, fear and anger. The emotions washed over me. I observed them. By not fighting, by just letting them be, they became less mine, more tolerable.

Epicureanism suggests the good life consists in enjoying the tranquility that comes from fulfilling simple pleasures. This is one roadmap for happiness within illness, Carel suggests: working on one’s ability to adapt to new, more limited capacities, as well as finding satisfaction in the resilience and creativity that emerges in response to novel challenges.

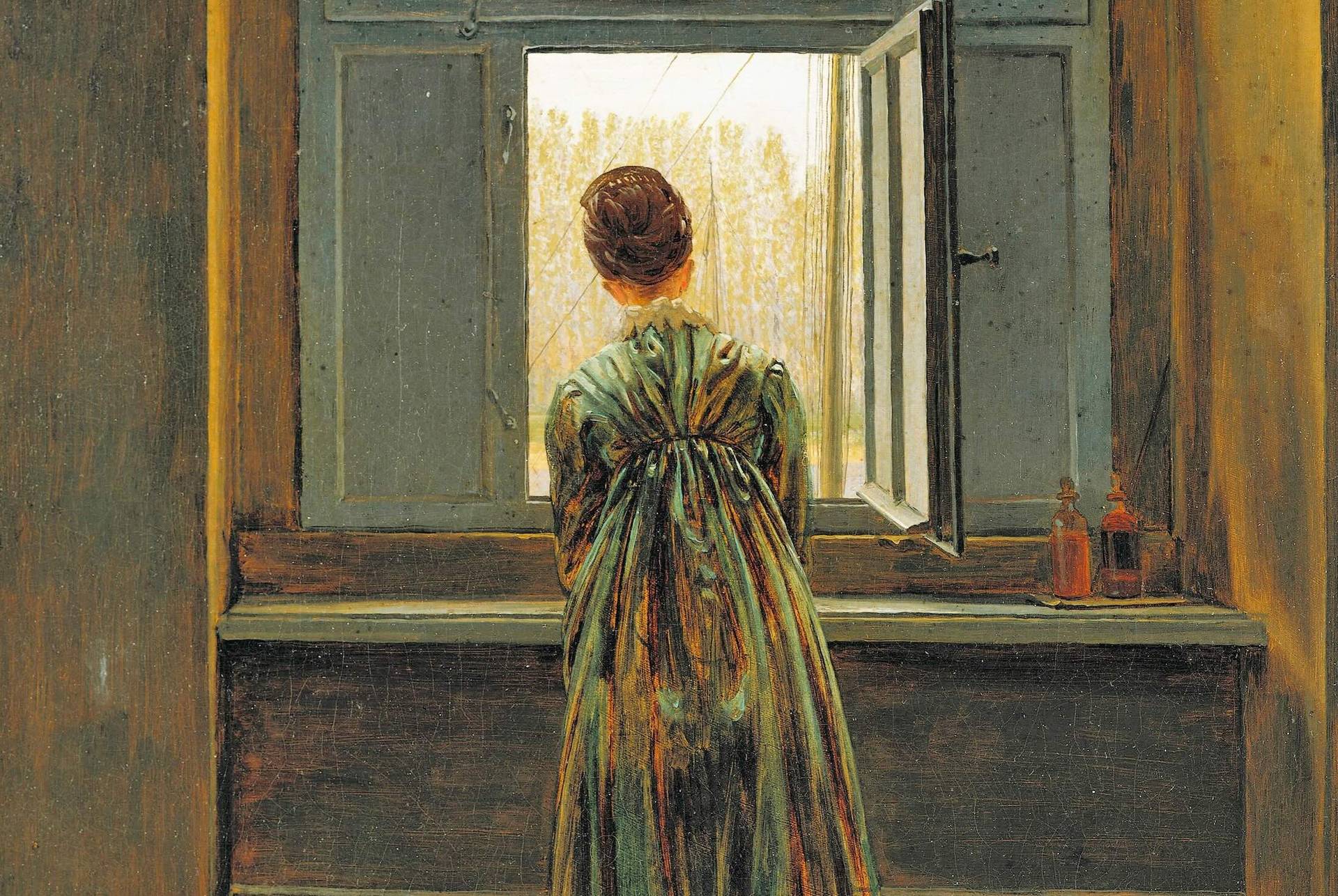

Not regretting lost abilities, not fretting over a lost future, but anchoring oneself to the present as much as possible:

Learning to live in the present with illness is learning to be happy now, regardless of threats to our future. It is learning to confine memories of past abilities and fears of the future so that they do not invade the present. It is learning to delimit them, stop them from shadowing the present. By changing our attitude to time, we can change the quality of the present, how much we enjoy living now.

This is a challenge to a style of living that values quantity over quality. What use are 80 years, if they are spent preoccupied?

Much better, surely, from our subjective first-person perspectives, to focus on learning how to enjoy the time we actually experience, no matter how much of it we have. As Carel writes:

And so I continue to ride my electric bike to work, go to yoga class and see friends and family. I continue to walk my dog, listen to music, write. I continue to live. Sometimes my illness makes life hard. It often takes up more time and space than I would like it to. But it has also given me an ability to be truly happy in the present, in being here and now.

Of course, not everyone will respond to illness in the way Carel has. Her point is just that illness does not disbar people from living a good life:

Happiness and a good life are possible even within the constraints of illness. But their uncovering requires a new set of conceptual tools (such as health within illness, adaptability) and a metaphysical framework that gives precedence to the experience of illness and to the embodied nature of human existence (phenomenology).

Carel challenges the preconceptions society has towards illness and wellbeing: illness should not be reduced to disease, and ill people should not be reduced to mere objects of suffering to be lauded or ignored.

Her work has been deeply influential in the philosophy of medicine, and she’s since worked with a number of organizations to incorporate phenomenology into medical training and healthcare.

In the foreword to the third edition of Illness: the Cry of the Flesh, Carel shares that she and a number of LAM sufferers were freed from the ten-year death sentence after responding to new treatment. She has since written about the extreme intensity of undergoing a double lung transplant. Thus she continues her brilliant and valuable work on the phenomenology of illness and wellbeing.

What do you make of Carel’s analysis?

- Have you experienced medicine’s focus on the ‘biological’ rather than ‘lived’ body?

- Is the concept of health captured by ‘biological functioning’? Or is someone’s experience of their biological functioning also important?

- If you were informed you only had a few years to live, would that change how you approached your life?

To inform your answers, you might enjoy the following related Philosophy Breaks:

- Epicureanism Defined: Philosophy is a Form of Therapy

- Michael Cholbi on Grief, Identity Crisis, and What We Learn from Loss

- Heidegger: We Are Time Unfolding (and our Time is Finite)

- Nietzsche On Why Suffering is Necessary for Greatness

- James Baldwin: Suffering Can Become a Force for Good

- Stoicism and Emotion: Don’t Repress Your Feelings, Reframe Them

- What is Existentialism? 3 Core Principles of Existentialist Philosophy

- Thich Nhat Hanh on Healing the Wounds of the Past

Get one famous philosophical idea in your inbox each Sunday

If you enjoyed this article, you might like my free Sunday breakdown. I distill one piece of wisdom from philosophy each week; you get the summary delivered straight to your email inbox, and are invited to share your view. Consider joining 25,000+ subscribers and signing up below:

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying my free Sunday Breakdown

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox.

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

About the Author

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (100+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Take Another Break

Each break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your philosophical curiosity.