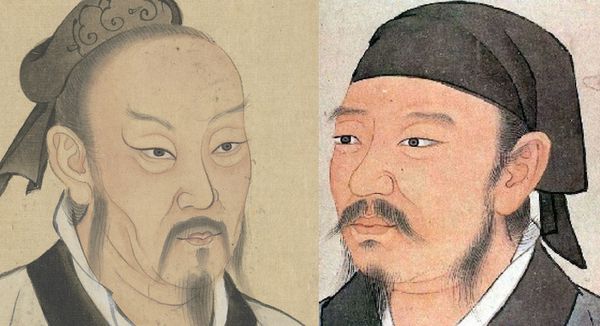

Mengzi vs. Xunzi On Human Nature: Are We Good or Evil?

The two ancient Confucian philosophers hold famously opposed views on human nature. Who do you agree with?

Though the tradition is named after him, Confucius is not the only prominent thinker of the ancient Chinese philosophy of Confucianism.

Mengzi (also known as Mencius, 372 - 289 BCE) and Xunzi (310 - 238 BCE) are the two other great Confucian thinkers from the ancient period.

And, while they are both rightly recognized as major Confucians, Mengzi and Xunzi actually fundamentally disagreed on a rather important issue: human nature.

The short and sweet summary is that while Mengzi thinks we are innately good-natured, Xunzi thinks we are profiteering rascals.

But a deeper look reveals a bit more nuance and complexity.

Mengzi on the sprouts of moral goodness

The first bond we form in life — that with our parents or primary caregivers — exposes what Mengzi calls our ‘sprouts’ of moral goodness.

These are our moral intuitions, or our predispositions for being good, compassionate human beings.

In a key passage from the Mengzi (a collection of dialogues featuring the great Confucian philosopher), Mengzi identifies four such sprouts, which are aligned to the key Confucian virtues:

- The sprout of ren (commonly translated as benevolence or humaneness, involving having a heart sensitive to the suffering of others)

- The sprout of righteousness (having a heart that feels shame or disdain in certain situations)

- The sprout of ritual proprietary (having a heart that feels courtesy or deference)

- The sprout of wisdom (having a heart that feels approval and disapproval and has a sense of right and wrong)

Mengzi says that “a person having these four sprouts is like their having four limbs,” continuing:

Having these four sprouts within oneself, if one knows to fill them all out, it will be like a fire starting up or a spring breaking through! If one can merely fill them all out, they will be sufficient to care for all within the Four Seas. If one merely fails to fill them out, they will be insufficient to serve one’s parents.

The ‘sprouts’ for goodness, then, are innate. As long as we are nurtured in healthy environments, Mengzi thinks, we are all capable of growing our sprouts into full-blown virtues.

Xunzi says: Mengzi is wrong

Xunzi calls out Mengzi directly in an essay rather candidly titled Human Nature is Bad, which features in Xunzi: The Complete Text. Xunzi writes:

Mengzi says: When people engage in learning, this manifests the goodness of their nature. I say: This is not so. This is a case of not attaining knowledge of people’s nature and of not inspecting clearly the division between people’s nature and their deliberate efforts.

For Xunzi, people have good moral characters because they have worked at them through their deliberate efforts.

Human nature is actually innately bad, Xunzi elaborates:

People’s nature is such that they are born with a fondness for profit in them. If they follow along with this, then struggle and contention will arise, and yielding and deference will perish therein. They are born with feelings of hate and dislike in them. If they follow along with these, then cruelty and villainy will arise, and loyalty and trustworthiness will perish therein. They are born with desires of the eyes and ears, a fondness for beautiful sights and sounds. If they follow along with these, then lasciviousness and chaos will arise, and ritual and righteousness, proper form and order, will perish therein.

For Xunzi, we have a love of profit and susceptibility to sensory desire that, if left unchecked, will lead us into personal suffering — and society into disarray.

Thankfully, on Xunzi’s view we also have an aptitude for intelligent, intentional action, and so by following the wisdom of the sages (the wisest among us), we can transform our innately bad natures into something good.

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying my free Sunday Breakdown

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox.

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

Mengzi emphasizes ren (benevolence), and Xunzi emphasizes li (ritual)

In his instructive essay Beyond Respecting Mencius and Criticizing Xunzi, the scholar Tao Liang positions Mengzi and Xunzi in relation to two key ideas of Confucianism, ren (commonly translated as benevolence or humaneness) and li (ritual).

Confucianism requires both ren and li, but Mengzi and Xunzi — following their views on human nature — each create a system that emphasizes one over the other, Liang observes.

Mengzi places emphasis on ren, whereby a sage can, as Mengzi puts it,

govern compassionately by following the compassion in his heart.

Goodness is our innate nature, Mengzi thinks: through reflection and learning, we must work on bringing our inherent virtues to the surface.

Xunzi, meanwhile, places emphasis on li: humans hold evil desires that must be transformed. Thanks to our intelligence, we are able to design rituals and collective social practices that improve us and create goodness.

So, unlike Mengzi, for Xunzi it is not a case of bringing our inherent virtues to the surface; rather it is a case of using our intelligence to transform our inherent natures into something good. As Liang expands:

By engaging in rituals and righteousness, the essential nature of man is transformed through artifice, and goodness is accumulated until it becomes virtue, and the country is governed through a system of rituals, Xunzi believed. This was the path to moral governance.

Confucius himself tried to reconcile ren and li, and by creating systems out of each, the work of Mengzi and Xunzi enriches the tradition, while also generating a bountiful philosophical tension at its center.

Mengzi and Xunzi: self-cultivation is paramount

Though their views on human nature are often seen as irreconcilable, and though they place emphasis differently on Confucian ideas, Mengzi and Xunzi are both simply highlighting the importance of moral development and the cultivation of our characters.

For Mengzi, becoming an exemplary person means nurturing our (innately positive) sprouts into fruition; for Xunzi, meanwhile, it means recognizing that our natures need shaping, just as…

crooked wood must await steaming and straightening on the shaping frame, and only then does it become straight. Blunt metal must await honing and grinding, and only then does it become sharp.

So, while their views on where we start from differ, Mengzi and Xunzi both champion the importance of cultivation.

For Mengzi, we require cultivation so that we don’t fall into evil; for Xunzi, we require cultivation to become good.

As the Confucian scholar David Wong points out, perhaps then the gap between the two Confucians isn’t so unbridgeable after all, for there is nuance in each of their positions.

Throughout his work, Mengzi notes the undesirable as well as good aspects of human nature; and Xunzi notes the positive feeling we get from acting well, and acknowledges our drive to be better, writing:

People desire to become good because their nature is bad.

The difference in outcome between someone fulfilling their innate goodness (Mengzi) and striving to better themselves (Xunzi) now looks relatively minor, we might think.

As Wong summarizes in his 2008 essay, Chinese Ethics:

Mengzi acknowledges that there are natural parts of the self that must be disciplined and held in check, while Xunzi acknowledges that there are natural parts that are largely congenial to morality in the sense that they are the natural basis for taking great satisfaction and contentment in virtue once one has gotten the self-aggrandizing desires and emotions under control.

Proceeding along the path of becoming an exemplary person, Mengzi and Xunzi thus agree, means placing great importance on the cultivation of our characters.

Our moral sprouts (be they positive or negative) simply signal our potential for development — and it’s our development that is most important.

So, while they disagree on our initial, innate human nature, Mengzi and Xunzi can be partially reconciled in their agreement that it is the cultivation of character, not its starting place, that matters most.

To answer the question of how we can then actually go about cultivating ourselves, Mengzi and Xunzi’s Confucianism takes over: while they place emphasis differently, they broadly agree that we develop ourselves morally by practicing filial piety, committing to study, mastering Confucian ritual behaviors, and engaging respectfully and compassionately with one another to form a virtuous, harmonious society.

Xunzi’s influence on Legalism

While Xunzi recommends the Confucian route of self-cultivation and ritual learning, his initial views on human nature — that we are naturally bad-natured — informed another important Chinese philosophical tradition, Legalism.

Xunzi’s insights into human nature aligned with and influenced those of important Legalist figures like Han Feizi and Li Si, who advocated for strict law and order as the only way to hold people in check.

This contrasts sharply with the Confucian mode of keeping people in line with virtue and ritual behavior.

Consider, for instance, Confucius’s famous statement in The Analects (which we discuss further in our explainer on the importance of ritual in Confucianism):

If you try to guide the common people with coercive regulations and keep them in line with punishments, the common people will become evasive and will have no sense of shame. If, however, you guide them with Virtue, and keep them in line by means of ritual, the people will have a sense of shame and will rectify themselves.

Learn more about Confucianism

If you’re interested in learning more about Confucian philosophy, we’ve assembled a list of the best introductory books on Confucianism here.

You may also be interested in our new guide, How to Live a Good Life (According to 7 of the World’s Wisest Philosophies), which compares the wisdom of Confucianism to six rival philosophies for life.

In the meantime — what do you make of Mengzi and Xunzi’s positions on human nature? Do you prefer Mengzi’s ‘sprouts’ to Xunzi’s ‘profiteering desires’? Are both of them right? Are both of them wrong? Or is their agreement over the importance of moral development more significant than their disagreement over its starting place?

How to Live a Good Life (According to 7 of the World’s Wisest Philosophies)

Explore and compare the wisdom of Stoicism, Existentialism, Buddhism and beyond to forever enrich your personal philosophy.

Get Instant Access★★★★★ (100+ reviews for our courses)

About the Author

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (100+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Take Another Break

Each break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your philosophical curiosity.