Nietzsche’s Perspectivism: What Does ‘Objective Truth’ Really Mean?

With his ‘perspectivism’, Nietzsche claims no one can ever escape their own perspective. It’s thus absurd to think of objectivity as ‘disinterested contemplation’. Knowledge comes not from denying our subjective viewpoints, but in evaluating the differences between them.

This article is a modified extract from my Introduction to Nietzsche guide, in which I distill Nietzsche’s most profound ideas.

Does objective truth exist? And, as mere biologically-limited humans, are we able to know anything about it? Philosophers have debated such questions for thousands of years, but the dominant view has generally been that a realm of objective truth — i.e. a single, universal reality — does exist.

Whether we can actually access this realm is another matter, but on this rather commonsensical view, objective truth exists independently of anything humans think or even could think about it. On the one hand, there’s the Truth, i.e. whatever is the case in reality; on the other, there’s us, trying to understand and form knowledge about it.

In Reason, Truth and History, the philosopher Hilary Putnam offers a good articulation of this position:

On this perspective, the world consists of some fixed totality of mind-independent objects. There is exactly one true and complete description of ‘the way the world is’. Truth involves some sort of correspondence relation between words of thought-signs and external things and sets of things.

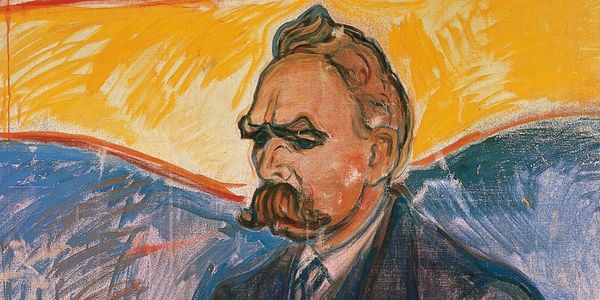

While this kind of ‘metaphysical realism’ pervades philosophy, science, and convention, in the 19th century along came Friedrich Nietzsche to spoil the party. “There are no facts,” Nietzsche declares in a famous aphorism, “only interpretations.”

Elsewhere, Nietzsche notes that “truths are illusions we have forgotten are illusions,” and that

truth is the kind of error without which a certain kind of being could not live.

So, what is Nietzsche saying here? Is he denying that objective truth — a true reality — exists? Is he implying that truth is relative? Would he endorse ancient Greek philosopher Protagoras’s famous provocation, that “man is the measure of all things”?

This is indeed what many postmodernist interpretations of Nietzsche claim.

Quotations like those above, removed from the context of Nietzsche’s wider thought, have associated Nietzsche’s name with the view that objective truth doesn’t exist: that ‘good’ and ‘bad’, ‘true’ and ‘false’ are all relative, dependent on external factors like culture, psychobiology, and environment.

Nietzsche’s name is thus often invoked by postmodernists to support their arguments: that appeals to ‘objectivity’ are always flawed, that all knowledge (and the world itself) is merely a conceptual construct with no guarantee of accuracy or relevance outside the narrow human experience, and that reason and logic themselves are valid only within the intellectual traditions in which they are used.

Such extreme relativism, critics retort, is dangerous, for it seems to undermine all sources of knowledge.

If truth doesn’t exist, how can we judge one view over another, if there is no objective standard about what’s right and wrong?

Why trust the opinion of a qualified doctor over someone who knows nothing about biology, chemistry, or medicine? Why put our faith in ‘experts’, if everything such experts learn and train for ultimately has no claim on truth?

How can Nietzsche answer such questions? Well, while there is perhaps good reason to see why his work inspired such postmodernist and relativistic views as those given above, scholars are generally in agreement that Nietzsche has more interesting things to say about truth than simply denying its possibility entirely.

Indeed, Nietzsche’s apparent outright denial of truth seems too blunt a view for so sharp a thinker.

Over the years, scholars have interpreted Nietzsche as providing a much more subtle, nuanced account of truth than some of his aphorisms might suggest.

This account has come to be known as Nietzsche’s perspectivism, and while there is still much disagreement as to what it actually entails, there is some common ground with which we can set the scene…

Our perspectives are inescapable

In his 1886 work Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche notes how, historically, philosophers have failed to take into account their own motivations and perspectives when articulating their views on the world.

Such thinkers claim ‘objective’ knowledge, or disinterested speculation, but really they’re bringing their own baggage to their proposed theories.

Nietzsche declares that “every great philosophy so far” — for instance, that of Plato and Kant — has been

the personal confession of its author and a kind of involuntary and unconscious memoir.

In another passage in his 1887 follow up, On the Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche writes:

[L]et us guard ourselves better from now on... against the dangerous old conceptual fabrication that posited a ‘pure, will-less, painless, timeless subject of knowledge’; let us guard ourselves against the tentacles of such contradictory concepts as ‘pure reason,’ ‘absolute spirituality,’ ‘knowledge in itself.’

Knowledge can never be ‘pure’, Nietzsche thinks, for no creature is capable of escaping its own perspective: no being can ever stand outside its own cognitive capabilities and interests.

As Nietzsche puts it in an early essay, On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense,

the insect or the bird perceives an entirely different world from the one that human beings do, and the question as to which one of these perceptions of the world is the more correct is quite meaningless, for this would have to be decided by the standard of correct perception, which means by a standard which is not available.

However, though Nietzsche thinks past philosophers have failed in their attempts to escape their own perspectives, he does not find their work unuseful.

In a key passage in his 1887 work On the Genealogy of Morality, he reveals how ‘objectivity’ might be achieved after all:

Particularly as knowers, let us not be ungrateful toward such resolute reversals of the familiar perspectives and valuations with which the spirit has raged against itself all too long… to see differently in this way for once, to want to see differently, is no small discipline and preparation of the intellect for its future ‘objectivity’—the latter understood not as ‘disinterested contemplation’ (which is a non-concept and absurdity), but rather as the capacity to have one’s Pro and Contra in one’s power, and to shift them in and out, so that one knows how to make precisely the difference in perspectives and affective interpretations useful for knowledge.

This famous passage highlights Nietzsche’s blunt rejection of objective knowledge as conceived as a ‘view from nowhere’ — i.e. as a form of objectivity that transcends all subjective appearances to reveal how things really are.

As R. Lanier Anderson puts it, Nietzsche suggests that

knowledge from no point of view is as incoherent a notion as seeing from no particular vantage point.

For example, if you look at a building, you are looking at it from a particular perspective.

In fact, you cannot see the building at all unless you look at it from a particular perspective (imagine it now: any view you have of, say, the Eiffel Tower, occurs from a certain angle; no ‘general’, ‘neutral’, or God’s eye view is available).

Your perspective thus makes possible your view of the building. So too with truth, Nietzsche seems to suggest: we cannot contemplate truth without doing so from a particular perspective.

Past thinkers who claim to have established ‘objective’ truth are thus simply espousing what seems true from their own vantage points.

This doesn’t necessarily render such vantage points erroneous, however, and indeed Nietzsche suggests that by combining or having mastery of different perspectives we can make progress with knowledge (the more angles from which we view the Eiffel Tower, for instance, the more complete will our knowledge of its appearance be).

In other words, perspectival knowledge is inevitable — we all have different interests and points of view, and our experience of the world is in fact made possible by these cognitive abilities and interests — but by acknowledging this and playing perspectives against each other, we can make progress.

As Nietzsche continues his passage:

There is only a perspectival seeing, only a perspectival ‘knowing’; and the more affects we allow to speak about a matter, the more eyes, different eyes, we know how to bring to bear on one and the same matter, that much more complete will our ‘concept’ of this matter, our ‘objectivity’ be.

Now, while this passage could be interpreted as simply suggesting that the more interpretations there are the better, it’s important to note that this doesn’t mean different interpretations necessarily carry the same weight. Some interpretations might be wrong.

For instance, if you have multiple maps of a certain territory — some containing geographical information, others demographic, others ecological — then combining these maps would provide more “complete” information about the territory. But that doesn’t necessarily mean every map is accurate.

As the philosopher Brian Leiter comments in his book, Nietzsche on Morality:

Perspectivism, construed thus, emphasizes that knowledge is always interested (and thus partial) and that differing interests will increase the breadth of knowledge, but it does not imply that knowledge lacks objectivity or that there is no truth about the matters known.

We might then wonder by what standard we can judge one perspective as being better than another.

Scholars disagree with how to deal with this tension in Nietzsche’s thought, but one approach is to take Nietzsche’s advice: that whoever can bring “more eyes, different eyes” to bear on a particular matter will have a more “complete” picture of it.

In other words, someone aware of their perspectival limitations, someone who is able to consider something from multiple points of view, “to have one’s Pro and Contra in one’s power, and to shift them in and out”, has a richer and thus more informed perspective than someone who only looks at things in one particular way.

Another way to defuse the tension in Nietzsche’s thought is to simply deny that it is much of a problem.

Standards exist within different fields — good science vs. bad science, good art vs. bad art — so it is relatively uncontroversial to think that, even without Nietzsche’s explicit, sustained guidance, we are capable of separating informed perspectives from ignorant ones.

Is knowledge determined by psychobiology?

Another point of contention between scholars is the extent to which Nietzsche suggests our access to truth is shaped not just by our individual cognitive abilities and interests, but by our psychobiological motivations, by what Nietzsche calls our ‘drives’.

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox:

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

In her book Nietzsche On Truth and Philosophy, for instance, Maudemarie Clark suggests Nietzsche’s perspectivism is primarily a comment on epistemology, the nature of knowledge.

For Clark, it amounts to the claim that the universe has no purely ‘Objective’ character. There is no general view of the universe that can be taken, for creatures from hawks to human beings all have different cognitive abilities and interests. The subjective, perspectival character of knowledge, then, cannot deprive us of anything we could reasonably want.

There are truths among humans, perhaps even truths shared by all beings in the universe, but such truths are never disinterested or purely Objective, for they are contextually dependent on (and only relevant to) various compatible cognitions.

For instance, it is a fact from the point of view of our best and most objective science that the Earth goes round the Sun. But science investigates the world it’s possible for human beings to comprehend. The world it’s possible for human beings to comprehend is not necessarily all there is.

Suppose there are beings who do not experience the universe in three dimensions — maybe they see it in two dimensions, or nine. Suppose there are beings who do not experience time in a linear fashion like we do. Such beings would likely have a totally different science to us. Maybe to them it would make no sense to say the Earth goes round the Sun.

The point of perspectivism, interpreted thus, is that all of our ‘objective truths’ must be qualified with ‘from the human perspective’, even if it that seems unnecessarily pedantic. We experience the cosmos in a particular way, so our truths are true only for that way of experiencing the cosmos.

2+2=4 is true for beings who have notions of number and addition; it is irrelevant for anything that doesn’t. As Clark writes:

Perspectivism amounts to the claim that we cannot and need not justify our beliefs by paring them down to a set of unquestionable beliefs all rational beings must share. This means that all justification is contextual, dependent on other beliefs held unchallengeable for the moment, but themselves capable of only a similarly contextual justification.

On this view, Nietzsche thus broadly rejects the possibility of metaphysics i.e. a disinterested — independent of the human perspective — fundamental theory of all there is.

Ken Gemes, however, in his 2013 essay Life’s Perspectives (which features in The Oxford Handbook of Nietzsche), argues Nietzsche is not interested in making a comment on truth or epistemology at all. His perspectivism might have consequences for truth or epistemology, but it should be viewed primarily as a psychobiological claim.

Indeed, Gemes connects perspectivism to Nietzsche’s will to power doctrine, whereby each ‘drive’ or ‘motivation’ within us has its own perspective of the world, and seeks to express that interpretation at the expense of other drives.

Perspectivism, Gemes thus argues, is a natural consequence of Nietzsche’s will to power doctrine.

On this latter view, it means — in stark contrast to Clark’s reading — Nietzsche does not dismiss the possibility of metaphysics with his perspectivism, but actually offers one himself: the world is a multiplicity of perspectives, vying for domination.

Where does Nietzsche’s perspectivism leave us?

The disagreement and confusion that surrounds Nietzsche’s views on truth is not helped by the fact Nietzsche himself seems to change his mind throughout his works.

In his early essay On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense, Nietzsche’s denial of truth is most apparent, and it’s this essay that’s responsible for driving the more postmodernist interpretations of Nietzsche’s views.

However, in his later works, particularly from On the Genealogy of Morality onwards, Nietzsche is a lot more enthusiastic on the possibility of truth, and indeed of science being our most effective method for obtaining it.

Of course, in these works he continues to critique science in terms of its ability to provide us with instructive value about how we should approach life — and that the pursuit of science at the expense of all else is psychologically damaging — but he no longer has as much of a problem with it as a vehicle for providing reliable and valuable knowledge about the what of existence (even though knowing more about the ‘what’ of existence doesn’t exactly help us cope with it).

There is another reason for doubting the popular postmodernist interpretation of Nietzsche, i.e., that he dismisses objective truth.

Indeed, if Nietzsche dismisses the possibility of truth, then presumably this means his own arguments fall into the ‘not true’ category.

This not only throws up the problem of self-reference (i.e. is the principle ‘There is no such thing as objective truth’ an exception to its own rule?), but also casts doubt on all of Nietzsche’s positive philosophy.

Why does Nietzsche bother, for instance, to characterize our experience of the world as an interplay between the Apollonian and the Dionysian in The Birth of Tragedy, if he does not think this observation actually coheres with the way things are?

Why does he bother formulating and telling us about his ideas like the eternal recurrence and the Übermensch or superman, if again he does not see at least some general truth in them?

Different levels of truth

Perhaps one way of resolving this apparent tension in Nietzsche’s thought is to establish different tiers of the word ‘true’ — Truth with a capital ‘T’, signifying a deep, disinterested, metaphysical Truth, and truth with a small ‘t’, signifying a general truth shared among compatible perspectives (but claiming no ‘objective’ reach beyond this).

There is no disinterested free-floating realm of objective Truth, Nietzsche thinks; there is only the world we subjectively experience — and we can experience and increase our knowledge about it only because of our perspectives, our cognitive abilities and interests.

A world without perspective — just like an object without a subject — is nonsensical. Disinterested contemplation of metaphysical Truth, Nietzsche thinks, is thus an absurd impossibility; affected discussion of what is true for us, held to established standards among various compatible perspectives, is all we can seek or realistically hope for.

So, we might say, Nietzsche does not consider his philosophy (or scientific knowledge) True in the metaphysical sense (for such Truth is impossible), but true in the “this is the best theory we currently have available from our limited human perspectives” sense.

Regardless of where we fall in these various readings, Nietzsche’s perspectivism is often lauded as one of his most philosophically valuable contributions in that it opened up a discussion around the extent to which external factors impact the ‘purity’ of knowledge.

It adds a subtlety and sophistication, a psychological depth, that was otherwise lacking when it comes to analyzing our theories of knowledge: we cannot escape our own perspectives, and so being conscious of what shapes and limits those perspectives is imperative for progressing knowledge.

In other words, the claims of philosophers and past thinkers need not only to be analyzed from the point of view of truth, but can also be diagnosed as symptoms of particular modes of being, and can be traced back to the complex configurations of psychology, drive, and affect from the point of view of which they make sense.

As R. Lanier Anderson summarizes:

Nietzsche’s perspectivism thus connects to his ‘genealogical’ program of criticizing philosophical theories by exposing the psychological needs they satisfy; perspectivism serves both to motivate the program, and to provide it with methodological guidance.

What do you make of Nietzsche’s perspectivism?

- Is there a True way the world really is? If so, which is more true, the world a dog sees, or the world a human sees?

- If there is no ultimate standard to which we can hold various perspectives on the world, how can we establish which perspective is more accurate?

- Do you agree with Nietzsche that the idea of a disinterested ‘view from nowhere’ is an absurdity?

- Is Nietzsche’s comparison between ‘seeing’ and ‘knowing’ valid? I.e. is he right to say that stripping perspective from knowledge is just as incoherent a notion as stripping point of view from seeing?

- What counts as ‘perspective’? Is it cognitive interests? Sensory capabilities? Psychological drives and motivations? All of the above?

- Is the postmodernist interpretation of Nietzsche viable?

- Does Nietzsche’s perspectivism contribute towards our understanding of existence?

- Does truth exist independently of thought?

- Is truth possible without language?

Learn more about Nietzsche’s philosophy

If you’re interested in learning more about Nietzsche, then consider exploring my popular self-paced Introduction to Nietzsche course (join 500+ active members inside).

You might also like the following related reads:

- Friedrich Nietzsche’s Life, Insanity, and Legacy

- The Apollonian and Dionysian: Nietzsche On Art and the Psyche

- God is Dead: Nietzsche’s Most Famous Statement Explained

- Eternal Recurrence: What Did Nietzsche Really Mean?

- Übermensch Explained: the Meaning of Nietzsche’s ‘Superman’

- Nietzsche On Why Suffering is Necessary for Greatness

- Amor Fati: the Stoics’ and Nietzsche’s Different Takes on Loving Fate

- Nietzsche On What ‘Finding Yourself’ Actually Means

- Friedrich Nietzsche: the Best 9 Books to Read

Finally, if you enjoyed this article, you might like my free Sunday breakdown. I distill one piece of wisdom from philosophy each week; you get the summary delivered straight to your email inbox, and are invited to share your view. Consider joining 25,000+ subscribers and signing up below:

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying my free Sunday Breakdown

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox.

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

About the Author

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (100+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Take Another Break

Each break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your philosophical curiosity.