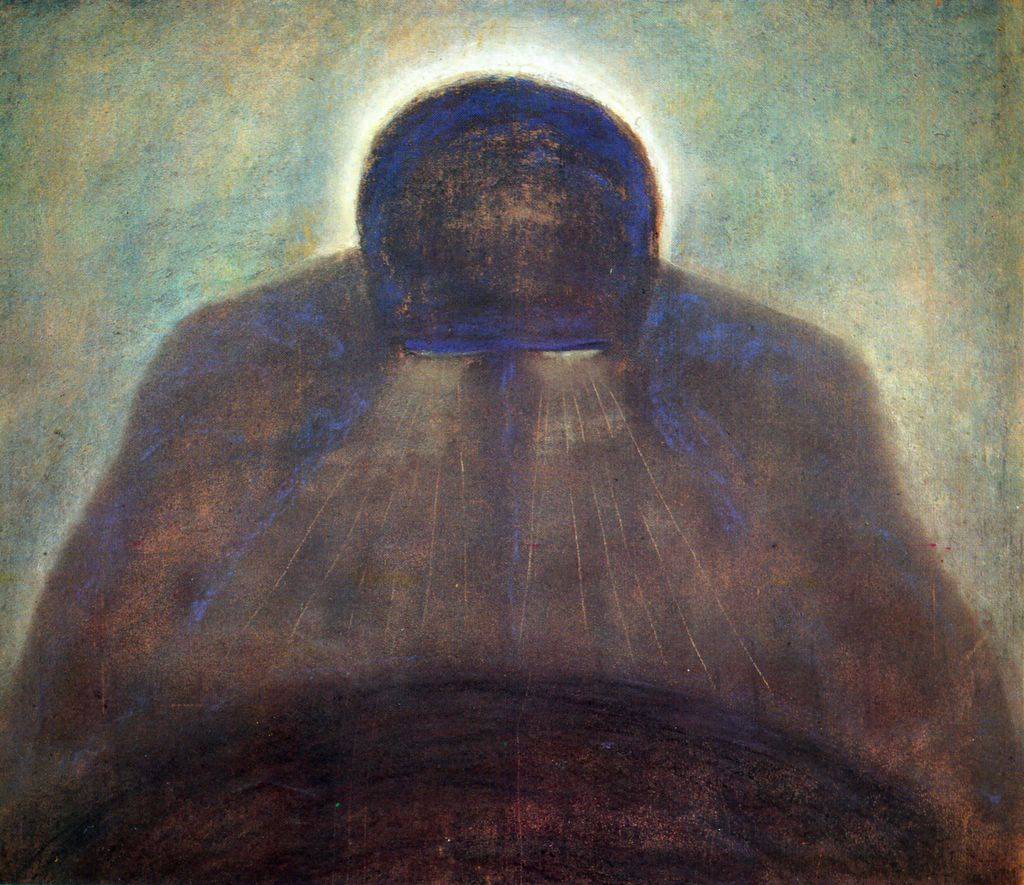

Kierkegaard: Life Can Only Be Understood Backwards, But It Must Be Lived Forwards

That we can only understand things in retrospect perhaps tells us something important about how to better approach life.

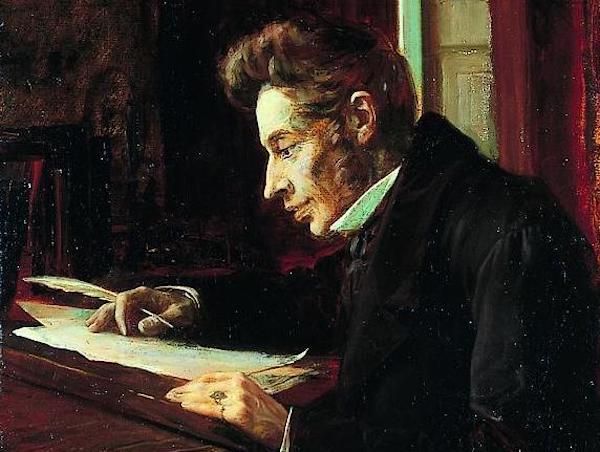

Søren Kierkegaard (1813 - 1855) was a Danish philosopher whose rich and varied writings have had a profound influence on philosophy, theology, and literature.

Kierkegaard articulates the anxiety, self-consciousness, and fraughtness of daily human existence in often exquisite prose — and it’s this laser focus on what it’s like under our own skin that cemented his reputation as a literary genius, and so inspired the existentialists of the 20th century. (See my reading list of Kierkegaard’s best books here.)

One feature of the human condition that Kierkegaard homes in on is that we move through time in one direction.

Consequently, we do not know what the future holds, nor the impact our choices will have.

Our understanding of events can occur only after we have experienced them. As a statement commonly attributed to Kierkegaard has it:

Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.

This statement is actually a shortened version of one of Kierkegaard’s journal entries. And, while it might seem a quite innocuous observation, its consequences on our psychological wellbeing are actually rather profound.

These consequences become clearer when we consider Kierkegaard’s fuller journal passage:

It is really true what philosophy tells us, that life must be understood backwards. But with this, one forgets the second proposition, that it must be lived forwards. A proposition which, the more it is subjected to careful thought, the more it ends up concluding precisely that life at any given moment cannot really ever be fully understood; exactly because there is no single moment where time stops completely in order for me to take position [to do this]: going backwards.

We are constantly moving forward in time. At no point do we get breathing space to pause and understand reality; it continuously unfolds before us.

The present is a constant stream of becoming that, when we try to hold it in place with our clumsy descriptions, ideas, and concepts, slips through our fingers.

We are thus fated to forever live our lives, Kierkegaard tells us, with incomplete information and understanding.

No matter what we want to happen, we cannot ever know what will happen, nor hope to immediately grasp it when it does.

Our future lives may split into various possibilities in our imaginations, but we can only ever live one of them — and even the one we ‘choose’ is unlikely to go as planned.

As I discuss in 5 Existential Problems All Humans Share, Milan Kundera describes this feature of existence succinctly in his 1984 novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being, writing:

Human life occurs only once, and the reason we cannot determine which of our decisions are good and which bad is that in a given situation we can only make one decision; we are not granted a second, third or fourth life in which to compare various decisions.

Do we just have to put up with this lack of knowledge, and the anxiety it causes?

That we can only understand things in retrospect perhaps tells us something important about how to better approach life.

If we insist on continuously trying to plan and execute the best life possible, all we can do is try to keep our worries, uncertainties, and expectations at bay as we fall forwards towards an open, unknowable future.

But if we accept that we will always have incomplete information, then perhaps we might also see the futility of trying to plan and control everything that happens.

We might realize, as the Stoic philosopher Epictetus also points out with his dichotomy of control, that insisting on reality being a certain way will likely lead to disappointment.

A statement often described as a ‘Kierkegaardian slogan’ (though it doesn’t actually appear in his writings) can help shed some light here:

Life is not a problem to be solved, but a reality to be experienced.

We do not (and will never) have the information required to forever ‘fix’ our lives — so why approach them as problems that need to be solved at all?

No matter what we do, reality will continually unfold before us. We can fight against this with plans, schemes, narrative arcs; but reality won’t care — for, in-itself, it doesn’t have any problems to solve. Reality invincibly goes on.

Perhaps, then, we might adjust our perspectives accordingly: put our energy not into endless reflection whereby we ‘fix’ the past or ‘solve’ the future, but in aligning better with what the very structure of existence demands: experience the unfolding of reality now.

As contemporary philosopher Laurie Ann Paul advises when discussing ‘transformative experiences’, if we cannot know the ‘best’ path forward with a major life decision, it’s often because there isn’t a best path; there are simply different paths, which we’ll adapt to we live them.

All else being equal, rather than exhaust ourselves on yet more research, cost-benefit analyses, and guesses at our future happiness, the most rational approach is to opt for the path we’re more interested in discovering. Instead of ‘fixing’ the future, we focus on the value of revelation.

After all, life is here to be experienced. What kind of experiences appeal to you? Spending time with loved ones? Expressing your creativity? Feeling the sun on your face?

Perhaps working out how to structure our lives more around such nourishing experiences — making a commitment to really show up for and live in them — is the only real ‘plan’, the only real solution we need.

Learn more about Kierkegaard’s philosophy (and the existentialism it inspired)

What do you make of this analysis? Do you try to meticulously control the future? Or do you approach life as something to be experienced?

If you’d like to reflect more on these themes or Kierkegaard’s philosophy generally, you might be interested in the following related reads:

- Kierkegaard On Finding the Meaning of Life

- Søren Kierkegaard: The Best 6 Books to Read

- Laurie Ann Paul on How to Approach Transformative Decisions

- Ruth Chang on Making Difficult Life Decisions

- Existence Precedes Essence: What Sartre Really Meant

- Nietzsche On What ‘Finding Yourself’ Actually Means

- Sartre’s Waiter, ‘Bad Faith’, and the Harms of Inauthenticity

- Heidegger On Being Authentic in an Inauthentic World

- What is Existentialism? 3 Core Principles of Existentialist Philosophy

Finally, if you enjoyed this article, you might like my free Sunday email. I break down one piece of wisdom from philosophy each week, and invite you to share your view. Consider joining 20,000+ thinkers and signing up below (free forever, no spam, unsubscribe any time):

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 20,000+ subscribers enjoying my free Sunday Breakdown

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox.

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

About the Author

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 20,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (100+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Take Another Break

Each break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your philosophical curiosity.