The Paradox of Choice: Barry Schwartz on Why More is Less

Though we assume freedom of choice to be a good thing, psychologist Barry Schwartz suggests too much choice fills us with anxiety and regret, and could lead people to seek more direction and control from their political leaders.

A problem for people in poor societies is they don’t have enough choice; a problem for people in rich societies is they have too much.

So observed psychologist Barry Schwartz in his 2004 book, The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less.

Freedom of choice is usually assumed to be a good thing, but Schwartz’s work suggests this is only true up to a point.

Consider the relentless choice in online shopping, for example. Say you’re browsing for a new pair of jeans. If you don’t have a ‘trusted brand’ in mind to whittle down the literally thousands of options, where should you start? Do you opt for this fit, or that one? Is this particular stitching important, or do you prefer that kind of belt loop? Should we get this sustainable pair, or those mid-blue ones with the incredible pockets?

Every consumer category is like this, from entertainment and hospitality, to domestic appliances and electronics. We must spend our limited time navigating a seemingly limitless number of options.

Schwartz distinguishes two responses to this situation: we can be ‘Maximizers’ or ‘Satisficers’.

If we’re maximizers, we settle for nothing less than the best possible option. We’ll hunt and scrutinize information ruthlessly; we’ll temporarily become world-leading experts in whatever category we happen to be making a decision in. Dishwashers. Smartphones. Ground paprika. You name it. We’ll secure the best deal, even if it takes hours, days, weeks of research.

If we’re satisficers, meanwhile, we embrace ‘good enough’, and then move on, freeing our minds for other activities.

Most of us are likely to be maximizers in some categories and satisficers in others. But Schwartz found that maximizers tend to experience more regret across the board. Having explored and considered so many different options, they are haunted by uncertainty and missed opportunities.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Schwartz thus urges us to become satisficers across as many categories as possible.

This is not easy. One of the jobs of consumerism is to convince us that even the most minor domestic inconvenience is an unbelievably high stakes problem, and that the solution we pick defines who we are.

But we should try not to sweat the small stuff. Obviously we want to make good use of our resources, we want the best for ourselves and our loved ones. The trap, Schwartz warns, is obsessing so much over an elusive ‘correct’ answer to all the little decisions we face that bigger decisions drift, and we squander the value of our time.

Of course, all this is a problem of privilege. The luxury of too much choice would be bitterly laughable to someone living in poverty, a dictatorship, a warzone.

But that doesn’t change the fact that being immobilized and made anxious by choice remains an everyday problem faced by millions of people around the world.

It also puts a rather large question mark over where humanity’s global consumerist enterprise is eventually headed.

Do we just continue packing up freightships, warehouses, and shopfronts with a mass-produced variance of objects, many of which no one really wants, uses, or needs?

Exhausted freedom

Not only does an abundance of choice tend to make us less satisfied with the choices we do make, Schwartz suggests, it also leads to decision fatigue.

If we channel all our ‘freedom’ into relatively trivial decisions like which TV show to stream, which holiday to go on, which set of bed linen will maximize style and comfort, then we have less energy to face what actually makes a difference to our lives: who to love, how to be, what to stand for.

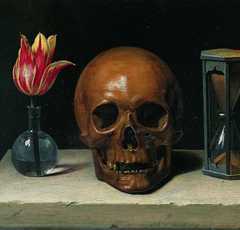

This is the caliber of choice existentialist philosophers wrote so much about. We truly define ourselves not through our toothbrushes but by facing the freedom we are ‘condemned’ to have: how to spend our one and only existence…

Today, however, Kierkegaard’s “anxiety is the dizziness of freedom” could just as aptly capture the experience of what it’s like to buy a toaster.

Yet if we feel bereft of control in navigating the bottomless pit of everyday consumerism, if we feel we often don’t have clear direction in our personal decisions, then imagine how we feel politically.

As Schwartz reflected in a recent interview with The New Philosopher: is it any wonder that as people increasingly lack power and certainty in their own lives, they seek more of both from their political leaders?

Ultimately, we mustn’t confuse endless consumer choice with genuine freedom. Instead, we might consider the kind of freedoms worth wanting — not as consumers, but as living, breathing human beings.

What do you make of Schwartz’s analysis?

- Do you recognize yourself as a ‘maximizer’ or a ‘satisficer’?

- Can there be such a thing as too much choice?

- Could choice have a ‘happy medium’? What would that look like?

- Which freedoms do you value?

To inform your answers, you might enjoy the following related Philosophy Breaks:

- Laurie Ann Paul on How to Approach Transformative Decisions

- Ruth Chang on Making Difficult Life Decisions

- Kierkegaard: Life Can Only Be Understood Backwards, But It Must Be Lived Forwards

- Heidegger On Being Authentic in an Inauthentic World

- Byung-Chul Han’s Burnout Society: Our Only Imperative is to Achieve

- Existence Precedes Essence: What Sartre Really Meant

- Hannah Arendt on the Human Condition: Productivity Will Replace Meaning

Get one famous philosophical idea in your inbox each Sunday

If you enjoyed this article, you might like my free Sunday breakdown. I distill one piece of wisdom from philosophy each week; you get the summary delivered straight to your email inbox, and are invited to share your view. Consider joining 25,000+ subscribers and signing up below:

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying my free Sunday Breakdown

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox.

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

About the Author

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 25,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (100+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Take Another Break

Each break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your philosophical curiosity.